“Are you photographing me for some reason?” Doris Lessing asks the journalist opening her taxi door for her.

“Have you heard the news? You’ve won the Nobel prize for literature!”

“Oh, Christ,” Lessing says, shooing away the gathering cloud of reporters and photographers. In the archive news clip from October 2007, she cuts quite the figure, a scarf tied around her hair, her son next to her holding a net of onions and an artichoke.

Before long, Lessing warms to her audience and gives them what they are there for. “I’ve won all the prizes in Europe, every bloody one,” she says, “so I’m delighted to win them all… it’s a royal flush.”

Lessing, who turned down the opportunity of a damehood in 1993, describing it as “a bit pantomimey,” had first been tipped to win the most prestigious award in literature 40 years earlier. “I think they were probably thinking they’d probably better give it to me now before I’ve popped off,” she said.

An author who spent her life writing about colonialism, communism, and women’s sexual lives had perhaps been too intimidating to a body that had rewarded only 10 female authors previously. Lessing, now aged 88, was as indifferent to the prize money (the equivalent of around £1.9m today) as she was to the acclaim: “A lot of money for an old lady who doesn’t need much.”

She was unable to attend the award ceremony in Stockholm, so her son Peter, who claimed to never have read a single book his mother had written, attended instead. Lessing stayed at home in her West Hampstead terrace as royalty and fellow Nobel winners gathered to celebrate her literary achievements.

Lessing grew up on a farm in 1920s colonial Rhodesia, where she described “just thinking about how to escape, all the time.” Her love of reading kept her going: “Books arrived in great brown paper parcels, and they were the joy of my young life. A mud hut, but full of books.”

In 1942, with the married name of Doris Wisdom, she made the decision to leave her husband and two young children in Rhodesia. She was 24 years old.

“They would understand later why I had left. I was going to change this ugly world, they would live in a beautiful, perfect world where there would be no race hatred, injustice, and so forth,” she later wrote. Her daughter Jean was given to a neighbour, who had longed for a daughter all her life. “I did not feel guilty about this then, and do not feel guilty now.”

Suggested Reading

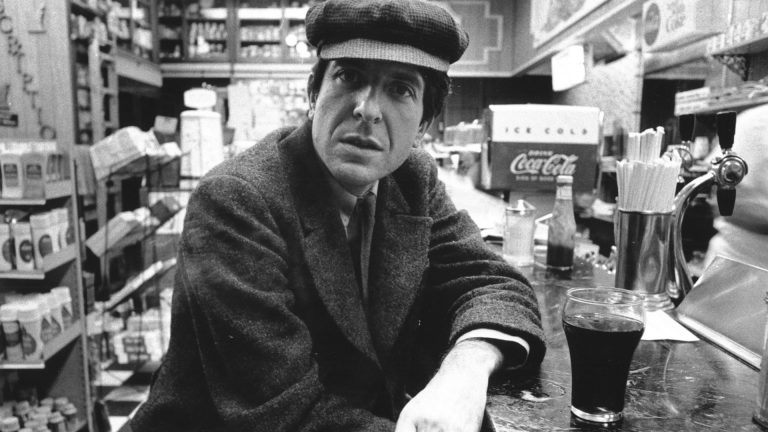

Leonard Cohen, the poet laureate of gloom

In 1948 she left South Africa, with her husband Gottfried Lessing, who she married months after leaving her family. He was an intellectual and committed communist. They married out of necessity: “It was my revolutionary duty to marry him.”

The Lessings arrived in England, but the change of scenery did not improve on an unhappy marriage. Her frustrations and anger led to a rawness in her writing, which was revolutionary in itself. In her own memoirs and letters, she goes back to the feeling of being unwanted at a young age, particularly from her own mother: “What I remember is hard, bundling hands, impatient arms and her voice telling me over and over again that she had not wanted a girl.”

Living with her young son Peter in London, Lessing put her own pain into the characters she created and sold her manuscript, The Grass Is Singing, to Jonathan Cape. Published in 1950 and set in colonial Rhodesia, the novel follows Mary Turner, an isolated white woman trapped in a loveless marriage.

The literary presses bristled with excitement about the work of this new author. One critic wrote: “There is passion here, a piercing accuracy, a rare sensitivity and power… one can only marvel.”

This was followed with Martha Quest, a novel where the protagonist makes the same decision as the author, to leave her husband and child to pursue political and social freedom.

Among her greatest work, critics say, is The Golden Notebook, following Anna Wulf, a writer struggling to bring together political disillusionment, motherhood, love affairs and creativity, assigning a separate notebook for each of the four themes. It is thought of as one of the most influential and important novels of the 20th century and the novel that gave her an international audience.

Lessing, who died in November 2013, a few weeks after her son Peter, remains the oldest person to ever receive the Nobel prize for literature. The speech On Not Winning the Nobel Prize, read out on her behalf by her publisher at the Nobel banquet night in December 2007, marks one of the most significant literary contributions of her career.

Lessing wrote not about poverty, but literary poverty – what happens when eager minds are deprived of books. She made the case for books being a basic human right.

“Not long ago, a friend who had been in Zimbabwe told me about a village where people had not eaten for three days, but they were still talking about books and how to get them, about education,” she wrote. Regardless of the surroundings, no matter the level of poverty, a library can transform lives.

Lessing filled her own world with stories when she was growing up, just to survive. In adulthood, these stories helped her and millions of others to make sense of a rapidly changing world.

As she herself noted, “It is our stories that will re-create us, when we are torn and broken.”