Whatever you do, I remind myself, don’t get it out and read it on the bus. I was on my way from my home to the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, the Institute for Advanced Study, where I’ve been a fellow for the past year. For the previous few months, while scholars there were looking at the late Byzantine era, pragmatic philosophy or LGBT rights, I was engrossed in something grubby.

At the start of this year, I was commissioned by the BBC to do a one-hour archive special to mark the centenary of the publication of Hitler’s notorious book. It’s not often done, but it has to be done, to get a better sense of it.

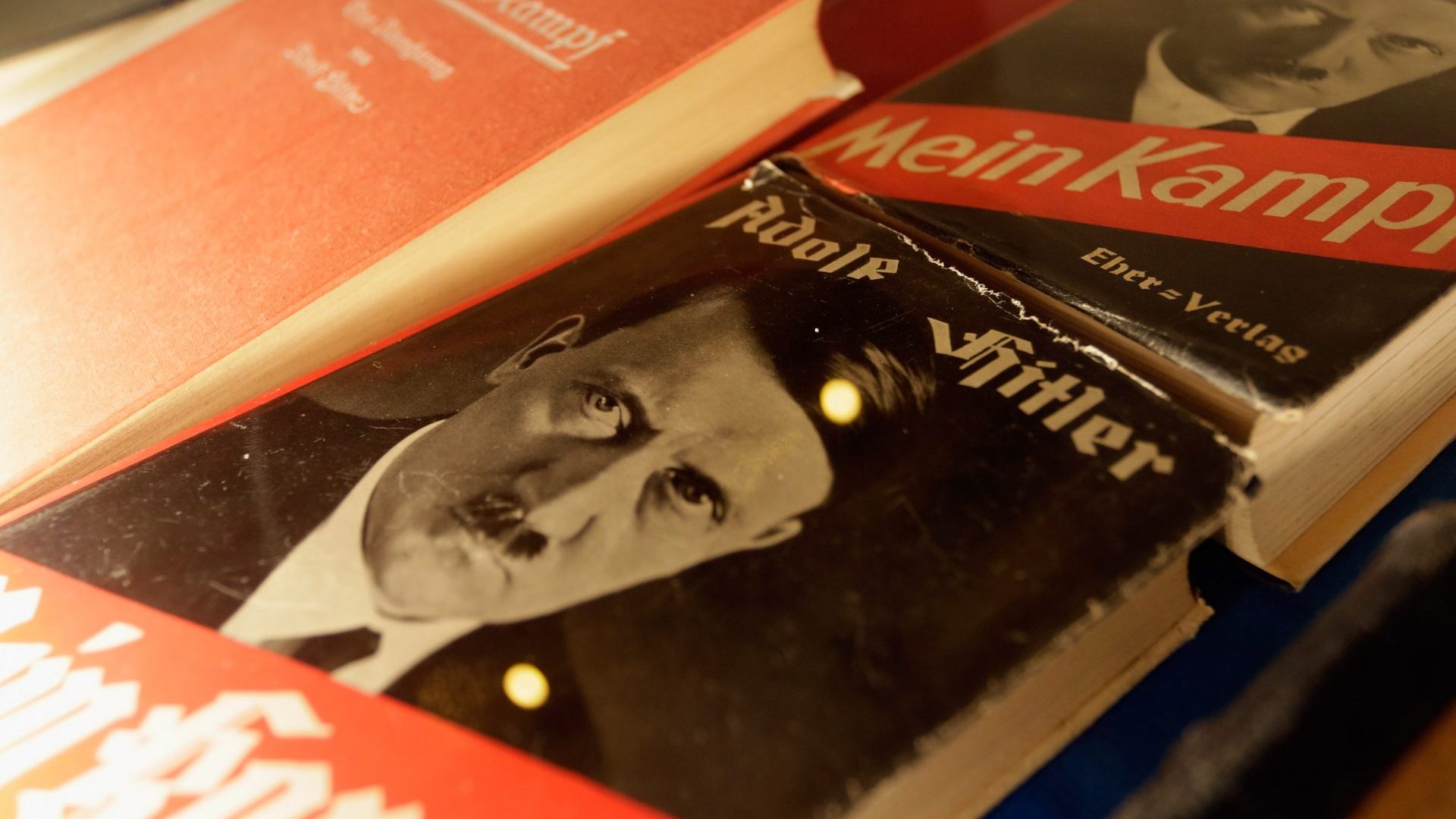

To research Mein Kampf is to engage in the art of subterfuge. When requesting interviews of experts, I put the letters “MK” in the subject heading. When requesting copies of the book, I didn’t fill out the normal online portal of the institute’s library – author, title, year of publication… I didn’t think it would make a very good impression. So, I went in person to tell them what I was doing. A few days later, I emerged with four hefty tomes – the original in German, an English translation from 1933 and, split into two volumes, the sanitised 2015 “critical edition”.

It was never going to be a straightforward assignment for me. My father escaped Czechoslovakia by the skin of his teeth in the summer of 1939. Several members of his extended family were killed in the concentration camps. He rarely spoke of his ordeal; I never got to ask him about my painfully awkward surname (the object of much ribbing as a schoolboy).

Before embarking on this assignment, I had never read Mein Kampf. Everyone knows the title of this book. But because of all that it’s come to represent, almost nobody says they’ve read it.

It took nerves of steel to plough through the more than 700 pages of this grubby work, which is what I did, 30 pages a night, with its endless distorted references to biology and race theory, with its warnings about miscegenation and the poisoning of good German blood.

When I told German friends about my project, most were horrified. Mein Kampf is something best left alone, banished to the outer reaches of “memory culture” scholarship. It may be referenced during classes about Nazi history at school, but it is not studied. It’s not hard to understand why, but I’m not sure that the taboo helps understand the past, let alone the present.

At the end of the war, the Americans and the German authorities used copyright as the best way of restricting circulation of the book. It could still be bought from antique shops. Yes, it was still shared in neo-Nazi cells. Plus, it was not uncommon for the later generations to find it openly displayed on the bookshelves of their parents or grandparents or hidden away in attics or cellars. But, as Germany embarked on its process of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, coming to terms with history, Mein Kampf effectively became a non-book.

I wanted to understand not just the content of the book, or the history, which is familiar: it was written while Hitler was in prison and then distributed as the ubiquitous text after he came to power in 1933. I wanted a better sense of how people have related to it ever since. My interviews focused not just on historians and scholars but included comedy and theatre performances. I planned to walk into a book shop and, with microphone in hand, ask for a copy of the book. Realising that this would look crass, I instead sat down and talked at length to the proprietors about the sensitivities.

With the copyright due to run out in 2015, a heated debate took place about what to do next. Would new versions emerge on the far right, and if so, how would they be dealt with? The decision was taken to publish a new version under the aegis of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich, with side notes added to every page, detailing distortions, falsehoods and pointing to the ensuing horrors.

Did that mean the job was done? In a narrow sense, yes. But what has struck me during my six months of research is that the world has moved on from Mein Kampf – and into a place of contemporary darkness.

Simon Strick, an expert on the alt-right at the University of Potsdam, says stamping on one book will not eradicate the problem: “Mein Kampf isn’t the one thing that you should be worried about, but there are a million agitational materials, videos, blogs, whatever, on the internet that articulate the same thing, and always have done so.”

Strick shows me on his laptop a series of YouTube videos. The first is an American one from 2018, in which the narrator laments the loss of the nation of his forefathers and its takeover by effete liberals, globalised metropolitans, and by immigrants. Over moody film of spectacular open landscapes, he declares: “As I see these carpetbaggers and these locusts come to harvest the fields my family ploughed for centuries, I feel, because it has been bred in my bones, the need to once again venture out into the wilderness to escape the leeches.”

Then comes a British video, of smartly dressed men dancing formally with well-groomed women over the words: “the indigenous people of Europe are becoming minorities within their own homelands.” Bloggers, vloggers, agitators borrow the themes of the 1920s and 30s but they don’t usually cite Mein Kampf directly. Perhaps they think it will taint them. Perhaps they think it’s no longer relevant or cool.

Voices such as these enjoy a huge following. In today’s fragmented online space, ideas that were previously seen as extreme or unacceptable can now, within a split second, be amplified by a world leader or a billionaire. They also receive an “intellectual” imprimatur. Just as Hitler had many philosophers, thinkers and political scientists to call on – think Houston Stewart Chamberlain or Carl Schmitt – so, Renaud Camus’s theory of the “Great Replacement” of a decade ago has led to a new crop of ideologues. They focus on the same messages as before – race, natalism, miscegenation, masculinity, encirclement, grievance, fake news, the “other” – but they have refashioned them for the contemporary era.

Suggested Reading

The ex-Nazis who got away with their past

In my radio programme, I use several clips from well-

known politicians. I quote Giorgia Meloni during a rally in 2017 (still in opposition and not yet prime minister), talking of high immigration as “ethnic replacement”.

Or this, from Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, telling an audience in July 2022 that it is fine for European peoples to mix with each other, but not with those arriving from outside Europe. “We are not mixed race,” he says. “We do not want to become peoples of mixed-race.”

Compare these with this sentence in chapter 11 of Mein Kampf, entitled “People and Race”: “Blood mixture and the resultant drop in the racial level is the sole cause of the dying out of old cultures.”

Or this from Donald Trump, on his Truth Social platform in late 2023: “Illegal immigration is poisoning the blood of our nation. They’re coming from prisons, from mental institutions, from all over the world. Without borders and fair elections, you don’t have a country. Make America Great Again! We must win in 2024 or we will not have a nation.”

As Chapter 2 of Volume 2, “The State”, says: “the poisonings of the blood which have befallen our people… have led not only to a decomposition of our blood, but also of our soul.”

Trump acknowledged the connection, only to dismiss it. During a campaign rally in December 2023, he said: “They’re destroying the blood of our country, that’s what they’re doing. They’re destroying our country. They don’t like it when I said that. And I never read Mein Kampf. They said, ‘Oh Hitler said that, in a much different way’.”

I’m fully aware that anyone cross-referencing modern-day populism with the 1920s and 30s lays themselves open to being denounced as simplistic or plain wrong. No two political movements or historic moments are ever exactly alike. Words don’t inevitably lead to actions. Yet for all the efforts to eradicate the ideas in this infamous book, some of them have returned into the heart of global politics.

Hitler remains off-limits. Or if he is discussed, it is sometimes in a jokey, mischievous manner. Remember the “fireside chat” between Alice Weidel, the leader of the AfD, and Elon Musk? I listened to all 75 minutes one January evening, live, as the world’s richest man conversed with Weidel, who heads the extreme right wing party he would love to see running Germany.

With encouragement from Musk, Weidel said that Hitler’s most important error was, as the second part of his party’s name suggested, that he was an ardent socialist.

Musk: Yeah, very much so.

Weidel: Yeah.

Musk: They nationalised industries like crazy.

Weidel: Absolutely!

She concluded: “He wasn’t a conservative. He wasn’t a libertarian. He was this communist, socialist guy.”

Banning Mein Kampf, the spirit of Mein Kampf, has turned out to be harder than we all realised.

Othmar Plöckinger, author of a landmark book on Mein Kampf and one of the editors of the critical edition, tells me: “Mein Kampf was a product of thinking that was much older than the book itself.” Contemporary far right politicians, he says, “don’t need Mein Kampf to despise democracy and they don’t need Mein Kampf to think in a racist way.”

Strick puts it even more starkly: “Mein Kampf is not special. There are a million different versions of the same material, the same ideology out there.”

Just as Hitler recycled pre-existing material, so his odious book is being refashioned for our times. It’s part of a continuum.

His ideas have always been there, and they’ve never gone away.

John Kampfner is an author, broadcaster and commentator whose most recent book is In Search of Berlin, The Story of a Reinvented City