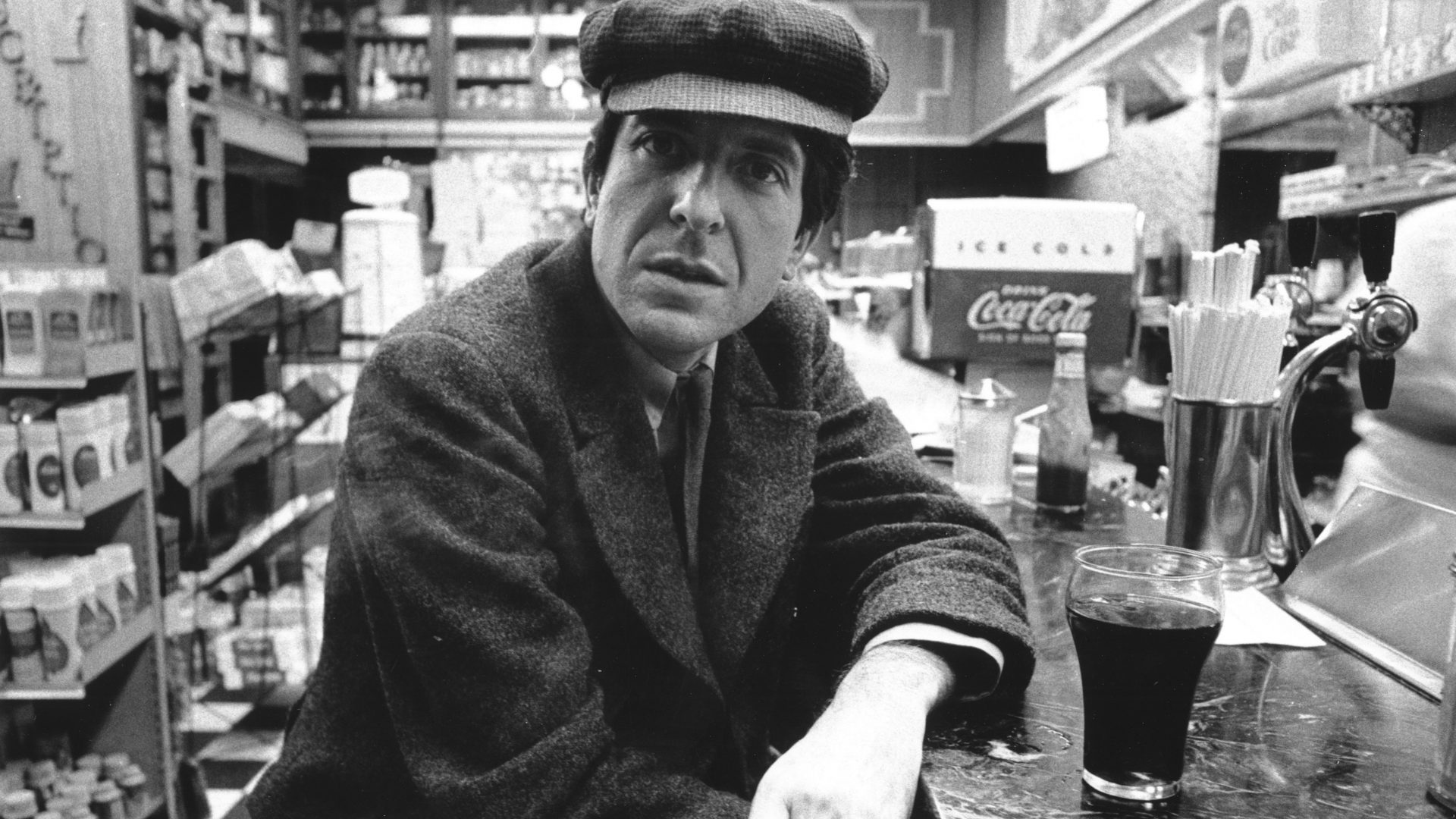

After a weekend of hostility and tension, Leonard Cohen walked on to the stage at the Isle of Wight Festival at two o’clock in the morning. “Greetings. Greetings,” he said, dressed in a smart linen suit. “Could I ask each person to light a match so I can see where you all are? I would love to see those matchsticks flare.”

It was the end of a long weekend, August 31, 1970. The festival had been on the precipice of disaster before the first person had walked through the fields, with death threats issued by groups opposed to a festival taking place on the site.

People without tickets had broken down fences, and protesters interrupted several acts’ performances, claiming the festival should be free. The island’s infrastructure had been torn apart with road congestion and cancelled ferries. By Sunday, the festival had been overwhelmed, security at breaking point, shops and stalls demolished, the scene one of “indescribable squalor and filth”.

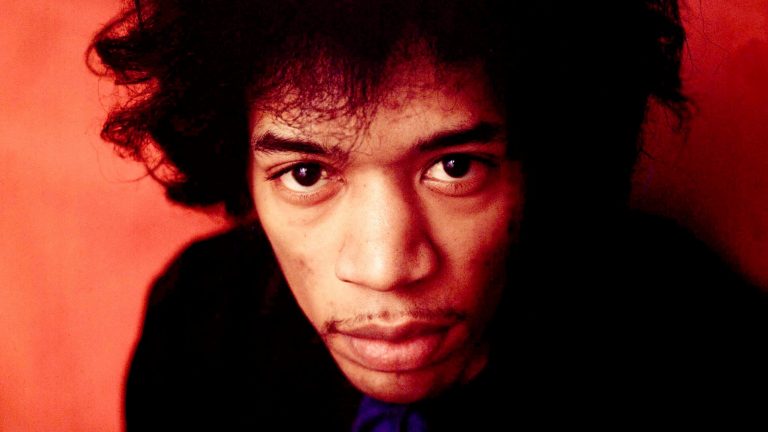

Cohen, the festival’s closing act, was confronted with a late-night crowd disappointed by the preceding Jimi Hendrix, who had battled technical difficulties and lighting problems. The Isle of Wight had not been treated to the Hendrix of Woodstock – instead, they saw an introspective, lacklustre set, which is not what an exhausted, overstimulated and undernourished crowd had been waiting for.

Earlier, the Doors, the Who, Miles Davis and Joni Mitchell had all performed on a site where food and drink was running out and people were not sure how they were going to get home. All that was left was Cohen.

“It’s good to be alone, in front of 600,000 people,” Cohen said, strumming his guitar, before the opening lines of Bird on the Wire. As he sang, you could feel peace descend across the festival site and across the island. Where there had been anger, there was now serenity.

Cohen was born in 1934, in Montreal, Canada, and it was words more than music that first captivated him. An aspiring novelist, his life changed dramatically when he met Marianne Ihlen in 1960.

She was part of the bohemian community on the Greek island of Hydra, with no electricity or phone lines, a creative hub for artists embracing an alternative lifestyle. At that first meeting, she said, “When my eyes met his, I felt it throughout my body.”

Cohen was visiting Hydra after leaving Montreal, and was drawn towards the island’s beauty and isolation. He rented a house, wrote poems, novels and songs and visited regularly for the next decade, spending time alone, or with Marianne and her young son, Axel.

Their on-off relationship spanned much of the decade. Both started separate relationships in the 1970s, but they continued to write to each other throughout their lives. The two remained close until her death in 2016, when Cohen was also ill.

Suggested Reading

Jimi Hendrix, the guitarist who kissed the sky

“I’m just a little behind you,” he wrote to her in her final days. “Close enough to take your hand. I’ve never forgotten your love and your beauty.”

He met Suzanne Elrod in the 1970s and they had two children together, spending their time between Montreal and Los Angeles. Their daughter Lorca trained as a pastry chef in Paris, their son Adam is a musician, making music on the island of Hydra, in the same room where his father wrote so many songs.

Fans go on their own pilgrimages to visit the island in Cohen’s honour, or to seek the solitude that he had been so happy to find, or maybe in the hope of meeting their own Marianne. To many of these fans, it is Hallelujah, originally with 80-plus verses, that strikes a particular resonance. Written during a time of creative struggle, Cohen was exploring the idea that joy can come from a broken heart.

Columbia Records initially refused to release the song. They wanted something immediate and commercial; not an epic lament about the beauty of failure. It was only when Jeff Buckley covered the song on his 1994 album Grace – a version Cohen called “unimprovable” – that Hallelujah became Hallelujah.

Its writer spent much of the 1990s at Mount Baldy Zen Center in California as an ordained Buddhist monk, where he led a celibate life, taking the name Jikan, meaning “the silent one”. This meditative life was replaced by one of extensive touring throughout the 2000s, not by choice but on discovering that his manager had taken millions of dollars from his retirement fund.

After not touring for 15 years, he performed around the world, including the Pyramid Stage as the sun set at the 2008 Glastonbury Festival. “We started this tour three years ago,” he told an audience in Los Angeles in 2010. “I was 73 then – just a kid with a crazy dream.”

He enjoyed his reputation as the poet laureate of gloom. His fans love his humour, his cheerful self-deprecation, his gritty gentleness, his ability to make sense of the brittleness of the world.

Leonard Cohen died at the age of 82. He’d had a fall in his home in the evening, and died in his sleep. His death was a day before Donald Trump became president of the United States of America for the first time and just months after the passing of Marianne Ihlen.

Throughout his career, Cohen showed the grace that he offered in the early hours at that special night on the Isle of Wight, a festival that is now thought of, partly due to his performance, as the British Woodstock.

In those moments, he showed how you can perform, how you can exist, by taking things slowly, doing things your own way, being an assured, meditative, calming voice that people could turn to, and always will.