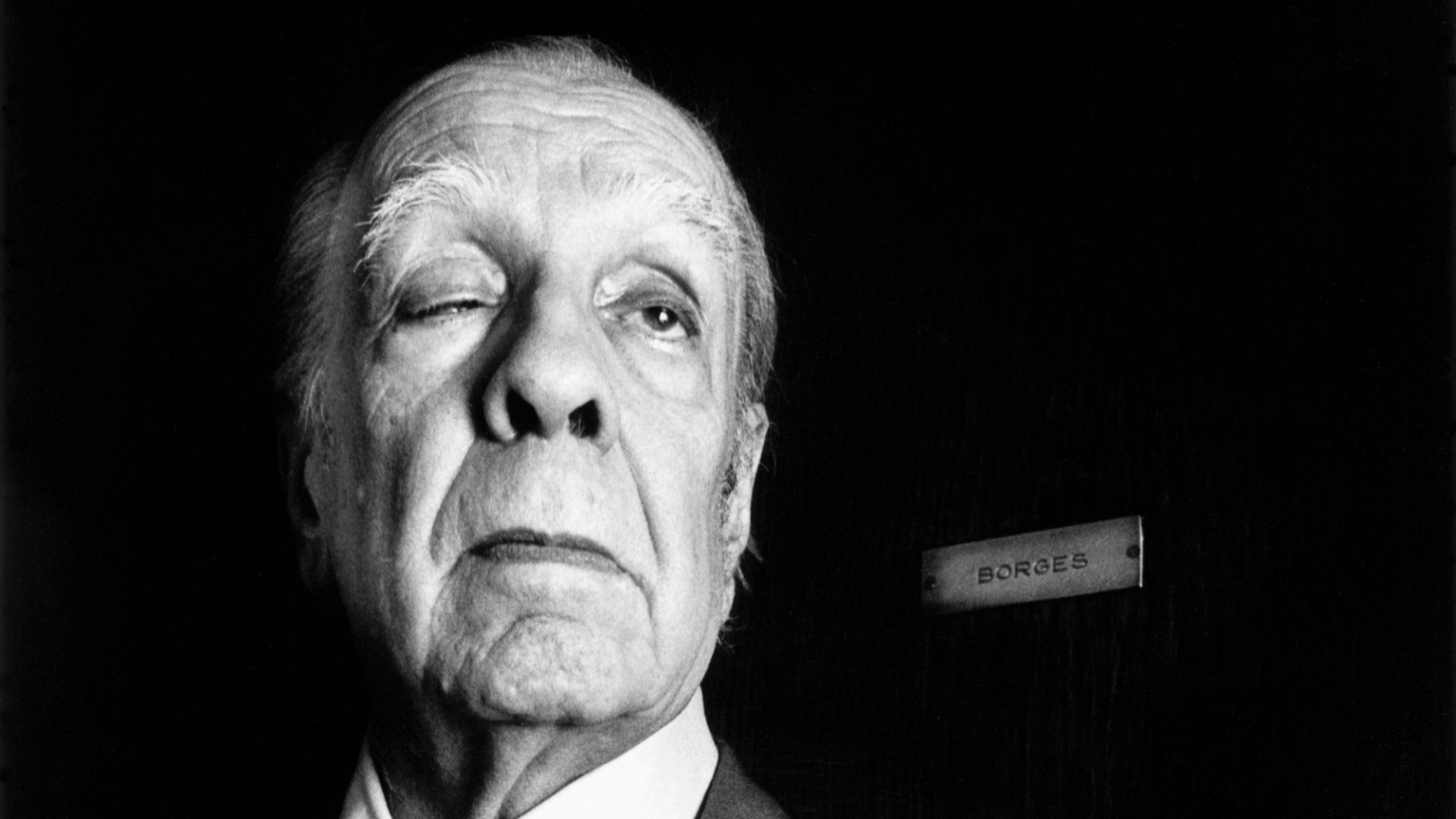

AUGUST 24, 1899 – JUNE 14, 1986

It’s 1931, and at a party in San Isidro in a house belonging to Argentinian intellectual Victoria Ocampo, two men shake hands. “He was 17 and I was just past 30,” Jorge Luis Borges would later remember of his introduction to Adolfo Bioy Casares. “It is always taken for granted in these cases that the older man is the master and the younger his disciple. This may have been true at the outset, but several years later, when we began to work together, he was really and secretly the master.”

A prolific, platonic relationship developed almost immediately. Borges and Casares fell into such intense conversation that their hostess reprimanded them for excluding their fellow party guests. Though they reluctantly agreed to circulate, within next to no time the duo were spending vast amounts of time together.

Though both a decade older and a far greater success than Casares, Borges would increasingly come to depend on Adolfo. Asked how the pair collaborated, renaissance man Alberto Manguel observed that “Working together in one of the back rooms of Bioy’s apartment, they reminded me of alchemists assembling a homunculus, creating something that was a combination of the features of both men and yet was unlike either of them.”

Admirers of Borges’ work will recognise the irony of a man fascinated by doppelgangers, coincidence and the blending of personalities cultivating the relationship he had with his protege. And as the older man began to lose his battle with glaucoma, the connection between the Dr Johnson-adoring Borges and Casares – his Boswell by any other name – grew stronger still.

Called upon to adapt a Borges short story for the BBC in 1992, the British writer/director Alex Cox was beyond surprised when he chanced upon a photo of Borges and Casares taken in the late 1960s. “It was remarkable,” writes Cox in his memoirs. “Here was Borges, tall, old, skinny, and blind, rising from his desk to shake the hand of Casares, also tall, old, skinny, and wearing the same suit and the same pair of spectacles. The similarity was striking even if you didn’t know who they were. Given that they were author and translator, it was as if Borges had turned his favourite literary device, the doppelganger, into a real person.”

If their working relationship was so close as to exclude all others, the same can’t be said of the men’s private lives, with Borges keen to prevent his compromised sight from interrupting his womanising, while Casares took up with Ocampo’s daughter Silvina. More pertinently, whatever they brought to one another’s work, Casares was among the many elements that helped Borges become a giant of Latin American literature. These included an insatiable appetite for reading, fuelled by the realisation that, like his father before him, Borges’ eyes would go long before he did.

Though he was born in Buenos Aires, Borges had a distinctly European upbringing. The son of a lawyer and a translator, young Jorge was fluent in English and Spanish by the time he turned 10, the same year he translated Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince into Spanish.

His interest in the Old World was further fuelled by his father’s decision to move the family to Switzerland in 1914. Adding French and German to his formidable list of languages, he continued to read voraciously. As for spending his formative years on the other side of the world, the effect of this only became apparent when, in 1921 at the age of 20, Borges returned home to Argentina.

With his early years as a writer taken up in part by translating Kafka and Lovecraft, the immediacy of his own work was affected by the complexity of the stories he wanted to tell – few authors have so frequently grappled with issues relating to infinity – and his preference for writing in languages other than his own.

As Borges explained to William F Buckley in 1977, “I find English a far finer language than Spanish… English is both a Germanic and a Latin language. With those two registers, for any idea you have, you have two words, neither of which will mean exactly the same…. It makes a whole world of difference if, in a poem, I speak about the Holy Spirit rather than the Holy Ghost since ‘ghost’ is a dark Saxon term while ‘spirit’ is a light Latin word.”

This disdain for his native tongue might explain why Borges was admired rather than loved in Latin America. Elsewhere in the world, he was raved over by academics and authors yet his work was too cerebral to achieve mainstream success. Neither this, not his failing eyesight embittered him. “I was always very near-sighted,” he said in 1971. “I long ago forgot what my grandparents looked like. However, being near-sighted I’ve vivid memories of the illustrations from the books I loved, from The Jungle Book to Huckleberry Finn.”

He was significantly more pissed off that he was never awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. “Not awarding me the Nobel Prize has become a Swedish tradition,” he once remarked, only half in humour. “They didn’t award it to me the year I was born and they’ve continued not awarding it to me every year since.”

In the end cancer spared the Noble committee’s blushes. Borges’ passing at the age of 86 couldn’t really be described as tragic but nor could it be said to have interfered with his influence upon generations of poets, authors, essayists, even mathematicians and scientists.

In the 40-odd years since Borges died, 30 of his short stories have been adapted for the screen. More pertinently, “Borgesian” has become an adjective, thrown about – perhaps a tad too casually – whenever a work embraces magic realism, fantasy and/or coincidence.

As for the enduring cult of Jorge Luis Borges, it doesn’t hurt that one work of art to which the term “Borgesian” certainly applies itself boasts a considerable cult. Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970) not only features characters reading and quoting from Borges’ stories but also centres on two very different men practically becoming one another.

So successfully do James Fox’s gangster and Mick Jagger’s rock star swap wardrobes and personalities that come the film’s finale, they are all but one and the same. At which point one can not help but think back to Borges and his own relationship with Casares, themselves very different gentlemen who after that fateful meeting in Argentina slowly became one another’s reflections.