The performance looks nerveless, yet it’s anything but. Ágnes Keleti begins her optional balance beam routine at the 1956 Olympics with her left hand on her left leg, the foot of which is stretched impossibly high above her head. For the next 90 seconds, she skips and pirouettes, bending and stretching her body so she resembles nothing less than the Spirit of Ecstasy, the symbol of style and grace to be found on the bonnet of a Rolls-Royce.

The routine wins her gold, one of four she collects in five days in Melbourne’s Festival Hall. She will be unable to take any of them home to Hungary, though, because the fear Keleti has felt throughout the gymnastics competition is not rooted in self-doubt, or concern about the qualities of her great rival, Larisa Latynina of the Soviet Union. She will later admit: “I had much bigger worries about the future of my country than I would do in the competition.”

Keleti had left for Australia with her homeland in turmoil. Weeks before athletes sailed down under, an uprising had erupted in Budapest, calling for Soviet withdrawal. The attempted revolution was quickly and brutally closed down, leading to thousands being killed or forced to flee their homes, uncertain whether they would ever return. As news filtered through to the ship on which Soviet and Hungarian athletes were sailing, fights broke out between the warring teams.

Tensions ran high during the Games themselves, especially in a men’s water polo semi-final between the two countries. Police had to prevent a riot in what became known as the “Blood in the Water” match, an aggressive encounter in which Hungary’s Ervin Zádor emerged from the pool with blood pouring from above his eye after being punched by a Soviet player.

The gymnastics arena had once been used for boxing, but the only fighting there was mental. Though Keleti saw the powerful Soviet team as “rivals, not enemies”, the feeling was not mutual. “She wasn’t very nice or very friendly,” Keleti said of the 21-year-old Latynina. “I never spoke one word to her… I only thought of doing my best, of showing what I had trained for.”

By the end of the events on December 7, Latynina had won four golds, a silver and a bronze. Keleti added two silvers to her haul, meaning a symbolic triumph by the narrowest margin. It would have been a remarkable achievement in any circumstances, but very few athletes have had to endure what Keleti went through in order to compete for her country.

She was born in Budapest in 1921 to Jewish parents, won her first national title at the age of 16, and was on course to represent Hungary at the 1940 Tokyo Olympics at 19 when the outbreak of the second world war saw the Games cancelled.

Suggested Reading

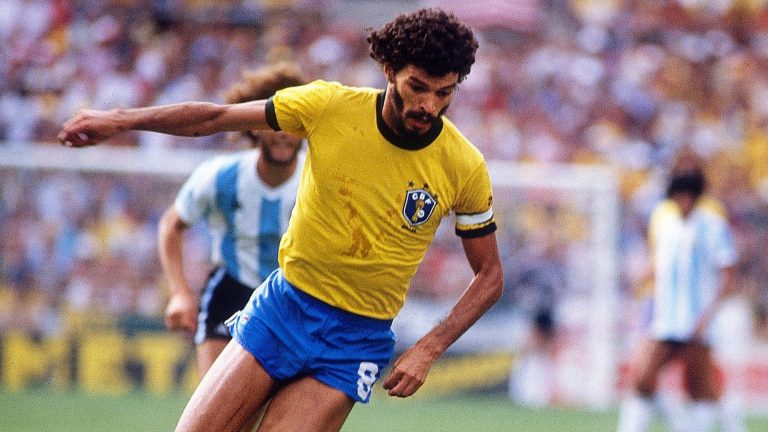

Sócrates, the beautiful game’s great romantic

Worse was to come. In 1941 she was forced to leave her gymnastics club because of the introduction of anti-Jewish legislation. To escape growing antisemitism she chose to flee Hungary, buying the identification papers of a non-Jewish girl of similar age to her. While most of her family were taken to concentration camps, Keleti used this false identity to create a new life, finding work as a maid in the countryside where no one knew her true identity.

Back in Budapest, when it was safe to return she was reunited with her mother and sister but was told the news that her father had died in Auschwitz. Determined but heartbroken, she had gymnastics to focus on. But her dream of competing in the hugely anticipated postwar 1948 London Olympics – the first Games for a dozen years – was crushed after she tore a ligament.

Still Keleti refused to give up. She persevered, she trained, she believed and in 1952 she was finally able to represent her country in her first ever Olympic Games. “I didn’t really think I could win anything,” she said years later. It was there in Helsinki she won her first Olympic gold, impressing the world with her athleticism, grace and musicality. “When I came to the competition I was completely calm,” she remembered. “When I entered the hall for my floor routine, all I felt was happiness.”

It was a far different feeling four years later. The fact Keleti was even able to set foot on a gym mat out in Melbourne was heroic in itself. To be confirmed as champion in four different events, helping Hungary finish fourth on the overall medals table, made her an Olympics legend.

When the 1956 Games were over, 40 Hungarian athletes, including Keleti, chose not to return home. She stayed in Australia, but despite her mother and sister joining her there, could not settle.

She did not attempt to qualify for the 1960 Rome Olympics – she would have been 39 in a sport where people often retire at the age of 20. Instead, she moved to Israel, where she combined coaching the Israeli national gymnastics team with working as a PE teacher. It was there she met another teacher and fellow Hungarian, Róbert Bíró. They made a life together, marrying in 1959 and raising two sons.

For the last 10 years of her life, she had returned to live in Budapest and for the last five had done so as the oldest living Olympic champion. She died a week before her 104th birthday, after being hospitalised with pneumonia.

“I wake up every day curious about the world,” she said, when asked about turning 100. “Curiosity keeps you young.”