In late September, Ahmed al-Sharaa addressed the UN General Assembly in New York. “I declare before you today the triumph of truth over falsehood,” Syria’s 42-year-old president told delegates. “Syria is reclaiming its rightful place among the nations of the world.”

Al-Sharaa was the first Syrian head of state to address the UN since Nureddin al-Atassi in 1967, who gave a speech shortly after the Six-Day War, when Damascus lost control of the Golan Heights, which Israel eventually annexed in 1981. Al-Sharaa is too young to remember that history. But he’s lived with its consequences.

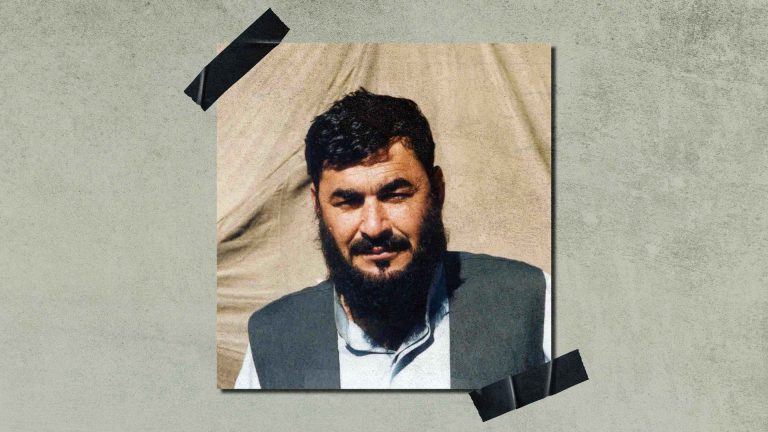

Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa was born in October 1982 in Saudi Arabia, returning to Damascus as a small child. In 1967, his grandfather was forcibly displaced from Fiq, then a small town in the Golan Heights in south-western Syria. The latter part of the nom de guerre al-Sharra later adapted as an Islamic fighter – Abu Mohammad al-Golani – was a direct reference to his ancestor’s homeland.

In September 2000, during the Second Intifada – as Palestinians in Jerusalem, Gaza and the West Bank protested the Israeli occupation – al-Sharaa, then 18 years old, looked on with quiet admiration. The following September, al-Qaeda’s attack on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon provided another source of ideological inspiration. “Anyone who lived in the Arab world who tells you he wasn’t happy about [9/11] would be lying,” al-Sharaa told American journalist Martin Smith in the documentary The Jihad (2021).

By the time a US-led coalition had invaded Iraq in March 2003, al-Sharaa had already travelled there to fight. Two years later, he joined the Iraqi insurgency, integrating into the ranks of a Salafi jihadi organisation that became Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) in 2006. US troops arrested al-Sharaa the previous year, in Mosul, northern Iraq. He spent five years in Abu Ghraib and Camp Bucca, where the CIA secretly tortured detainees in US custody.

In prison, al-Sharaa wrote a 50-page thesis about bringing jihad to Syria.

Upon his release, al-Sharaa held a meeting with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, then the newly appointed head of ISI. Elaborating on his prison thesis, al-Sharaa stressed two points.

The insurgency in Iraq was against a foreign occupying power. The fight in Syria, though, he insisted, was a revolution against Syria’s then president, Bashar al-Assad. Al-Baghdadi was so impressed he promised al-Sharaa a stipend of $60,000 a month, for six months.

In August 2011, al-Sharaa and six al-Qaeda operatives left Iraq, strapped with suicide belts in case they were caught. They made it safely across the border to Syria, then six months into a civil war.

The conflict began in March 2011, in Daraa, in southwestern Syria, where 15 boys were arrested by the government for spray painting graffiti calling for the removal of Assad.

Many Syrians shared that sentiment, which they expressed in street demonstrations that followed into that summer, attracting hundreds of thousands. The revolutionary fervour was influenced by the Arab Spring, a wave of pro-democracy demonstrations that began in 2010 in Tunisia and spread across the Middle East and North Africa.

But Assad—who trained as an ophthalmologist at the Western Eye Hospital in London in the early 1990s— wasn’t interested in compromise or reform. He’d taken the job as president reluctantly, after his father, Hafez, died of a heart attack in 2000. Since 1971, Hafez Assad had ruled Syria as a police state, teaching his son that violence, and locking people away for a long time, helped make the political opposition disappear.

At the beginning of 2011, Assad told The Wall Street Journal that the Syrian uprising was akin to a plague of microbes. That December, the UN high commissioner for human rights, Navi Pillay, announced that over 5,000 people had been killed in the Syrian civil war.

The following month, al-Sharaa set up Jabhat Al-Nusra, which defined itself as the front of support for the Syrian revolution. The radical Sunni Islamist group also emphasised their opposition to western countries, whom they accused of being complicit in crimes against Muslims. They criticised Turkey too, claiming the NATO member was not fully committed to Islam.

Adhering to strict Salafi principles, Nusra saw itself as part of a wider global jihadi network. “This trend championed by al-Qaeda since the 1980s, spread across the Muslim world, promoting the idea that regimes collaborating with the West and failing to implement Islamic law were illegitimate,” write Patrick Haenni and Jerome Drevon, two Swiss political scientists, in their new co-authored book, Transformed by the People.

Both authors specialise in jihadism, political Islam, and conflict mediation and resolution. They have carried out more than a decade of field research in northwest Syria, which eventually led them to interview al- Sharaa and his close associates, over a period of five years.

Within a year of its founding, Nusra evolved from an army of six men to 5000. Some of the cash that allowed the group to grow came from private donors in Gulf states, like Qatar and Kuwait. Nusra also kidnapped foreign civilians and took in tens of millions of dollars from ransom payments.

By the summer of 2015, Nusra controlled most of Idlib: a province in northwestern Syria that borders Turkey. There, the Islamist group established Sharia courts and took over the running of local government services.

Suggested Reading

When the Taliban shut off the internet

But Nusra also tortured their prisoners, and, using the Islamic penal code, carried out executions against individuals accused of partaking in extramarital relations, prostitution and apostasy. In Idlib, Nusra banned music, smoking and gender mixing too.

Rania Abouzeid was embedded with Nusra during its early years in the Idlib province and has described the group as effective, disciplined fighters, who won the respect of local communities, but who could be equally capable of ruthless violence. The Lebanese Australian journalist elaborated on this topic in No Turning Back: Life, Loss, and Hope in Wartime Syria (2018).

“I knew many of them for years,” Abouzeid told me in an interview for New Humanist, shortly after the book was published. “You see why they claim to carry out these acts [of violence], believe the things they do, and you see their thoughts, actions and worldview— you see how in some cases it changes.”

That evolving belief system is the central focus of Haenni and Drevon’s book, which begins on December 8, 2024, when Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow, after a rebel alliance— led by al-Sharaa and the Islamist group, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) — entered the Syrian capital, Damascus. After a half a century, the Assad regime collapsed like a house of cards.

Its last 14 years had been especially brutal. Syria’s major cities— including Aleppo, Homs and Raqqa — were subjected to relentless bombings. Thousands of Syrians were put in prison; the population was attacked with chemical weapons; hundreds of thousands were killed, and a further 13 million were displaced from their homes.

Haenni and Drevon provide a detailed account of the various twists and turns that al-Sharaa encountered before taking the road to Damascus. A crucial turning point came in April 2013, when al-Baghdadi announced a plan to integrate Nusra into the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Al-Sharaa wasn’t consulted about the move. Fearing he would lose half of his fighters to ISIS, he wrote to al-Qaeda’s co-founder, and then leader, the Egyptian physician, Ayman al-Zawahiri. “I conditioned my pledge of allegiance to al-Qaeda on the idea that we will not use Syria as a launching pad for external operations,” al-Sharaa tells both authors here.

But in July 2016, Nusra parted ways with al-Qaeda, too. The move was announced in a press conference by al-Sharaa, then one of the world’s most wanted terrorists, who had a bounty of $10m on his head from the US State Department.

Dressed in an army combat jacket, and wearing a white turban on his head, al-Sharaa publicly distanced himself from the al-Qaeda brand by paying tribute to its founding father, the late Osama bin Laden. Al-Sharaa also thanked al-Qaeda for their “blessed leadership”.

From this point on, though, al-Sharaa let go of a fundamental belief that had guided his political thinking since the turn of the millennium: global jihad. Instead, he focused on local details he felt were needed to win the Syrian revolution. Nusra was dissolved and became known as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, which eventually transformed into Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in January 2017.

Suggested Reading

Bashir Noorzai, the Taliban’s godfather

That October, HTS played a leading role in the establishment of the Salvation Government—a civilian governance project that ran a de facto state in the Idlib province. But HTS did not have the financial resources to govern 3.2 million people, so it outsourced many functions of government. Local tribes, for instance, were asked to administer the law in murder cases.

Allegedly, HTS also murdered people who did not share its worldview. This included Syrian journalists and activists, who promoted freedom of expression, such as Raed Fares and Hamoud Jeneid. “Both faced repeated threats due to their activism and were ultimately assassinated in November 2018 by unidentified gunmen, which many activists blamed on some HTS commanders,” write Haenni and Drevon.

Al-Sharaa, meanwhile, reassessed his previous views about Turkey, coming around to the idea that Ankara could prove useful to mediate with major global powers, like the US, Russia and Iran: all of whom had their own vested interests and military presence in the Syrian civil war. Al-Sharaa also understood that Turkey, with the world’s ninth-largest army, would be vital in helping HTS win a war against former comrades from al-Qaeda and IS.

“HTS launched a counter-insurgency campaign to dismantle IS networks in a series of raids and arrests. Some of these operations [resulted] in the public execution of IS militants,” Haenni and Drevon write. “HTS also [wanted to prevent] any potential resurgence of al-Qaeda-related networks in the region.”

In early 2020, Turkey deployed an estimated 10,000–12,000 troops to Idlib to deter a looming offensive there by the Assad regime. Since then, HTS has turned a fragile partnership with Turkey into a political alliance. HTS gradually used that relationship to edge closer to the West.

Last December, state representatives from across the world rushed to Damascus to meet and greet al-Sharaa, his intelligence chief, Anas Khattab, and the foreign minister Asaad Hassan al-Shaiba. The latter two individuals were then still designated as terrorists by the UN.

In July, the then UK foreign secretary, David Lammy, met with al-Sharaa in Damascus. “The UK stands ready to support the new Syrian Government,” Lammy tweeted, after becoming the first UK minister to visit Syria in 14 years.

That same month, Donald Trump signed an executive order that lifted economic sanctions on Syria. White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, said the move was designed to “promote and support the country’s path to stability and peace.”

But many obstacles remain. In late June, a suicide bomber detonated an explosive vest inside a Greek Orthodox church on the outskirts of Damascus, killing 25 people. The first attack of its kind in years in the capital, Syrian state media initially claimed it was carried out by IS.

That same month, Reuters’ Maggie Michael wrote an investigative piece about a massacre that occurred in March, in Baniyas, a coastal city in western Syria, where more than 1,500 Syrian Alawites were slaughtered in bloodthirsty revenge murders. “The investigation [identified] a chain of command leading from the attackers directly to men who serve alongside Syria’s new leaders in Damascus,” the article reported.

In late August, Israeli drone strikes near Damascus killed six Syrian soldiers, which Syria’s foreign ministry condemned as a violation of international law and a breach of its sovereignty. Since last December, Israel has carried out hundreds of similar airstrikes across Syria.

But security isn’t Syria’s only concern right now. For ordinary citizens, it’s putting food on the table and finding somewhere to live.

This past February, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) published The Impact of the Conflict in Syria. The report noted that nine out of ten Syrians presently live in poverty and face food insecurity; 50% of the country’s infrastructure has been destroyed or rendered dysfunctional; and 75% of the population now depends on some form of humanitarian aid, compared to only 5% in the first year of Syrian civil war.

Under these testing conditions, can al-Sharaa survive? His backstory suggests so. He has, after all, outlived most of his former bosses and paymasters.

In March 2019, shortly after a US military raid in northern Syria, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi killed himself and his two children by detonating a suicide vest. In late July 2022, Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by a CIA-operated remote-piloted aircraft that fired two Hellfire missiles at a safe house in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Luck, courage, charisma, violence, and careful strategic planning, have all played a part in al-Sharaa’s remarkable survival story. So too have political infighting, patience and pragmatism. Haenni and Drevon write about Syria’s present government as “a former al-Qaeda franchise allowing itself to be “transformed by the people” within “a silent revolution”.

Both authors claim al-Sharaa is neither a democrat, nor an autocrat, but an optimistic realist, learning, on an ad hoc basis, how to win the respect of the international community.

The intended outcome, for now at least, seems to be raising living standards for ordinary Syrians, and bringing the country back from the brink of disaster.

In this new-found political reality, al-Sharaa deems compromise a worthy price to be paid for long-term political survival. But will it be enough to save him, and Syria?

Transformed by the People by Patrick Haenni and Jerome Drevon is published by Hurst Books for £19.99