What better time to rediscover the work of one of America’s greatest thinkers than when its democracy is imperilled and the arts that she championed are bearing the brunt of Donald Trump’s cuts?

One of the 20th century’s most influential thinkers on race, gender and the arts, bell hooks stood at the intersections before Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term. These intersections – race, gender, class, sexuality – we now know, influence everything from our life expectancy to our access to art and culture.

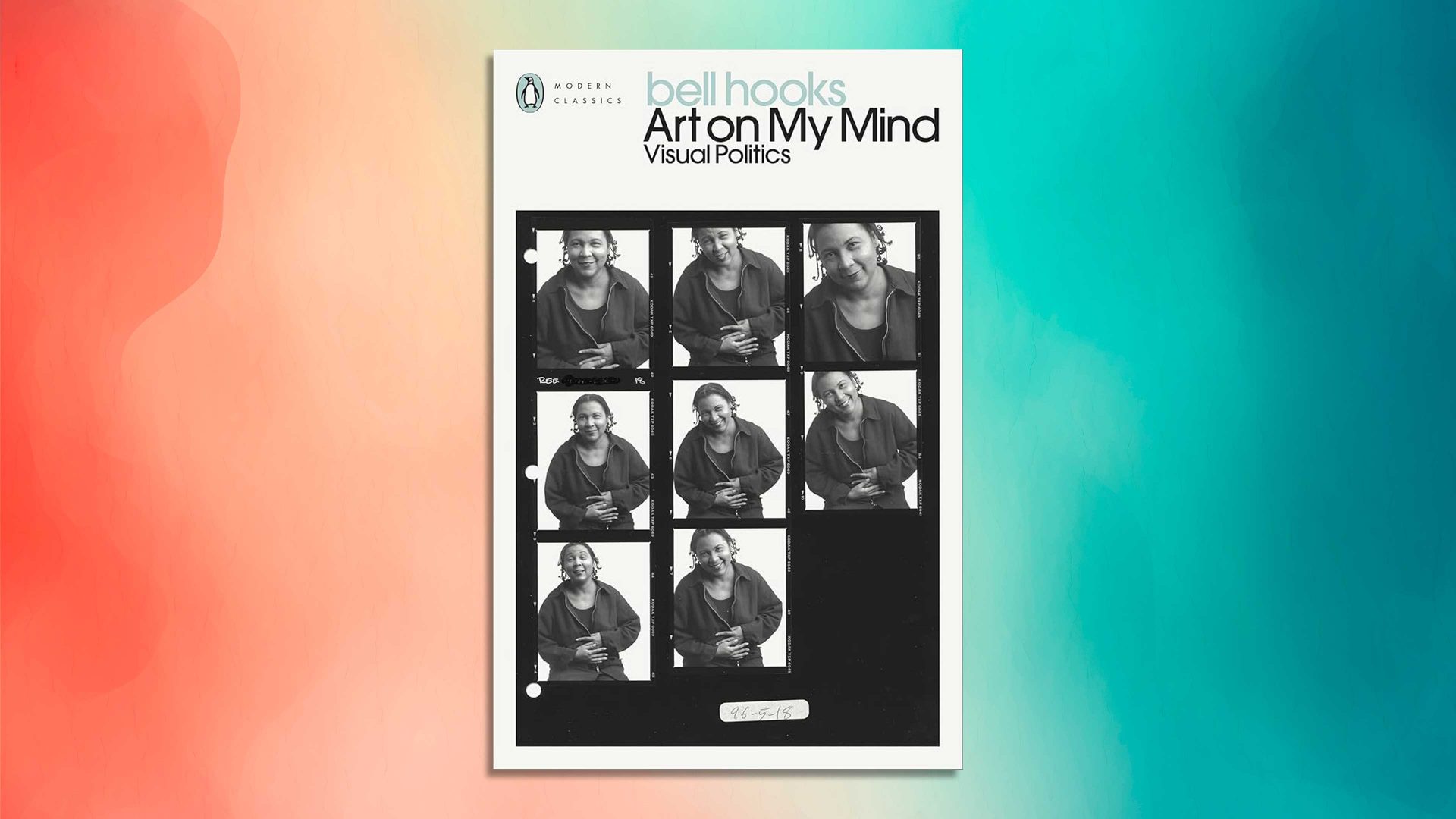

In the 1995 collection Art On My Mind: Visual Politics recently republished by Penguin, this Black feminist trailblazer walks the boundaries, exploring their impacts on the ways in which art is produced, presented and enjoyed within the African-American community. But her work stretches beyond analysis: hooks looks to art and culture and its appreciation as a radical, revolutionary process.

Her interviews with and engagements with Black artists and the power of art are about offering a corrective to a critical and cultural discourse around art that was (and remains) mostly white, but they are also just as much about self-realisation and political empowerment.

She interviews Black artists Alison Saar and Emma Amos and explores the legacy of 80s expressionist Jean-Michael Basquiat to consider what it means to be a Black artist operating within a largely white art world, in which work is appraised by white critics within a framework developed by white American and European thinkers over centuries. She considers sculpture and architecture, print-making and the creative process in search of a better way to discuss Black art and culture.

Work by Basquiat, she writes, “suggests that assimilation and participation in a bourgeois white paradigm can lead to a process of self-objectification that is just as de-humanising as any racist assault by white culture”.

hooks writes about her own encounters with African art in museums, admiring its daring, its exuberance, its expression. This does not tally, thinks her younger self, with what she has been told about “black folks and art”.

Suggested Reading

Nick Lowles, the fighter of hate who hid from the sun

“It occurred to me then that if one could make a people lose sight of their will and their power to make art, then the work of subjugation, of colonisation, is complete,” hooks writes.

What is revolutionary about hooks’s thinking is that it is both simple and powerful. Her concern in assembling this collection of essays arises from her feeling that, among other members of the Black community, her family, her friends, art was not considered important or relevant. It was a luxury, a place from which many of her peers felt excluded.

We can see this narrative still playing out in political culture across the world: art, music, languages are repeatedly figured as the province of elites. In such straitened times – we are told – ordinary people don’t need art, they need practical skills to make money. Art is extraneous, silly, playful.

What hooks notes astutely about this approach is that it (very deliberately) obfuscates the fact that art is powerful. It can comment on society in a myriad of ways, and holds a meaning that cannot be controlled by the powerful or the wealthy. Indeed, art is so powerful that when one invades a country, colonises a people or tries to erase a way of life, the most brutal and the earliest attacks are against artworks, artists, free expression.

Artists are the canaries in the coalmine. History shows quite clearly that if your artists are under threat, if the ability of writers to speak the truth is being challenged by the authorities, that’s when you are in trouble.

That, of course, is precisely what’s happening in the US and, to a lesser extent, other democracies now. Trump has eviscerated the National Endowment for the Arts, which funds the work of artists and community groups deploying art across a range of settings in the US, from care homes to playgroups, opera houses to galleries, community choirs to artists’ studios.

He has also taken a chainsaw to the National Endowment for the Humanities, which funds the work that records, analyses and supports this work in universities, libraries and museums. Art can now – much like in Stalin’s Russia – only be made and appreciated if it foregrounds the ideology of the republic, or glorifies its leader.

All of this makes a return to the work of one of America’s greatest thinkers even more timely.

Art On My Mind: Visual Politics by bell hooks is published by Penguin.

Dr Katherine Cooper is a writer, broadcaster and academic