In August 2001, the little black golly was finally retired. For more than nine decades, the fuzzy-haired, black-faced doll – originally called a golliwog – featured on the labels of the British jam brand, Robertson’s. “We’re off to Robertson’s land. See you at tea-time,” proclaimed the jam-jar mascot in a TV commercial in the early 1970s.

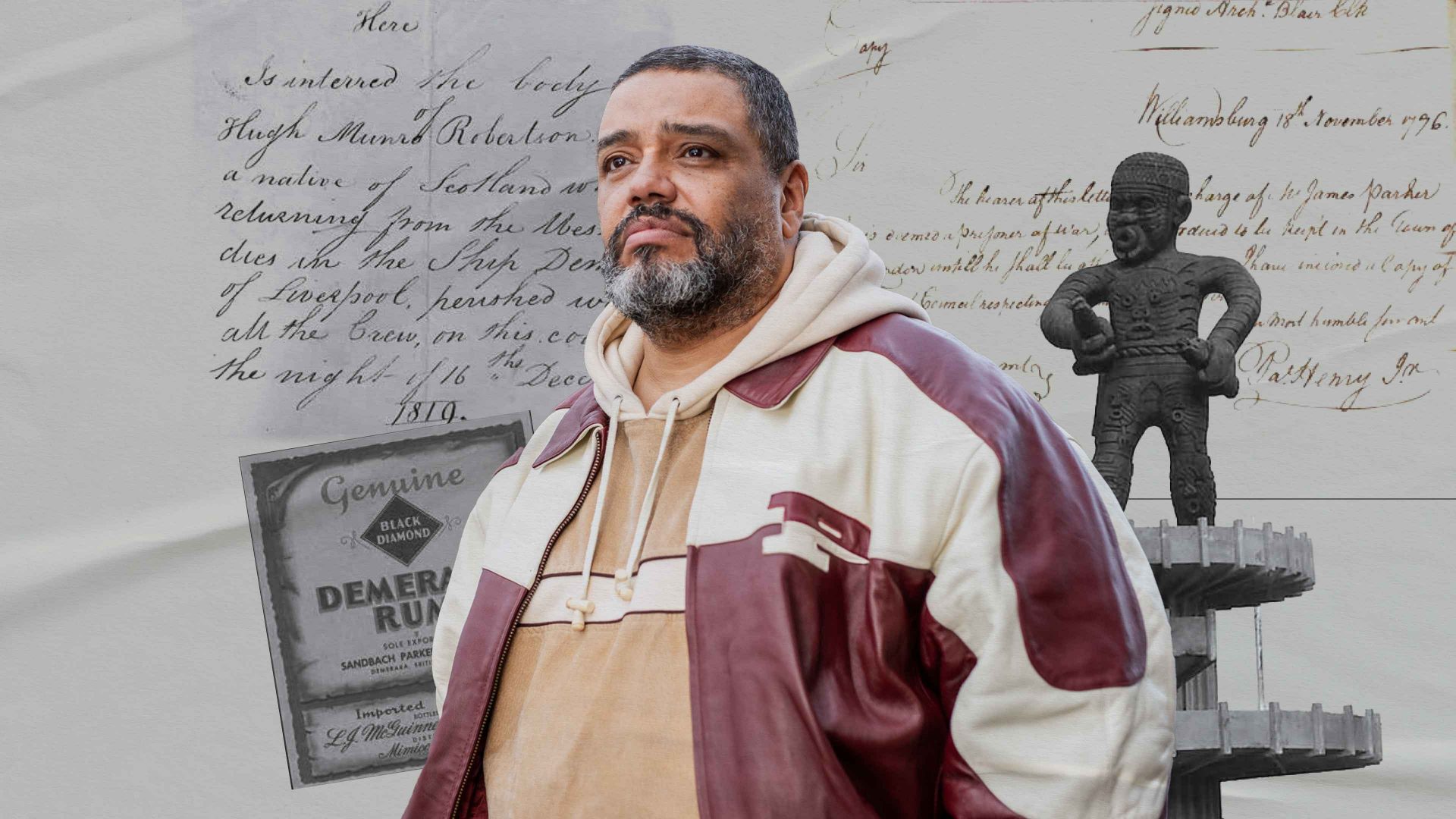

Back then, it was tough to be a mixed-race kid in Netherley: a council estate on the outskirts of Liverpool with a white majority population. The goofy Robertson’s ad didn’t make life any easier for Malik Al Nasir. The British author, academic, and performance poet recalls how other kids from the estate would gang up and sing “See you at tea-time” in unison.

Sometimes adults joined in on the casual racism. Walking home from primary school one afternoon, a fellow classmate’s father told Al Nasir he had a disease and that he should go back to where he came from: Robertson’s Land.

How does an eight-year-old process such cruelty? Al Nasir contemplates the lasting psychological scars of these childhood traumas in his book Searching for My Slave Roots. “Being told to go back to where you came from had a profound effect upon me,” the 59-year-old writes. “It made me ask myself: where did I come from?”

It’s taken Al Nasir two decades of research to come up with an adequate answer.

“My ancestors were enslaved by the multinational conglomerate-colonial-enterprise, Sandbach, Tinne & Co— who once prided themselves in dealing in [what they called] prime, gold coast negroes,” he explains from his home in Liverpool.

Between 1700 and 1807, the city’s port— which sits on both banks of the River Mersey and meanders out to the Irish Sea— was at the epicentre of Britain’s triangular, transatlantic slavery economy. Typically, merchants fitted out and supplied their ships in Liverpool.

The ships then carried goods to West Africa, where slaves were picked up and transported across the Atlantic Ocean to sugar plantations in the Caribbean.

It’s estimated that 1.5 million enslaved African slaves travelled on these ships, which began their journeys in Liverpool. Al Nasir learned that his ancestors were employed on both sides of this monstrous operation: as both slaves and slave traders. Ironically, Robertson, a name with Scottish roots, would feature prominently in the story.

Al Nasir’s relationship with his own name is complicated. He was born Mark Parry in Liverpool in 1966. The surname on his birth certificate comes from his mother, Sonia Parry, who hails from Dyserth, a small village in North Wales.

During his early 20s, he went by Mark Trevor Watson, momentarily adapting the surname of his father, Reginald Wilcox Watson. Then in 1992, aged 26, he converted to Islam, changing his name to Malik Al Nasir.

Reginald Watson was born in 1918, in British Guiana: a plantation colony famed for sugar and rum. The only English-speaking country in South America gained its independence from the UK in 1966, and four years later became the Republic of Guyana. As a young man, Reginald cut sugar cane on the flooded fields of what remained of the Blairmont Plantation, owned by Sandbach, Tinne, a British importer with offices in Liverpool.

Reginald left British Guiana, aged 18, in 1936, and travelled the globe as a merchant seaman before settling in Britain after WWII. In 1974, he had a stroke (he would never walk again, and died seven years later) and Al Nasir was taken into Liverpool’s local authority care system, where he suffered physical and racial abuse.

He reflected on this troubled youth in Letters to Gil (2021, a memoir mostly focused on the author’s close bond with Gil Scott-Heron, whom he first in the mid-1980s, when the American jazz poet, singer, and spoken-word performer was playing a sold-out gig at Liverpool’s Royal Court Theatre. Scott-Heron became a father figure and cultural-mentor-teacher, encouraging Al Nasir—then semi-illiterate— to self-educate.

In 2003, Al Nasir also took a renewed interest in his father’s homeland after watching Andrew Watson, Scotland’s Lost Captain: a BBC documentary that told the story of the world’s first black international footballer. Born in the province of Demerara, British Guiana, in May 1856, Andrew Watson was the son of Peter Miller Watson, a wealthy Scottish sugar planter, and Hannah Rose, a Guyanese woman.

Educated in Halifax, West Yorkshire, Andrew Watson captained the Scottish football team in 1881, leading them to a 6-1 win over England at the Oval. His flamboyant passing style is said to have revolutionised football in late 19th-century England.

“The football side of that BBC documentary was well researched, but many details about Watson and his family were incorrect,” Al Nasir explains. “The BBC speculated that Watson was the product of a shameful liaison and that he died in Australia. In fact, he died in southwest London and is buried in Richmond Cemetery.”

Keen to correct the historical record, Al Nasir contacted Scottish film producer, David Donald, who made a follow-up documentary, Mark Walters in the Footsteps of Andrew Watson (2021) for BBC Scotland. It was presented by Walters, a former England footballer who also shared details about the racist abuse he endured while playing for Glasgow Rangers in the late 1980s.

In the final scene, Al Nasir stands alongside Walters at Watson’s grave. For many decades it had fallen into disrepair. But a fan-based crowdfunding campaign raised enough to have it refurbished. It was a poignant moment for Al Nasir, who was paying respects to a distant cousin.

Andrew Watson’s father, Peter Miller Watson, was one of five brothers born to James Watson and his wife Christian, née Robertson, from Orkney, Scotland. Most of the Watsons boys ventured out to British Guiana in the 1820s, seeking their fortunes in the family business.

“I believe I’m derived from the lineage of one of those brothers, William Robertston Watson,” Al Nasir explains. His research suggests William Robertston Watson fathered a boy, Henry, with an unknown slave woman. Al Nasir believes Henry and this woman were the parents of his grandfather, George Edward Watson.

Suggested Reading

The myth of England’s monocultural past

Joining the missing details of this complex family tree together wasn’t easy, says Al Nasir. “When I found my father’s birth certificate, his father was not stated on it. But I later returned to Guyana and found the original birth record. This states that Reginald’s mother was Olivia July, and that George Edward Watson— who is stated as a friend— was present at the birth. He is my grandfather.”

In Guyana, Al Nasir interviewed many distant cousins from the extended Watson clan.

He also acquired other official documents. One suggested that his grandfather, a black schoolmaster, inherited dozens of acres of land, formerly owned by the Sandbach, Tinne plantation. Al Nasir claims this could only be possible if it was gifted from another member of the Watson family that had a financial stake in Sandbach, Tinne & Co: a business with a global reach that was in operation from 1814 to 1975.

The company’s roots, however, go back to the 1790s, with George Robertson, a Scottish slave trader. His apprentice, Samuel Sandbach (who later became a partner in the business and Lord Mayor of Liverpool) married George Robertson’s niece, Elizabeth Robertson, who was a sister of Christian Robertson. “That is where my family connection comes in,” Al Nasir explains.

This family history has an in-built bias though. It was written by slave traders. “If you go to the baptism records of slaves, you see a first name but perhaps no surname, or it doesn’t give, say, an actual date,” says Al Nasir. “This deliberate attempt to obscure records of black children made it difficult to put my [family tree] together. I had to reverse engineer it, through other variables, like who inherited the land.”

Private business letters also helped. Al Nasir discovered a pricey collection on eBay, which he bought by maxing out his credit card. Today, the letters are on public display, as part of Sandbach, Tinne Collection at the University of Cambridge, where Al Nasir recently completed a PhD in history.

The letters reveal that social mobility was possible for certain black and mixed-race children, like Andrew Watson. But such cases were rare exceptions.

White privileged men from families like the Sandbachs, Robertsons, and Watsons all had copious amounts of black children, many of whom “who were often born of rape and sexual exploitation,” says Al Nasir. “Most black people in the Americas and Caribbean have white DNA that comes from the sexual exploitation of black women,”.

The letters also found solid evidence that Sandbach, Tinne & Co were illegally trafficking enslaved Africans into Demerara as late as 1847, even though Britain had imposed a ban on the slave trade in 1807, and a ban on slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

During this period, many prominent British slaveholders started donating their money into public philanthropy. A guilty conscience? Perhaps. But the timing was no coincidence.

Slavery was then being legally outlawed. Fearing that history might not be kind to them, these former British slave owners began to rebrand their image.

John Gladstone understood more than most why this positive publicity campaign mattered. The Scottish merchant traded in cotton and sugar in the early 1800s in Demerara and Jamaica, where he owned thousands of slaves. His son, William, was the most influential politician of the Victorian age: serving as an MP in the House of Commons for six decades and as British prime minister on four separate occasions, between 1868 and 1894.

A sitting MP and chair of the West India Association, John Gladstone played a crucial role in negotiating a compromise package of £20 million to slave owners for the loss of their ‘property’. The Bank of England administered the payment of slavery compensation on behalf of the British government.

With deep pockets, men like John Gladstone and Samuel Sandbach helped fund many public works and buildings in Victorian Britain, including churches, poor houses, libraries, museums, and universities. But these progressive cultural institutions and impressive decorative civic buildings were built by money derived from the blood, sweat and tears of slavery.

“The moment these Africans embarked on a slave ship leaving the gold coast, their names, identity, religion and language was all taken away,” Al Nasir explains. “They were forbidden to read or to write. They could be flogged or imprisoned or dismembered, which meant their Africanness was, in most cases, almost entirely removed from them.”

In a collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son (1955), James Baldwin wrote that studying his people’s history “forced me to recognize that I was a kind of bastard of the West. When I followed the line of my past, I did not find myself in Europe, but in Africa.”

Al Nasir addressed similar questions in a poem he wrote called Africa, which features in Letters to Gil. “There, I was on a quest to find my roots. But I didn’t go as far as I do in this book,” Al Nasir concludes. “That poem describes the first time I cast eyes on Africa. I was on an oil tanker, off the coast of Angola, and I could see the coastline through mist. I’d like to recite it now if I may…

“Africa, with your misty morning,

Here my heart, it’s begging I’m calling,

Africa won’t you shine a light for me.

Though I’ve travelled as an Englishman,

I’ve been yearning for my fatherland,

Alas, I’m so close I can see,

My Africa, in front of me.

Oh Africa, with your misty morning,

Hear my heart, it’s begging, I’m calling,

Africa, won’t you shine a light for me.”

Searching for My Slave Roots by Malik Al Nasir is published by William Collins