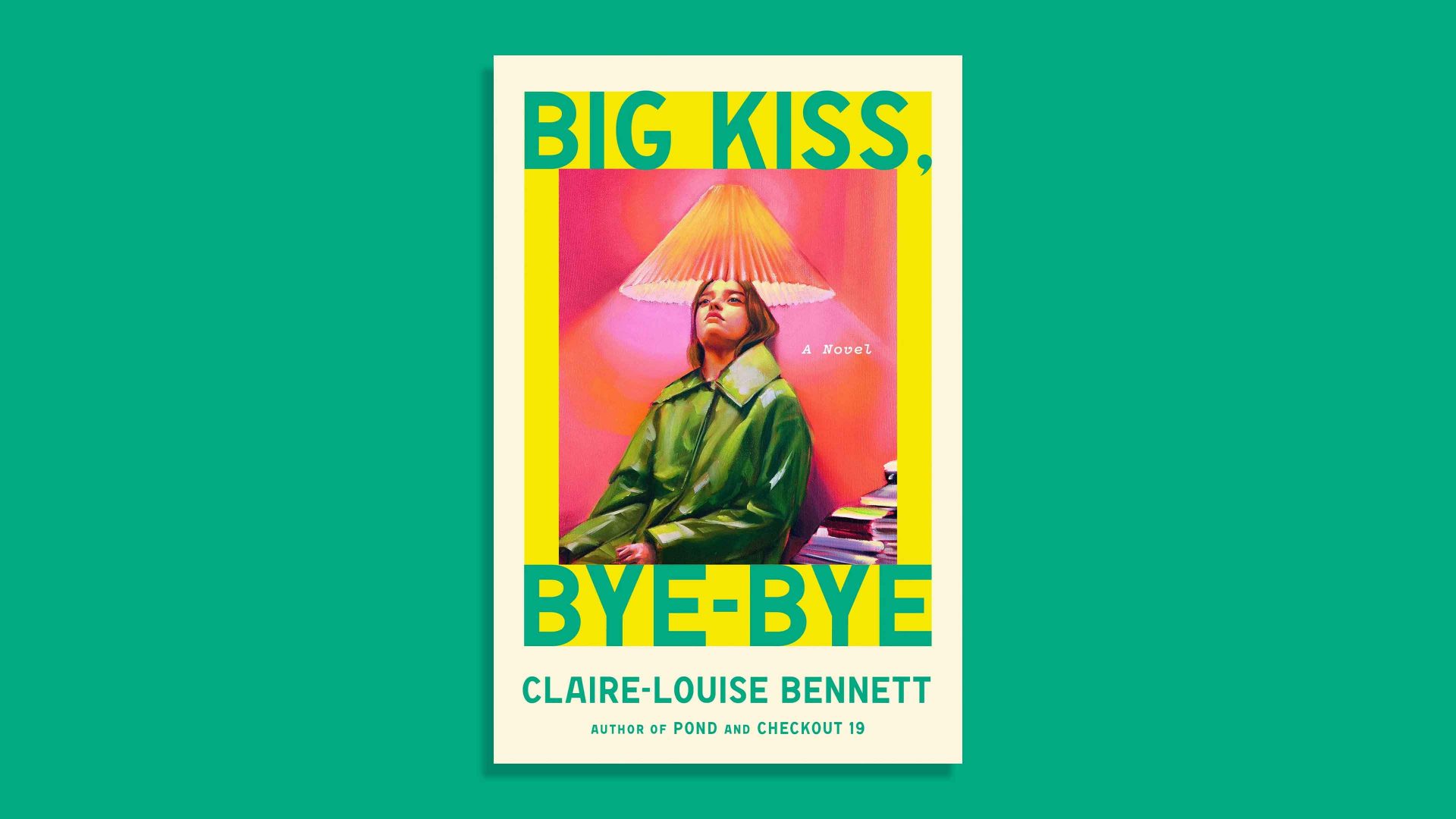

Claire Louise Bennett’s new novel Big Kiss, Bye-Bye marks a return to form, in every sense. Following the sizeable splash (sorry) made by her 2015 debut collection of interconnected short stories Pond and lukewarm 2021 novel Checkout 19, Big Kiss, Bye-Bye finds the avant-garde writer once again lingering over detail, rehashing and reimagining everyday events with her trademark joy.

The British-born Bennett now lives in Ireland and thus finds herself linked with the belated recognition of Irish women’s writing and with writers from Sally Rooney to Eimear McBride. Bennett does indeed share something of McBride’s dives into the minutiae of life and consciousness and certainly invites similar comparisons with the great Irish modernists of old, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

I imagine that for most Irish women writers, there’s nothing quite like a Joycean comparison to really take the shine off their success – invoking the great modernist totem to ward off any claims one might have to originality, experiment or self-expression. There’s no doubt that Joyce and Beckett have left their fingerprints across contemporary Irish fiction for the better, but Irish female novelists can claim a glittering heredity in their own right: The late, great Edna O’Brien, Kate O’Brien, Anne Enright, Marian Keyes, and even the subtly subversive Molly Keane.

Their wry, witty, lyrical, listenable prose, their voices, spill out at every corner of Irish women’s writing and if it has been having a huge explosive moment (it’s more than a decade now) then these names deserve credit too.

There has been much debate over the origins of this recent wave of successful Irish women writers. Their achievements have been variously attributed to the Celtic Tiger economy, Ireland’s increasing political progressiveness, and even the Good Friday Agreement. Ironically, it is only now that some truly outstanding work is receiving the recognition it deserves.

Suggested Reading

Reading is the new resistance

Rather than Joyce and Beckett or Rooney and McBride, Bennett owes more to her transatlantic sister from another mister, the poet Gertrude Stein. As becomes clear throughout her debut and – happily – this wending, tittering, meandering piece, her great gift is to pull out the details of life and particularly objects that are both alienating and immediately recognisable.

Stein’s own ode to detail, Tender Buttons (1914) is the backdrop to many an undergraduate fever dream, a book unfairly labelled “difficult” and “unwieldy” when in fact its bite-sized poems offer dreamy dips into the unrecognisability of everyday objects. Bennett too chronicles the edges, feels and fripperies of her surroundings.

In Pond, one of the standout moments comes from a description of her broken, knobless cooker, whose two-ringed lack of symmetry she corrects by propping “a mirror along the back edge of it so that now to all appearances it has four rings too, just like anyone else’s hob. People said the mirror would get hot and crack and of course the mirror got very hot and cracked but once the glass had cracked three times it didn’t crack again. Perhaps that was all the tension it had in it to be got rid of, because those three cracks occurred in quick succession right at the beginning and, as I’ve said, there’s been not a splinter since.”

In Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, it is also the small things that shine and chatter, conveying meaning and connection as well as familiarity. Bennett’s nameless female protagonist lives alone, has particular habits and interests which are repeated ad nauseum, takes and picks up, smooths and admires, tastes, smells, and sorts the objects, items and even the people in her life: “I wonder about those rare people who never move. Who live on and on in the same house. Never really needing to sort through anything. Never having to handle each and every object in turn. Never having to weigh up its value.”

In many ways, this is a book about picking things up and putting them down, with a particular emphasis on picking up relationships and putting them down again – big kiss, bye-bye. There is a unhurried beauty in the descriptions of these occasionally maudlin, occasionally joyous renderings of physical intimacy, sexual excitement and its demise. Not to mention the awkward process of extraction and flight: “Would I float diaphanously to his side, administer a reassuring kiss, a kiss he’d very likely interpret as an expression of gratitude, then twirl away and plonk myself down somewhere out of sight in order to write?”

As with Stein’s buttons, there is an otherworldly beauty, a revelling in the unnoticed and unremarked which is both thrilling and comforting. Bennett’s attentiveness to detail, to form, to cacophonous description and wordplay, is captivating. It is prose you can lose yourself (or someone else) in.

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye is published by Fitzcarraldo.

Katherine Cooper is a producer at the National Centre for Writing