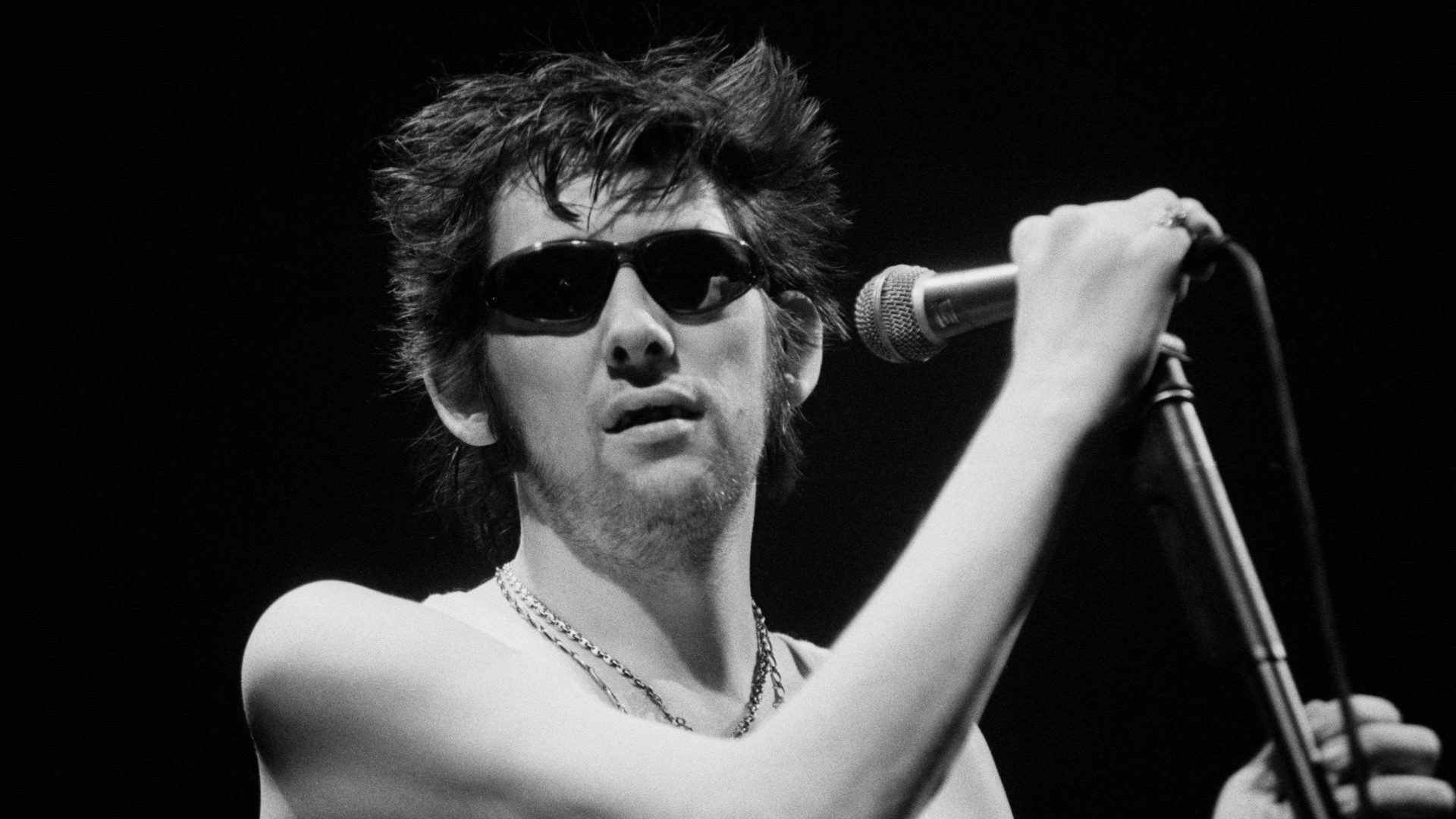

It’s St Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1988, and Shane MacGowan walks out on to the darkened stage at London’s Town and Country Club in dark sunglasses, looking every bit the punk messiah. He’s been drinking, of course, but tonight his slurred vocals have vitality and bite. The Pogues’ latest album, If I Should Fall from Grace with God, has been in the shops for eight weeks, and this is a night for celebrating its success – a night that will go down as one of the most raucous and legendary of the band’s career.

The Kentish Town venue is a home fixture for part of London’s Irish diaspora, and the crowd is buzzing, some of them close enough to the stage to be handed drinks by the band. There are special guests: Joe Strummer plays London Calling backed by James Fearnley’s frantic accordion, and the Specials’ Lynval Golding joins in for an Irish-tinged A Message To You, Rudy. And of course, there is Kirsty MacColl.

NME has called the new album “a thing of beauty, the bleakest of masterpieces.” Its penultimate song, The Broad Majestic Shannon, is one of the first tracks played tonight. An ode to the longest river in Ireland fits perfectly for St Patrick’s Day.

“It captures a sense of yearning for a home you will never see again,” founder member and tin-whistle player Spider Stacy will say later. “It’s a beautiful song about memory and love.”

The songs of memory and love pour out of them tonight. It’s proof of MacGowan’s rare ability to write about mood and place, to capture the rawness of what it is to be alive, to become the poet laureate of chaos and loss.

One of the first people to see this talent was his schoolteacher Tom Simpson, who kept many of the young Shane’s handwritten stories and essays, certain that this boy would become famous. Now, with a band influenced equally by punk and Irish folk, MacGowan’s tenderness and vision have made him just that.

It’s a measure of how strong the MacGowan songbook is, just three albums in, that the song for which he will be forever remembered comes less than halfway into the set. Fairytale of New York was everywhere the previous Christmas, when MacGowan was back with family in Tipperary.

Suggested Reading

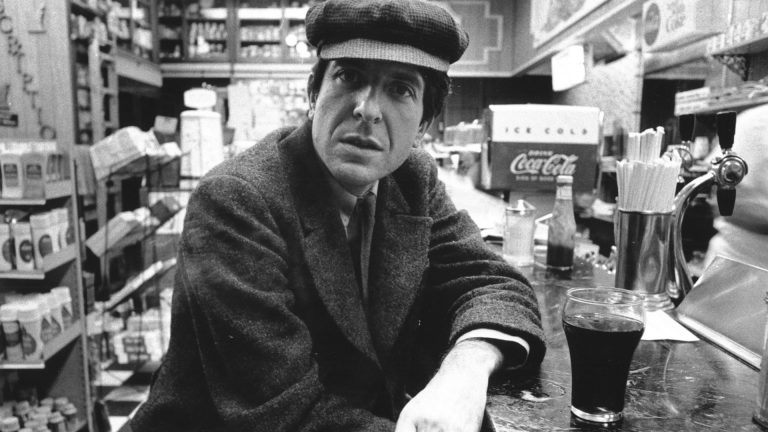

Leonard Cohen, the poet laureate of gloom

His sister Siobhan made a “Happy Fairytale” cake to mark his birthday on December 25, and to celebrate the song reaching No 1 in Ireland. In the UK, cruelly, it was kept off the top by the Pet Shop Boys’ cover of Always on My Mind, but tonight, as fake snow falls on the stage of the Town and Country Club, there is little doubt as to the identity of the long-term winner.

The song is followed by more MacGowan classics – Sally MacLennane, The Sick Bed of Cúchulainn, A Pair of Brown Eyes. The crowd are enraptured, not realising that there is an element of a last stand here.

Over the next weeks and months, the singer’s behaviour, exacerbated by drink and drugs, will grow increasingly frightening. MacGowan’s doctor in Dublin is soon warning that if Shane carries on with his lifestyle, he will have only six more months to live.

Instead, he will stumble on with the Pogues for another three years, his contribution increasingly erratic, his power diminishing. He’ll go on to release albums and play shows with a new band, the Popes, and work with people he loves, occasionally teaming up with MacColl at Christmas, performing with the Dubliners and duetting with Nick Cave on Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World, his voice once again evoking Tipperary and the Shannon as he sings about the trees of green and dark sacred nights.

He’ll reunite with the Pogues for joyous shows, although the toll of his lifestyle is visible. Ultimately, he will exceed the expectations of the doctor – and many other people – by some distance. Diagnosed with encephalitis, he spends much of his final months in hospital in Dublin, and dies from pneumonia in November 2023, with his wife and sister by his side and Fairytale of New York just beginning to take its annual turn on the radios of the UK and Ireland.

That MacGowan lives as long as he does is no small part due to Victoria Mary Clarke, who he’d met in a pub in north London in 1986. Soon after meeting him, Clarke realised she was “all in” with everything this troubled genius had to offer, and for 40 years they drank, meditated, laughed and battled. What he faced, she would face alongside him.

He loved that she was from the Gaeltacht, where Irish is the primary language. Although from an Irish family, MacGowan was born and grew up in England, and thought of the Gaeltacht as something definitively Irish, the Ireland he thought of when he closed his eyes. “He would talk to me about Ireland and Irish poetry, Irish music, Irish language. He was really impressed that I spoke Irish – all those things that I didn’t really think were in any way cool, he thought were very cool,” Clarke said.

Two years after her brother’s death, Siobhan MacGowan still walks by the river every day in Tipperary, The Broad Majestic Shannon forever in her thoughts. “I sing the song to myself… it’s beautiful,” she says. It was MacGowan’s wish that his ashes were scattered in the river. “He absorbed the magical mayhem of this place,” Siobhan says. “It would be the greatest influence on his life.”