An old woman lies on her deathbed in the depths of the forest. Around her, others prepare for a peaceful end to a life spent wrestling for power with forces beyond her control.

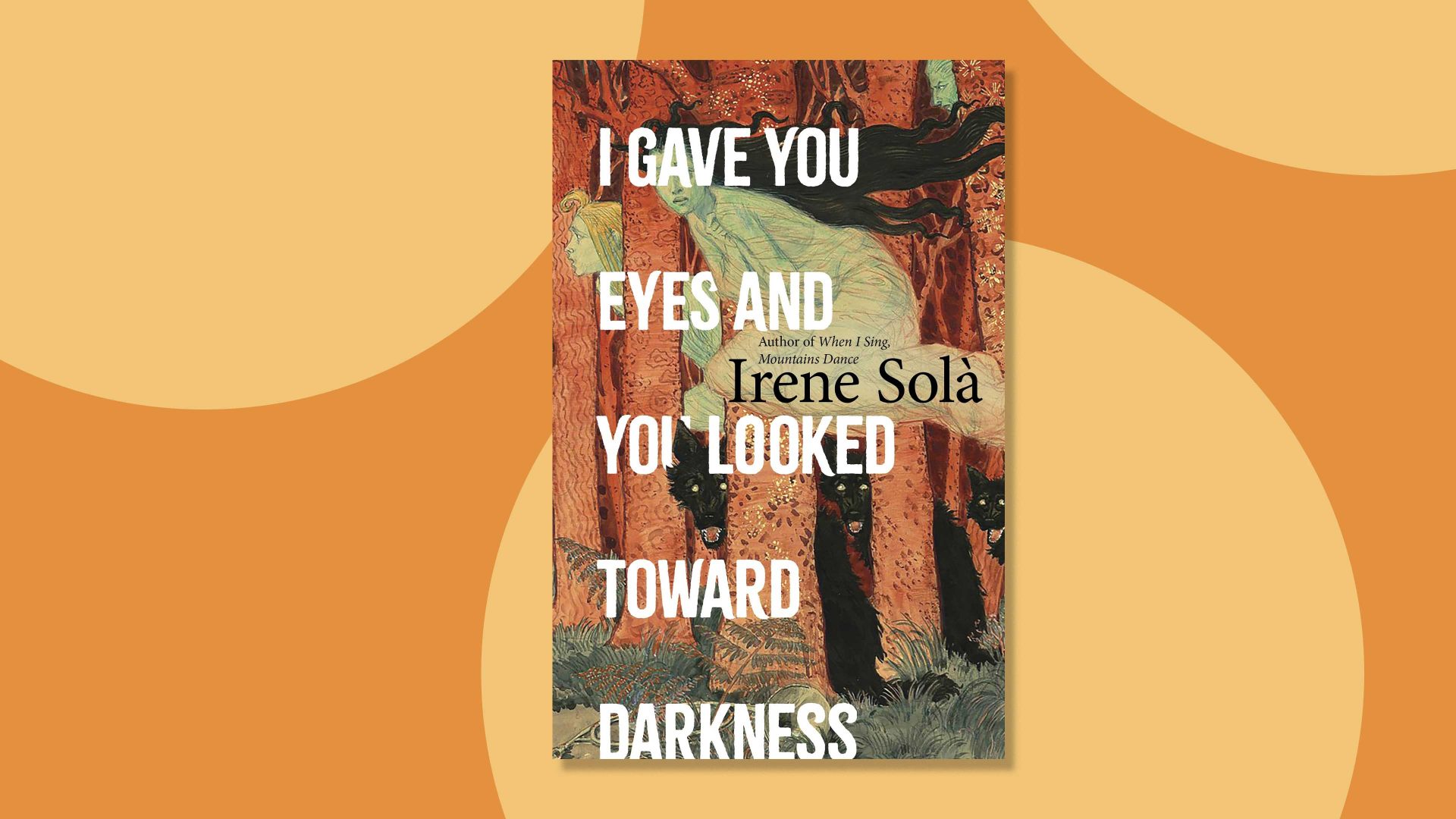

Irene Solà’s work is otherworldly in the extreme, but so beautifully conceived, so bewitching in its delivery that it is impossible to put down. It pulls you into the undergrowth among the wolves and the devils and makes you confront your humanity.

Author of the equally compelling When I Sing, Mountains Dance, Solà is adept at conjuring visions of a natural world that is as familiar as it is strange.

I Gave You Eyes and You Looked Toward Darkness is very much in this vein, creating a rich, beautiful landscape, shot through with horrors. It is a bewitching novel and if you are a fan of Elena Ferrante, or Natalia Ginzburg or even Ayanna Lloyd Banwo, you will certainly be susceptible to its charms.

Solà leans heavily on the magical realism of Spanish and Latin American tradition, whispering tales of devils and lost souls, an earth populated always with the endless meanderings of the dead and a bristling darkness through which its living characters must push and pull. It is fitting also that chapter 3 is introduced with a quotation from Pedro Páramo, Juan Rulfo’s masterpiece of Mexican Revolution, which is similarly one part exorcism and two parts necromancy.

Like Rulfo’s and those of Gabriel García Márquez and others, Solà’s novel is a layering of time, in which the living coexist with the dead and the “mirrors” of mobile phones and “horseless carriages” that represent more modern times drift in and out of a more medieval-feeling setting. Solà’s women’s lives are only brushed lightly with historical context; there is a sense of the Spanish civil war, of murders by bands of fascists, of the faraway rumbling of a world war in France, but these are muted.

These events come into the farmhouse that houses four generations only through the words and violence of men, a perpetual savagery that provides the backdrop and the justification for the women’s misdeeds. The women are both the manipulators and the manipulated, steering the plot through repeated pacts with the devil, seeking any agency they can in a world in which they are at best sitting ducks and at worst chief architects of their own misfortunes.

Suggested Reading

Universality, satire that’s highly in tents

These generations of women are evocative of Natalia Ginzburg’s spinsters and adolescents, heavy with the weight of experience and living a strong, embodied existence, more in touch with the rough births and hard labour of their female ancestors than any of their contemporaries. This is an inward-looking femininity, which spurns the male gaze but is no less punishing in the female glare that it turns on itself.

There is Bernadeta, the elderly woman facing death, but the house vibrates constantly with raucous laughter of her sister, her daughters and granddaughters, her elderly mother, Joana. The modern girl, Alexandra, haughty and confident as she jumps into her boyfriend’s Audi, is no more or less in control of her relationship than when her great grandmother followed the wolf-hunter up the mountain, days into their marriage.

These women cook together, hate together, punish each other compulsively and cackle at the filthy jokes and mythical stories of the landscape that surrounds them. They gossip, they slice and they clean. They sate their carnal appetites in every way they can.

At one point, they try to eliminate male influence altogether, only to be dragged back by one encounter from the past or from the future, leading to another birth, another woman. This is a novel of matriarchy, of the hardness and softness of women as they care for one another but also as they fight – all claws and teeth – to survive among the wildness of men and of beasts.

Solà’s novel is heavily saturated with the places, myths and relics of the Catalan landscape, ancient tales of children eaten alive, men with animal’s bodies and landscapes riven with conflict and intrigue. This magical world – as it does in its Latin American iterations– is used to draw out the contrasts between the patriarchal, colonising society of Castile Spain, and a more superstitious, traditional but powerfully independent way of life.

The use of stories, histories and recipes that are emphatically Catalan, read through the prism of a female experience rooted in landscape and the body, adds to this sense of a life at odds with the outside world.

The effect is at once panoramic and claustrophobic, bound tightly within this matriarchal home, the novel expands outward, taking in life, death, violence, colonialism and war before shrinking back again to an old woman, alone with her impending death. Breathtaking.

I Gave You Eyes and You Looked Toward Darkness by Irene Solà, translated by Mara Faye Lethem, is published by Granta.

Katherine Cooper is a writer and academic