It feels like the whole world is on fire. This is what people, especially young people, say when you ask them how they are. It’s an understandable response to climate change, increased international tensions and war across the world.

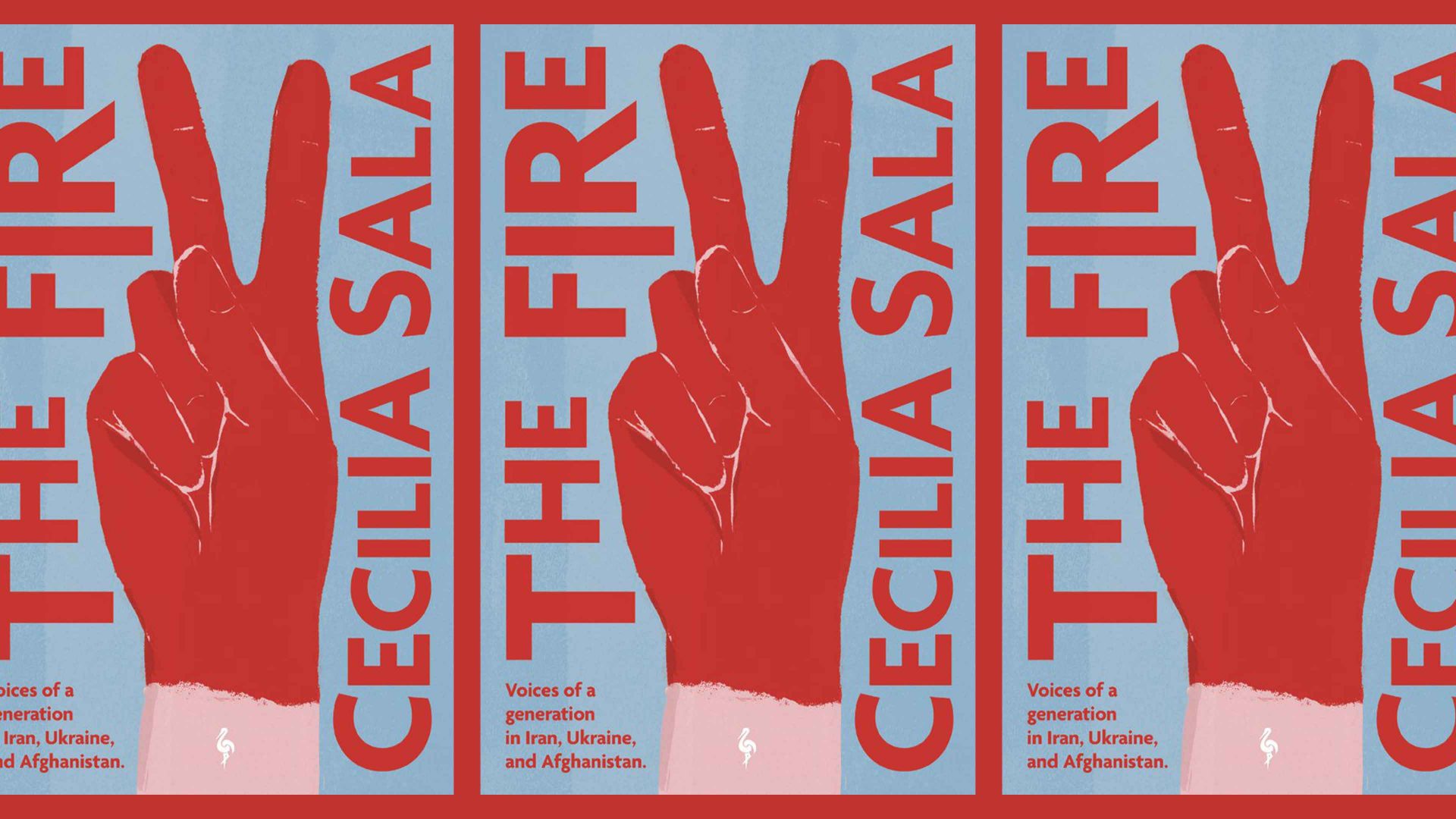

In The Fire, Italian journalist and war reporter Cecilia Sala wades into this fire to tell the story of a generation of young people dealing with a world alight around them. Their resistance is not their choice, it is something forced by circumstance. Sala visits three crucibles of war or armed uprising – Iran, Ukraine and Afghanistan. She traces the community organisation, armed resistance and the history of a violent struggle being carried out by a “golden generation” of young activists.

Like a modern-day Martha Gellhorn, Sala is intrepid, side-by-side with her peers, avoiding explosions in Mariupol, facing searches at Russian checkpoints and donning a full chador in order to pass unnoticed through the streets of Iran’s major cities.

Most of those she engages are deft users of social media and the internet: They do not need a journalist to tell their stories. What Sala offers is an experienced observer, one who weaves the threads of their personal narratives alongside those of global struggle more generally and the often complex geopolitics of particular regions. She does not give them voice, she gives them context.

In Iran, she tells the story of female resistance, the movement which arose following the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, and gained ground the following year becoming “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Kurdish for Woman, Life, Freedom). She charts its relationship to earlier and later movements and gives the reader a framework to understand what is happening in the country now.

Defined perhaps by a refusal to wear a veil, women’s bodies have been placed at the centre of these movements, because women’s bodies were placed centrally within the state’s modus of control. Men have been using their bodies too, placing them between their sisters and police bullets. The women’s struggle has become about much, much more.

Sala raves with revolutionaries, eats with them, parties with them. In a country where women are not allowed to dance or sing, the same people who run drugs and weapons organise raves interspersed with operas “to help out the frustrated sopranos in Iran.”

Suggested Reading

Edward Said and the war on intellectuals

For them, defiance is a culture and culture is defiance. They are the smiling dancers, rappers and singers currently lighting up social media with videos that are likely to land them in jail or hanging from a crane in the centre of the city they call home.

In Ukraine, she tells the stories of unsung heroes of war, ordinary people who turned informer on their Russian business associates, teenagers who trained with their grandparents in combat and battlefield techniques, the city residents who provide protesters and revolutionaries with borscht to keep their strength up.

She writes about the young software engineers who have created apps to allow every resident to interrupt Russian websites and internet operations from their sofas on a Sunday evening, and about Roman Ratushnyi, who spent his schooldays engaged in his own war with Russian interference and the Ukrainian oligarchs who enabled it before becoming an activist journalist.

Ratushnyi learned law, combat skills and in 2022, headed up his own brigade named after his neighbourhood back home. Then he was killed. Roman and his friends were part of a “golden generation”, an elderly lady tells Sala. She says that Putin’s greatest crime will be to have deprived Ukraine of its brightest and best.

For many of these young activists, events in Europe or America currently are baffling. To the young Ukrainians who risked their lives protesting to force politicians to let them join the EU, the idea that other countries would advocate leaving is inconceivable. In Ukraine, used to Russian interference, it is taken as read that Putin pulled the strings for Brexit.

The final section on Afghanistan lacks some of the first-person interviews and sense of voice of the others. Presumably because it is more difficult to find and talk to those willing to speak out. What it offers is a fascinating account of the fall of Afghanistan, the power-brokering which took place between the US and the Taliban, and the repercussions still being felt.

In this sense, it offers the context for the whole book – that we have always had far less democratic control than we imagined. While previous power grabs like in Kabul in 2021, Crimea in 2014 or Tehran in the 1970s, might have been dressed up as crucial foreign interventions to bring and strengthen democracy, they often ushered in systems which delivered authoritarianism, terror and war, enabling international capital to triumph at the expense of the people. Ruling nations might now be more bullish and blatant in intent, but they are not a million miles from their forebears in outcome.

The young revolutionaries of The Fire understand this. In countries which have always been subject to the whims of foreign power brokers, our illusions about our own democracy are quaint. Mark Carney’s hard truths come as no surprise to them.

The book offers a context and perhaps even a blueprint for struggle. A series of beacons which mark out how ordinary citizens gain agency in a world controlled by others. In these fiery times the stories provide crucial context and words of caution but also something else in short supply: hope.

The Fire by Cecilia Sala, translated by Oonagh Stransky, is published by Europa Editions.

Dr Katherine Cooper is a writer and literary historian