Margaret Atwood smirks about her status as a modern oracle, lauded by the world as someone who sees the future. With a raised eyebrow, she insists that her stories are not of what will come but of what horrors man has already visited upon his fellows.

Surprisingly, she is a proficient palmist and astrologer, but during her public appearances she rolls her eyes and pronounces herself a sceptic about both. She does similar when asked about The Handmaid’s Tale, her prophecy of modern America: casts her sharp eyes around and goes for a laugh.

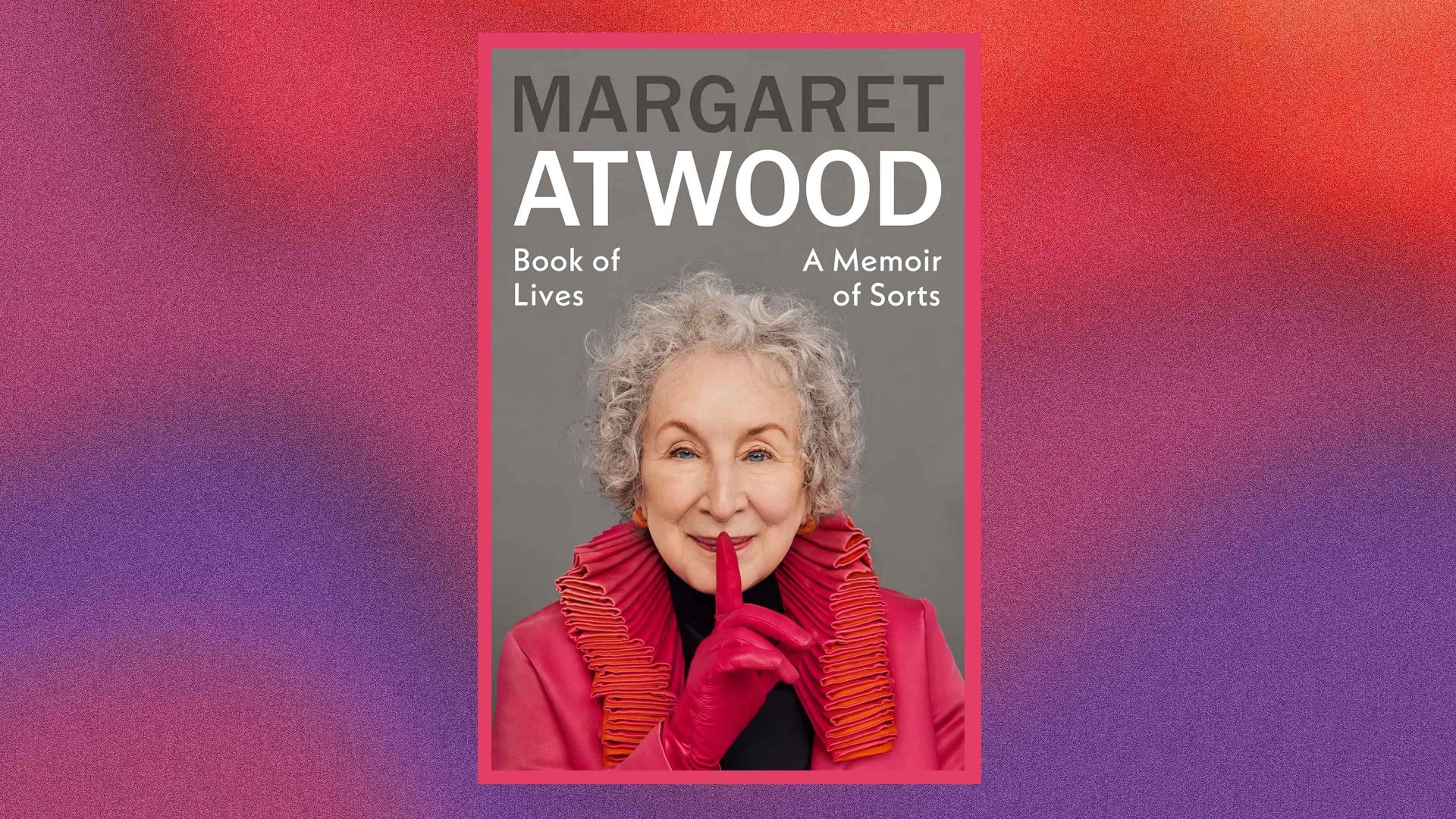

Her memoir, Book of Lives, moves with this same ready wit, the same glint. Her publishers have been begging her for a memoir for years. She has finally produced it, a weaving together of her many lives and the many experiences, people and places which have brought her to this exact spot, at 86, one of the world’s most-lauded authors. Soothsaying be damned.

The book is filled with stories, anecdotes, people, from her inspiring countryman father who built houses for the family and huts in the woods, who taught all of his children to fish, boat and sail, her incredibly game, wise mother, who once saw off a bear with a broom. Siblings, cousins, friends, enemies, frenemies…

Her memoir is not short of scores settled, with childhood bullies, literary rivals and disloyal friends coming in for the usual caustic loquaciousness: “if you stand at the same bend in the river for a long time, you will eventually see the bodies of your enemies float past”, she observes gleefully. She is full of such elegant and macabre one-liners.

She embodies a very female phenomenon of having to inhabit a number of different bodies at different parts of her existence – hence the titular “lives”: child, playwright, confidant, provocateur, flirt, virgin, tom-boy, homemaker, cleaner, cook, mother, novelist, poet. The latter feels like her first and her most central self.

Her poetry is her great gift. Once you try the poetry you’ll never go back. She reveals the joy of her first collection and her bemusement at the hostility generated among older poets when it won the prestigious Governor General’s Award for The Circle Game in 1964, at the time the only literary accolade available in Canada. Her regular collections since then have best given voice to her two selves, Margaret and Margaret the writer, whom she views as a darker doppelgänger operating in the shadows and the unconscious. The poetry allows for this play between self and creativity without the pressures for a successful novelist to keep churning out the hits (try Paper Boat, 2024).

Suggested Reading

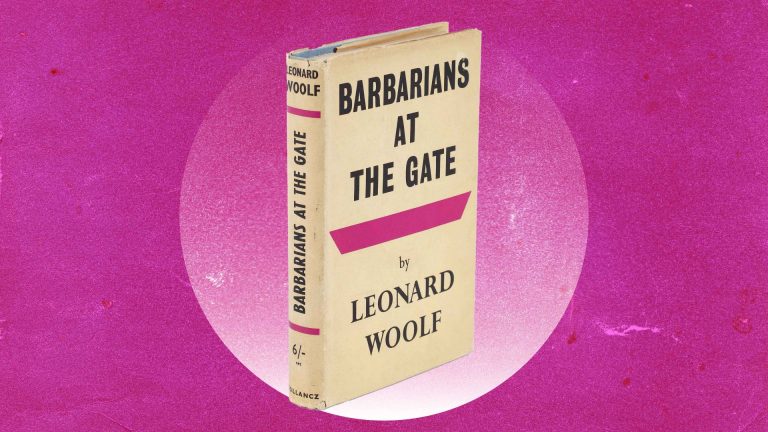

The book from 1939 that reads like breaking news

The Handmaid’s Tale is always just out of view throughout much of the book, presumably at the request of the publishers, mindful of an audience hungry always for more insight. Atwood has spoken many times to the roots of this book which are at least partly in her experiences as a female PhD student at Harvard in the 1960s: The division of men and women, the strange rites behind closed doors, the policing of women’s clothes, the reluctance to admit women to libraries and research rooms despite their presence as students. The great-and-good of Harvard have apparently made their peace with this now and entertain her presence there, but for some time, they did not.

This patriarchal thin skin remains elsewhere. Despite its huge success as a TV show, Atwood’s most famous book is now one of America’s most banned. Not, as is claimed, because of the scenes of rape it depicts but because it stands as a mirror to an increasingly authoritarian US of tradwives, the erosion of reproductive rights and the gradual grinding down of hard-won women’s rights. Like an ugly stepmother, America does not like what it sees.

Atwood is eye-rollingly familiar with book-banning after serving for decades as a leading figure in Canadian PEN and PEN International – she even took a blowtorch to a flame-proof copy of The Handmaid’s Tale as part of the promotion of its prequel, The Testaments, published in 2019. PEN (Poets, Essayists and Novelists) is the international organisation that campaigns for writers’ rights and free expression worldwide. Atwood and her husband, the novelist Graeme Gibson, worked tirelessly for Canadian PEN, raising money for writers in prison and organising events and such. But it was not all hard, serious work. They also organised skits and revues and even musicals during the 1980s and 1990s.

During one of their skits, in which Atwood is on stage in full costume performing a montage of country songs but with a literary slant (including Ghost Writers in the Sky) they paused to introduce Salman Rushdie. Rushdie had not been seen since the fatwa and had been smuggled into Canada by the head of Canadian PEN, Louise Dennys. Rapturous applause followed from the gathered writers.

In this and countless other events at the intersection of the personal and notable world events, the book convenes with the spirits of the future and the past. A great many of Atwood’s contemporaries are dead, along with Gibson, an absence which occasionally chills her buoyant chirpiness.

Nevertheless, like her female characters she resists, maintaining an infectious energy and sharpness. The book is a masterclass in voice, her crackling wisecracks reach out of its pages, her snipes and sniggers are infectious.

She is a writer very much at her peak, which brings me to a word of warning (very Atwoodian): A good many people will be treating this as her last word. They haven’t read carefully enough to apprehend her shapeshifting endurance: I’m certain she’s set for a transformation or two before she’s done.

Dr Katherine Cooper is a writer and literary historian