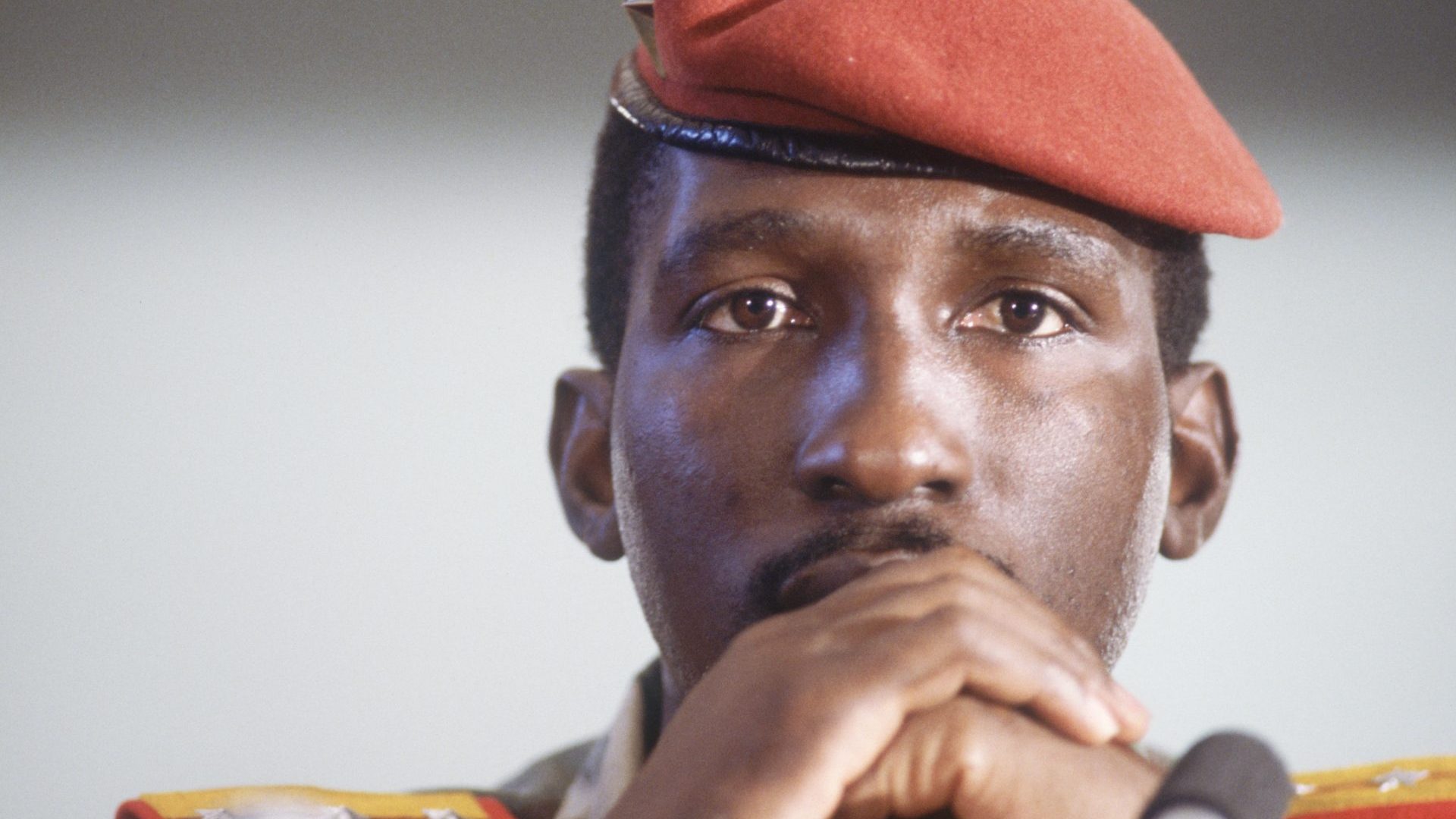

Thomas Sankara was expecting a long night. On the afternoon of October 15, 1987, fresh from a siesta, the man some called the Che Guevara of west Africa arrived at the Conseil de l’Entente, a government building in the capital of Burkina Faso. Ahead for the president lay meetings that were expected to run late into the evening.

Sankara was the last to arrive for a 4pm conference with 12 of his associates and allies. Sankara’s legal adviser Alouna Traoré was briefing them all on a recent trip to Benin when he was interrupted in full flow by the sound of gunfire and voices shouting “Get out, get out.”

Sankara, knowing that he was the person being looked for, stood up, told his colleagues to stay calm and walked out of the room, unarmed, with his hands up. At the doorway, he was shot dead at point-blank range.

Soldiers entered the meeting room, firing at each member of the cabinet. Traoré was hit and fell to the floor among his colleagues. He lay still, wounded but alive. Only when the assassins had gone would he understand that he was the only one of the dozen not to have been killed.

Across the city, more soldiers arrived at the office where Mariam Sankara worked. Not long ago, she and her husband had lain side by side for their afternoon sleep. The bed was still warm. Now she and her two sons were taken back to their home, under armed guard.

Mariam wouldn’t find out about the death of her husband for hours. She was 33 years old, he had been 37.

Later, she learned the truth: a coup led by Blaise Campaoré, a close friend of the Sankaras, had seized control of the country. The body of Thomas Sankara, along with the others, was hurriedly buried in a mass grave. The official line was an internal power struggle, that Sankara was a radical who had gone too far, that this new regime was vital for national stability.

Sankara had been the first president of what was once Upper Volta, a West African country that had gained full independence from France in 1960. Under his leadership, the country was given a new name, Burkina Faso: “Land of the Upright Men.”

Aged 33 and one of the youngest heads of state in the world, Sankara’s dream for this brave new world was for a society of equally upright women. “Comrades, there is no true social revolution without the liberation of women. May my eyes never see and my feet never take me to a society where half the people are held in silence. I hear the roar of women’s silence. I sense the rumble of their storm and feel the fury of their revolt.”

Suggested Reading

Emilie Schindler, one half of a team of equals

Sankara’s revolution was much more than one of military power and personal gain. His was one of nature: of trees, clean water and equality.

His Burkina Faso vaccinated millions of children. “He began to take steps to secure the country’s health through food self-sufficiency,” wrote historian and activist Perry Blankson. The goal was “the ability to satisfy food needs from its own domestic product.”

Being able to drink and wash with clean water was vital for his people: “We must choose between Champagne for a few, or safe drinking water for all,” Sankara said. He wanted to make it a tradition that everyone should plant a tree on their birthday.

It was this dedication to nature and equality that led to Sankara’s bloody removal. Strident voices believed that what the country needed most was military funds, not rural development projects. Action, it was felt, had to be taken.

After the death of his former ally, Campaoré led the country with relative political stability for the next 27 years. There were many though, who suspected they knew what had really happened on that Thursday in October.

In 2021, with Alouna Traoré as a key witness, Campaoré was found guilty of being involved in the assassination of the man who had been his friend. Sankara had often called him “mon frère jumeaux” – my twin brother. They used to play guitar together. They used to stay up late talking of Marxist theory and revolution.

“I ask the Burinabe people for forgiveness for all the acts I may have committed during my tenure and especially the family of my brother and friend Thomas Sankara,’” Campaoré wrote after being found guilty of complicity in murder. He never went to prison and now lives in exile in Ivory Coast, with Ivorian citizenship.

“Captain Thomas Sankara was a handsome, unpretentious young man who wanted to give his country dignity and hope,” the Economist wrote when reporting his death. “His country proved ungrateful.”

The gratitude is clear to see today, however, and the legacy of Sankara lives on. In May 2025, Burkina Faso inaugurated the Thomas Sankara Memorial Park, with a bronze statue of the man who not only gave the country its name but wrote its national anthem.

The capital city’s Boulevard Charles de Gaulle is now renamed as Boulevard Thomas Sankara and October 15, a day that should have been of meetings that went on for too long but ended in gunfire, has been officially declared a National Day in honour of Thomas Sankara. He would have insisted that the honour be shared with the allies who died alongside him.