Last weekend, I visited my local gastropub The Fox and Grapes on Wimbledon Common for a celebratory Sunday lunch. It was packed and the food and beer were excellent if pricey.

The Fox and Grapes is warm, bright, welcoming. It is perfectly positioned in one of the wealthiest parts of the country. The décor is charming. It is kid- and dog-friendly, just the place for a pie and pint after a vigorous walk searching for wombles.

The pub is named after Aesop’s fable about the hungry fox who, unable to reach some grapes it wanted to eat, walked off muttering “they were probably sour anyway”; hence the expression sour grapes. Which brings us to Kemi Badenoch.

On Thursday, January 8, aware that chancellor Rachel Reeves was about to exempt pubs from rising business rates – something the industry had convinced business secretary Peter Kyle must happen to stop an apocalyptic wave of closures – Badenoch launched an opportunistic campaign to not just keep pubs exempt from a business rate rise back to pre-Covid levels, but to slash pubs’ energy bills by £1,000 a year too.

In fact, the Tory leader went even further than that – her plan calls for the abolition of all business rates under £110,000 a year, at heaven alone knows what cost. It is yet another Conservative policy that will be “funded” by cutting benefits and “efficiency savings” in the civil service, so not really funded at all.

Yet Badenoch knows how to spot a rolling bandwagon when one passes. This one has been gathering momentum for a while, kick-started by the industry itself (before Christmas, several landlords and small pub groups banned Labour MPs from their locals) and recently given momentum by the Telegraph before she belatedly jumped aboard.

“Pubs are being treated by Labour like cash cows to milk instead of as places to protect,” Badenoch said, omitting to mention the 15,000-plus UK pubs that closed between 2010-2024, when her party was in power. She did not talk about Labour plans to allow longer opening hours and more pavement spaces either, although she may not be so reticent when it comes to plans to reduce drink-driving limits in line with those in Scotland, supposedly imperilling country pubs

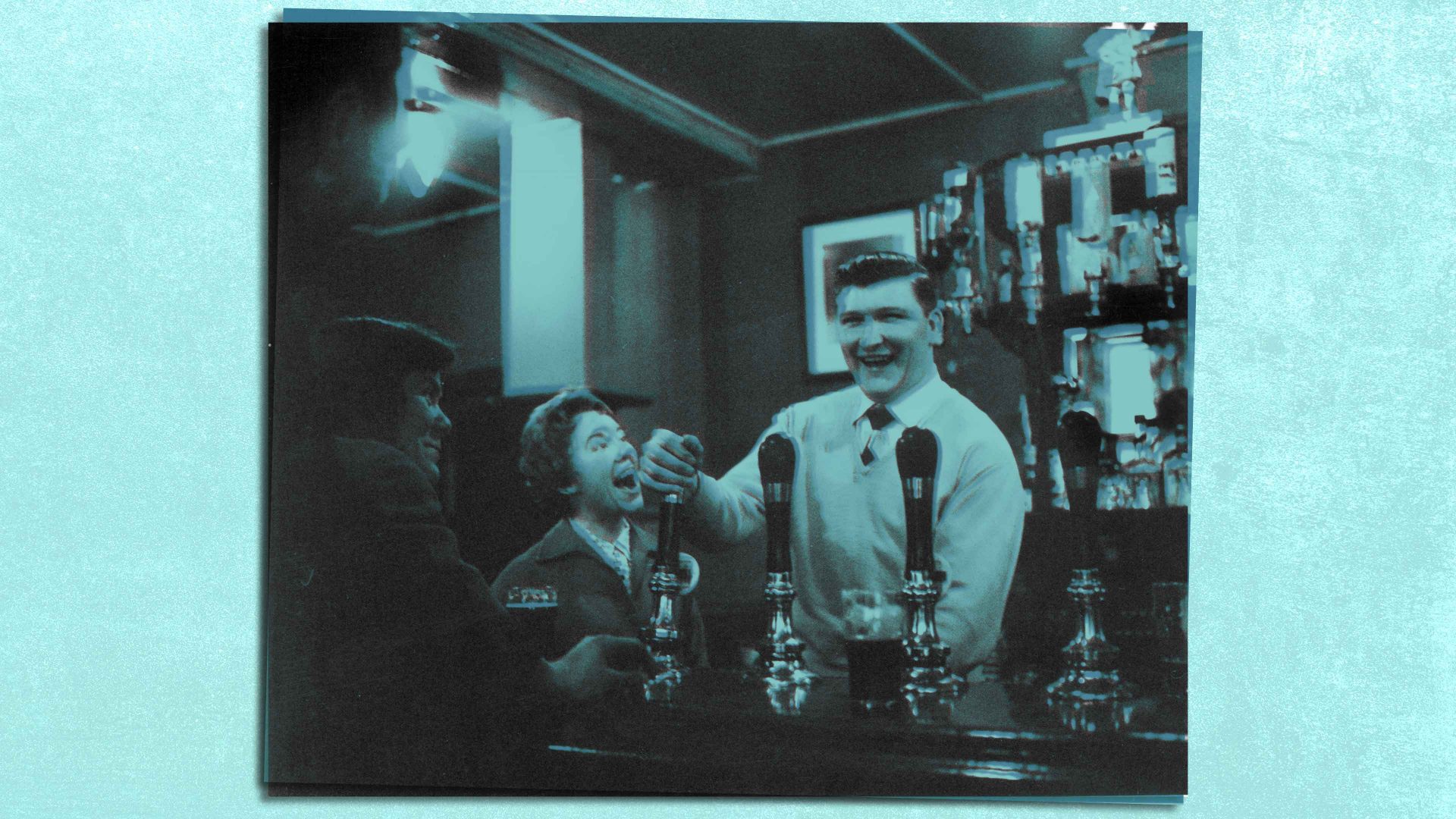

Though campaigners are insisting more must be done, the British pub industry seems to have played a blinder since Reeves announced the rates changes in November. They have talked about the pub’s special place in our hearts and our communities, conjuring up images of cozy snugs, warm pints and beaming mine hosts to full effect. For older generations of Britons for whom the pub has always been and still is part of the social fabric, this was pushing at an open door.

On February 9, it will be 80 years since George Orwell first tugged at the nation’s heartstrings with his essay The Moon Under Water, describing the perfect imaginary pub. This was a pub which had good food, a fire, no music, friendly barmaids who remembered your name, darts in the public bar and creamy stout. An ideal that is only ruined somewhat by Wetherspoon subsequently naming 13 of its drinking sheds The Moon Under Water.

But while we probably all know a favourite snug, cozy and friendly bar, the fact is that the traditional boozer has been under threat for years. The now-cancelled changes might have been the straw that broke the camel’s back, but the camel has been sick for a long time.

Sam Hagger, who owns and runs the Beautiful Pubs company in and around Leicester, has bucked this depressing trend. After starting out in 2008 at the tender age of just 24, he now has 4 pubs in his empire. He says he has succeeded when others have failed because he has learnt “to do the common things uncommonly well. You need to offer people something they cannot get at home, like ambience, conversation, hospitality, people to talk to, great food.”

Hagger highlights the fact that the local is often the centre of local life and for the elderly and lonely, is a lifeline, especially over Christmas and through the winter months. This should not be overlooked: one of my locals, The Alexandra, even offers free Xmas dinners for everyone on their own over the Xmas break.

But like everyone else, he is feeling the pressure. “Last year, despite very, very good turnover of a couple of million, we only made £9,000 profit after depreciation,” he says. “Then the government announced they were going to reduce the support for business rates, and hike the minimum wage; that was £200,000 of additional cost for our business.

“This year the rateable value of all four of our properties is increasing. And the minimum wage has been pushed up once again, so we will have to find another £60-70,000 this year.”

Raising the minimum wage was in Labour’s manifesto and remains a popular policy with the public. But not for publicans, who file it with higher rateable values, higher NI contributions, higher energy costs and higher alcohol duty on alcohol threats to the industry’s future.

Kate Nicholls, chair of the industry’s umbrella organisation Hospitality UK, told me that “The cost increases over the last couple of years have been something like 13-14% a year and price increases have only been 6%. We cannot pass on costs anymore because we are past that tipping point where customers will continue to pay those price increases.”

A certain amount of crying wolf follows all tax changes- just look at public schools – but for pubs the data is stark. We have lost a quarter of all them since 2000, and are now down to some 40,000 pubs in England and Wales, even if the largest recent losses came in 2013 and 2017.

Suggested Reading

Why Britain’s public services are so bad

It is true that like the minimum wage, other government decisions that had broad approval have negatively impacted pubs over the decades. First were the drink driving laws that were introduced in 1967, with limits tightened in 1974 and 1981. Then came the 2007 smoking ban, and in 2020 and 2021 pubs were shuttered for months on end in the Covid lockdowns.

Since then, Nicholls says, “a lot of post-Covid decisions by successive governments have imposed more costs on the sector. The industry is holed below the water line, margins across the sector have halved.”

That has all been made far more difficult by huge social and economic changes. Over a third of British adults do not drink alcohol, among them some migrants and health-conscious young people. Ongoing cost of living pressures have seen an era of pre-loading among the young – drinking cheaper booze at home before heading out and making a small glass of wine last the rest of the night at the pub, or downing a couple of cheap shots while dancing at a club.

An older generation has found that drinking at home is far, far cheaper than buying a round in a pub. Supermarket booze deals, ready meals, takeaways and wide-screen TVs with multiple channels and streamers are more than enough to keep many people at home.

And even if you want to go out for a beer, pubs are not the only place you can get a drink these days – restaurants, cafes, coffee bars, cinemas, and even garden centres have licences. The Fox and Grapes has to compete with the coffee cart on Wimbledon Common which allows dog walkers to stiffen their cappuccinos with a shot of Bailey’s.

No wonder some – like the political journalist John Rentoul – argue that pubs are an uneconomic sector. And no wonder that even with the new concessions, many will have to adapt to survive, and those which don’t will die.

Sam Hagger told me: “Some pubs can change, but some cannot. Country pubs which are not a destination, do not do great food, they are probably not sustainable. We do coffee and cake in the mornings, Sunday lunch, pub quizzes. It is not just about alcohol anymore”.

For those still fighting, there is hope. Kate Nicholls told me: “The pub is a great survivor; a pub mentioned in The Canterbury Tales (The George in Southwark) is still there. They are the great re-inventors, and they are at the heart of our community.”

So the George and the Fox and Grapes are probably safe for now – good pubs in wealthy areas normally thrive. Wetherspoon, able to drive down cost by bulk-buying its stock, is not going away either. Others will cling on because of relentless innovation, hard work and a willingness to deal with low margins.

But for many others, no matter who is in No 10, last orders is closer than you think.

Jonty Bloom is a former BBC business correspondent. His Substack is Jonty’s Jottings