Poland is barely an hour away by train or car from Berlin, and yet most Germans scratch their heads when you ask them the last time they visited their eastern neighbour. They would rather fly across Europe to their second homes in Mallorca or the Canary Islands. Meanwhile, the number of Poles living and working in Germany is decreasing as they see better job opportunities and higher growth back home.

There are several reasons for the froideur, and they reinforce each other. The past has re-emerged to poison the present, and the far right is exploiting it for all its worth.

I’ve visited Poland many times, by plane from the UK and elsewhere, but – crazily – this was the first time I’d gone across the border in all my years of living in Germany. Polish trains leave the German capital’s central station every two hours. Mine was comfortable, but hardly busy.

From the comfortable vantage point of the restaurant car (remarkably they still have a kitchen and cook dishes from scratch), I remarked at how flat the snowy landscape was, all the way for five hours to Warsaw. How easy, I pondered tastelessly, it would have been to invade.

It’s understandable that a country which ceased to exist for over a century, and was then attacked and brutalised and occupied from east and west by the Nazis and Soviets, refuses to forget. The German-Polish Barometer, a survey of Poles and Germans that has been conducted at regular intervals since 2000, shows that Polish attitudes towards Germans have hit an all-time low. Meanwhile, unlike its equivalents across Europe, the populist authoritarian Law and Justice Party (PiS) in Poland is not smitten by Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin remains an object of deep suspicion.

There are few votes to be won in being warm about Germany, and even fewer when it comes to Russia. On everything else in Polish politics, where identity politics has long been centre-stage, opinion is radically split. Poland is stuck in an ugly 50:50 culture war, and the prospects are for worse to come.

The curiosity is that this is a country that for more than a decade has enjoyed consistently high growth of 4% and over – an extraordinary performance, particularly when compared with the anaemic performances of Britain, France and Germany. Warsaw is booming; other big cities are booming. Polish entrepreneurship and innovation are regarded by investors as among the continent’s most impressive. The days of Poles seeking fame and fortune abroad are long gone.

The Polish divide is, in one respect, no different to elsewhere – urban-metropolitan, higher-educated on the one hand, and small town and rural on the other. The Catholic Church continues to play a pivotal role, just as it did tacitly during the Solidarity uprisings of the 1980s and the collapse of Communism. In the absence of anything else, it has sought to provide the societal glue; alongside that have come some of Europe’s most restrictive laws on abortion and LGBTQ rights.

With the best of intentions, Poland’s constitution has now unwittingly enshrined the split. Designed in the heady days of the early 1990s, it provides strong powers for both the president and government. The original aim was to prevent any single leader from accumulating too much power; instead, it has produced near-deadlock, with the far right Law and Justice Party (PiS) pitted against the mainstream conservative Civic Platform (now called Civic Coalition).

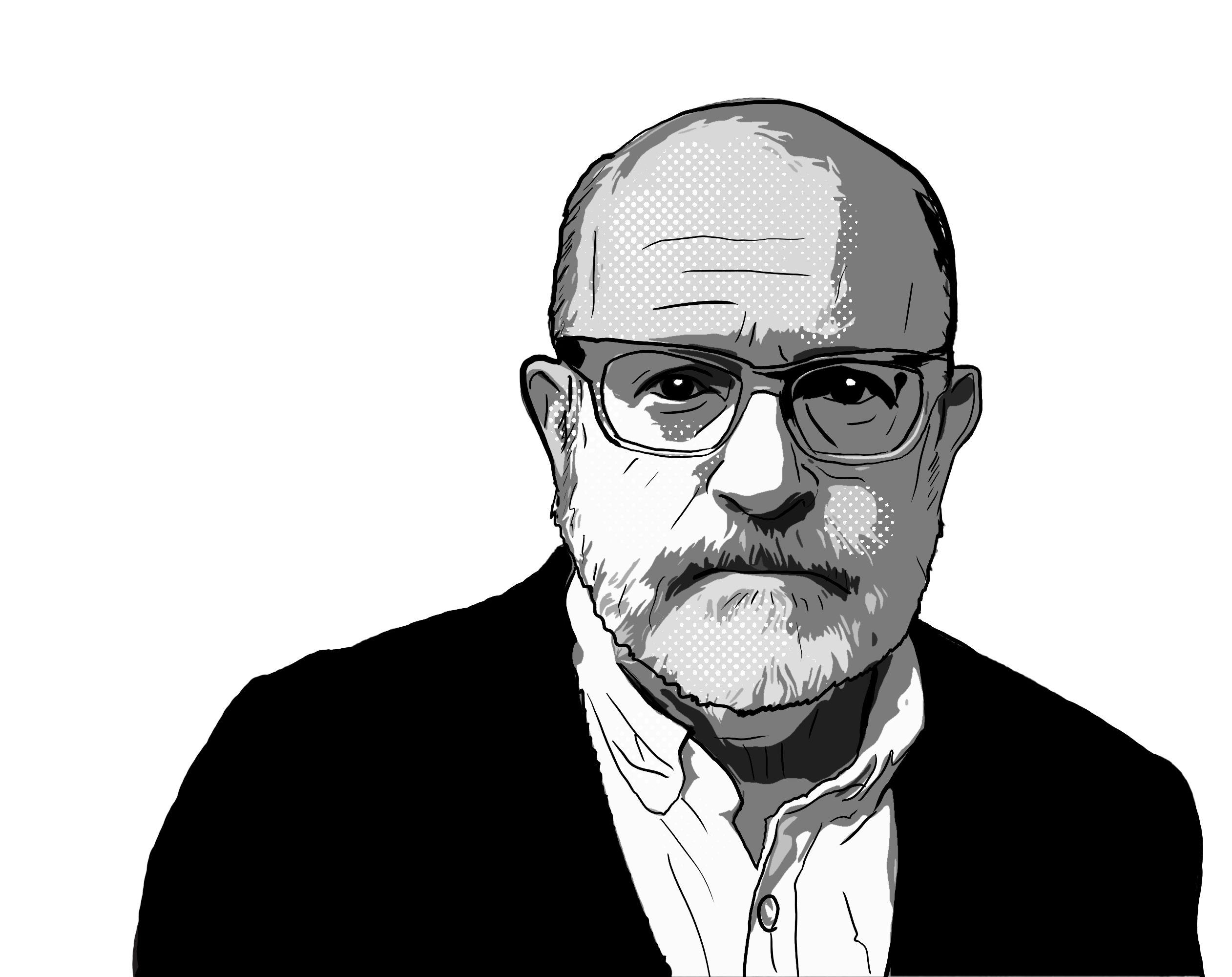

In the centrist corner is Donald Tusk. Having lost out in presidential elections in 2005 to the far right, he served as prime minister from 2007 to 2014, all the while having to fend off a presidency intent on blocking him. He made several attempts to change the constitution, but they failed to get the necessary super-majority in parliament. In 2015, in a foretaste of what was to come with Donald Trump I and Brexit, PiS won all levers of power and proceeded to sack anyone, anywhere who was remotely liberal.

Tusk went on to become president of the European Council for five years. The only Pole so far to have held high office in Brussels, he epitomises everything the anti-global populists loathe. In 2023, he returned as prime minister – only just, as only after the president tried and failed to engineer a different coalition – but in that time he has only managed to redress the balance slightly.

Last May it all went wrong, again. By a Brexit-style narrow majority of 51 to 49%, Poles opted for a historian and amateur boxer, Karol Nawrocki, as their president. Against the odds, Nawrocki defeated Rafał Trzaskowski, the experienced mayor of Warsaw, a centrist, and former MEP who speaks five languages. As is often the case, particularly in central and eastern Europe, big-city mayors do not translate nationally.

Nawrocki’s past is just a little colourful. The list of allegations accompanying him include whether he swindled an elderly man into transferring ownership of his apartment in the northern city of Gdańsk, to pimping at a luxury hotel at Sopot, a beach resort nearby. It is an assertion Nawrocki strenuously denies. He also has a record of football hooliganism. None of these seemed unduly to bother his base.

Suggested Reading

Poland, the most successful country in Europe

He instead portrayed himself as being at the vanguard of Polish identity, declaring that “historical politics” would play a key role in his presidency. The narrative is focused on his countrymen’s record as heroes and victims, on “defence of Polish dignity”.

On day-to-day politics, Nawrocki pledged to veto anything passed by parliament that he disagreed with; and in his first six months he has largely done that. He is sceptical, in the extreme, about plans to borrow 43.7 billion euros of EU money under the loans-for-weapons SAFE program.

He has also assembled an apparatus to carry out his own version of foreign affairs. This presents a dilemma for foreign diplomats in Warsaw, having to deal with two national security advisers, and doubles in most areas of policy.

While the prime minister has sought to bring Poland closer to the heart of EU decision-making, the president has aligned himself firmly to Donald Trump and MAGA.

The US administration did everything it could to help Nawrocki get elected, inviting him to the White House in the middle of the campaign. A few weeks later, he received formal endorsement via Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary – she of shoot-on-sight ICE infamy in Minnesota – when she visited Poland to attend a meeting of the Conservative Political Action Conference.

Like their counterparts from Germany’s AfD, like Nigel Farage, Poland’s far right politicians are warmly welcomed in Washington. They’re regulars at CPAC and other events, while the official Polish ambassador – accountable to Tusk and his foreign minister, Radosław Sikorski, struggles to gain access.

Within weeks of taking office as president last August, Nawrocki went to see Trump for a second time in quick succession. In a break with tradition, he invited no representative from the Polish foreign ministry or embassy to the meeting.

The American approach is set out for all to see in the recently published National Security Strategy. The document makes clear the intention of the US administration to weaken the EU and to embrace right wing nationalists in Europe, be they in power, such as in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Italy, or bidding for it, such as in France.

In Poland, the battle is set to intensify. Tusk and everyone around him are looking nervously over their shoulders as parliamentary elections must be held by November 2027 at the latest. Opinion polls suggested a consolidation of both organs of power by the far right. While Civic Coalition remains marginally ahead, its vote share would not be enough to get it over the line.

Two parties even more extreme than PiS would – if the numbers were reflected on election day – be likely to determine the outcome. One is called Confederation. When it first ran in the 2019 European Parliament elections, one of its leaders, Sławomir Mentzen, declared: “We don’t want Jews, homosexuals, abortion, taxes and the European Union.” He has since tried to distance himself from that statement, a little.

The other grouping is even more off the scale. It is called the Crown and is the personal fiefdom of Grzegorz Braun, who in December 2023 while an MP doused a menorah candle with a fire extinguisher during the annual marking of the Jewish festival of Hanukkah. Parliament, the Sejm, stripped him of his immunity and he is currently facing trial.

During his first court appearance, he said his action fell firmly within his parliamentary remit. He was still allowed to stand in the presidential elections last May, where the combined vote in the first round for Mentzen and Braun was almost 21%. Polls suggest those numbers have since risen further.

For Trump, such an outcome – a PiS president and prime minister, aided and abetted by conspiracy theorists – would overnight turn Poland into one of his closest allies. It would leapfrog the role of EU-saboteur currently played by Hungary, whose longstanding prime minister, Viktor Orbán, faces a possible defeat in elections in April (unless he manages to fiddle the vote). Orbán is regarded with affection in MAGA circles, but is increasingly seen as beyond his sell-by date.

Both sides know that Nawrocki must keep a certain performative distance from the White House. In a country whose identity is tied with notions of sovereignty, being seen as a Trump whisperer has its downsides.

Tusk presents himself as the last stand for liberal democracy. In echoes of Keir Starmer, he trims and he discards anything that might seem controversial. He also seeks to appropriate some of the positions of the populists, not least on immigration and issues of identity.

As a result, relations with Germany have deteriorated. The previous PiS government put reparations for damage caused by the Nazis’ occupation of Poland at the heart of foreign and European policy. Amid increasingly bellicose rhetoric, it commissioned a report that in 2022 calculated the compensation owed at €1.5tn.

Suggested Reading

Is Poland Europe’s literary giant?

Even though it was more than three times the size of Germany’s actual budget, the former government minister who led the work described it as “conservative”. The issue has continued to rumble into Tusk’s administration, with successive governments in Berlin insisting that the issue has long been legally closed.

All of this presents a dilemma for Friedrich Merz, who pledged to put Poland at the heart of his Europe policy, keeping an electoral promise to visit both Paris and Warsaw on the same day straight after his appointment last May.

The mood soured quickly, however, when Merz’s new government announced within weeks of taking office that it was introducing checks on all its borders, including Poland, and would send back any migrant who had arrived from neighbouring countries. Immediately the Polish far right sent self-declared “citizen patrols” to the Polish side of the border in a bid to stop them coming over.

Even though the actual numbers were smaller than they had been before, the optics were terrible. As the pressure on Tusk grew, he was forced to exclaim that “Poland’s patience is running out”. His government introduced tit-for-tat checks on its own side of the frontier, and while they have since been pared back on both sides, the bad feeling on the issue has lingered.

Tusk is hedging his bets, seeking stronger relations with Paris in an EU context and with London. Yet even here he has received setbacks, with Poland feeling shut out from important Ukraine meetings by the E3 (Germany, France and the UK).

In the mayhem of now, autumn 2027 feels a long way away. On the surface, Warsaw and the main cities seem to be thriving. Yet behind the scenes, some are wondering nervously about their fate. They have seen the difference between Trump I and Trump II, and they fear that a far right government holding all levers would be unrecognisable to anything that has come before.

One woman who had worked in central government, and has now taken a quieter job in a mayoralty, told me that when she left, she was hounded. “They not only kick you out, they also pursue you with lawyers on fabricated charges. I had to pay for my own.” She was fully exonerated, and her MAGA-style accusers eventually disappeared, but she received no apology.

Some of her friends have chosen to stay away from government, for fear of what might await them. That is the grim scenario. But there is another, one of thriving start-ups, young creatives and internationally engaged citizens. Its fate hangs in the balance, but on this occasion, Poland alone will be responsible for the outcome.

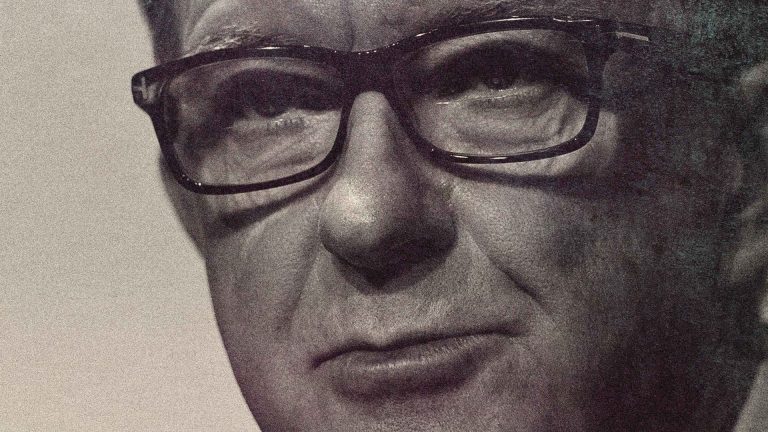

John Kampfner’s new book Braver New World: The Countries Daring to Do Things Others Won’t is published by Atlantic on April 16