One day, someone will write the definitive thesis on the connection between Instagram selfies, avocado on toast and far right populism. This combination is ever-present in many of the world’s most visited cities – from Rome to Budapest, from Buenos Aires to Bratislava.

Within weeks, Prague could be added to the list, except that the tens of thousands of people who take weekend breaks to admire its beauty, art and beer would have no idea that anything has changed. Such is the difference between 21st-century authoritarianism and 20th-century dictatorship.

The country, which (as Czechoslovakia) first tasted independence under the inspired inter-war leadership of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and which shook off Communism in 1989 thanks to Vaclav Havel, is on the verge of inaugurating a local oligarch propped up by motorists, assorted far-right weirdos and Putin sympathisers.

The Czech Republic of recent times has been a poster-boy for constructive engagement in the European Union and NATO and one of the staunchest supporters of Ukraine. And yet could imminently join several of its neighbours on the dark side. I say “could” because, while it’s likely, it’s not yet certain.

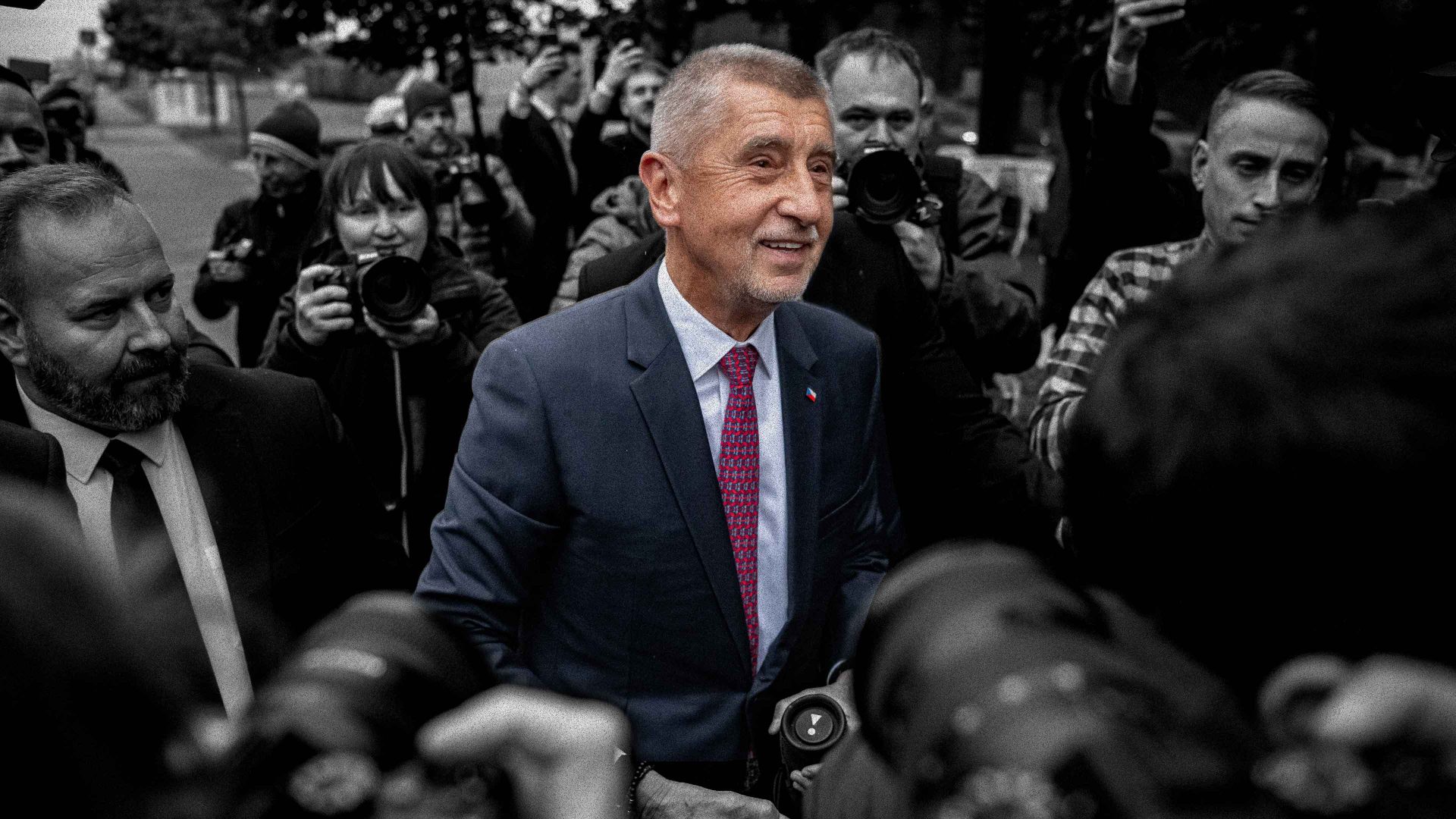

A quick recap: at the start of October, a government that had been dealing competently but unspectacularly with the usual mix of problems – cost of living, immigration, housing, defence and climate – was given the thumbs down in parliamentary elections. A third of voters opted to revert to Andrej Babiš, an old-timer who has already served as prime minister between 2017 and 2021.

Babiš’s party ANO translates to ‘Yes’, but is also an acronym for Action of Dissatisfied Citizens, a classic case of someone who has profited from the Establishment setting himself up as a foe of the Establishment. Heard that one before?

Another similarity with the man in the White House is that it’s all about business. A Slovak by birth (not that it mattered in those days, as it was the same country), he joined the Communist Party in his mid-20s when he started working for a state-controlled trading company.

He was recently outed by the Slovak National Memory Institute as having been an agent for state security service (StB). Babiš denied this, and in the end, with the ‘help’ of Slovakia’s hard right government, all sides agreed to disagree.

This episode is typical of Babiš’s career: money made from political connections, clientelism and a business savvy learned in the winner-takes-all immediate post-cold war years.

In 1993, he took over a company called Agrofert – a subsidiary of what originally was the trading company, Petrimex, turning it into a huge agricultural, food processing and chemical conglomerate. Agrofert bought various media outlets. And it received huge subsidies from the European Union. Then he went into politics. Again, heard that one before?

The thing about Babiš, as a seasoned observer told me in one of Prague’s ornate cafes, is that “he is eminently flexible. He’ll do whatever is good for his business interests”. ANO has been described as “the political department of his company”. He has been alternately a liberal, a leftist and a rightist, the ultimate pork barrel opportunist who promises everything to everyone – especially pensioners like him (he is 71 years old). His election campaign had little content; much of it was feel-good entertainment, and it seemed to work.

Unlike Viktor Orban, next door in Hungary, he is not ideologically pro-Kremlin or pro-China. Orban is a guru to MAGA, the real deal in Washington when it comes to the culture wars and the theory of the Strong Man. As the head of an NGO said to me, Babiš, by contrast, “is like tofu. You must add flavouring to get any taste”.

Which is where the small parties come in, and where the politics shifts from the disconcerting to the dangerous. To achieve a majority of the 200 seats in the lower house, Babiš has struck a deal with two smaller parties.

Freedom and Direct Democracy (its acronym is SDP), was founded just over a decade by a man with a half-Japanese and half-Korean father and a Czech mother. After being brought to Prague aged 10, Tomio Okamura had a liberal international education and an unremarkable early career.

Suggested Reading

Estonia, the country that’s doing digital ID cards right

As vice-president and spokesman for the Association of Czech Travel Agencies, he is remembered by journalists as being easy-going and not remotely extreme. He then came to prominence as a judge in the Czech version of Dragon’s Den. Then, apparently, he saw a market opportunity in the first populist wave of the 2010s.

Though it has so far been hard to prove Russian funding for his party, Okamura has consistently peddled Kremlin narratives – calling for a referendum on leaving both the EU and NATO. Shortly after the recent election, he became speaker of parliament. One of his first decisions was to have the Ukrainian flag removed from outside the building, where it had hung in a gesture of solidarity since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

Motorists for Themselves – a post-woke party name de nos jours – were founded in that same year, and over the past three years have seen their support rise. While they share much common cause with the SDP, the Motorists are focusing primarily on attacking the EU’s Green Deal.

Together, these two smaller parties received 15 per cent of the popular vote and have just over that share of the seats in parliament. They know Babiš needs them, and they will push him further to the extremes.

One of the most immediate decisions will be the composition of the cabinet. The Motorists originally demanded the foreign ministry for their leader, Filip Turek. A week after the election, a liberal investigative website, Denik N, published a series of Facebook posts that Turek thought he had deleted. In these posts, he referred to Barack Obama using a racial slur, made disparaging racial remarks about Meghan Markle and mocked a Romani girl burned in a 2009 neo-Nazi attack. Some of the social media posts he has apologised for; others he has denied authorship of.

In 2024, Turek won a seat in the European Parliament. During the campaign, several old photos of him were circulated online, including one where he wore a golden helmet with a symbol used by the former Greek neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn, one where he appeared to give a Nazi salute from a car, and one featuring a candlestick with a swastika. Perhaps because of the large number of accusations against him, he was proposed instead for the environment portfolio.

The foreign minister instead seems to be heading towards another senior Motorist, Petr Macinka. He turned up for a meeting with the president in early October in a massive Ram 1500 pickup truck, to signal his opposition to the EU’s demand that all vehicles with combustion engines be banned by 2035.

If the Motorists and SDP get their way, climate policy is set to be thrown out of the window. In the most important areas of foreign policy, on Russia/Ukraine and on China, the Czech Republic could also be on the verge of a 180-degree turn. Its neighbour and younger brother, Slovakia, did the same when Robert Fico returned to power in 2023, forming a rebel alliance in the heart of the EU with Orban. What happens in Prague, however, matters more.

The Czech government, which is still being run by the moderate Petr Fiala until the new one is sworn in, has been defiantly critical of China and staunch in its defence of Ukraine. The moral lead has been set by the president, Petr Pavel.

In July, Pavel took a detour at the end of a working trip to Japan by going to India to meet the Dalai Lama to personally congratulate him on his 90th birthday. That sent relations with Beijing into freefall. The Czech Republic has hosted more Ukrainian refugees per head than any other country (up to 400,000 out of a population of 11 million) and is on course to send 1.5 million artillery rounds to Kyiv.

All that is set to be reversed. Unless Pavel refuses to allow the government to take over.

Under Czech law, public officials are prohibited from engaging in business activities or holding positions in companies that could benefit from government decisions. It also specifically bans politicians from owning media outlets or companies that receive public subsidies or investment incentives.

Pavel has repeatedly invited Babiš to explain to the public how he will avoid conflicts of interest. Babiš has told Pavel he will sort things out once he is in post – and as everyone knows, once inaugurated he would hold all the cards.

The standoff has lasted several weeks; it could go on for longer, even into the new year. One option Pavel has would be to appoint a technocratic government, but that would only be an interim solution, and new elections would then have to follow.

Another option would be to invite Babiš to form a more centrist administration with mainstream parties, but that would not solve the business-interest problem. In any case, they would be extremely reluctant to work with him, as during the outgoing parliament, he and his colleagues did everything they could to undermine the workings of the chamber.

Who will blink first? The paradox of the Czech situation is that the country isn’t doing badly. The economy and standard of living are comparatively strong. Democratic checks and balances are also reasonably intact.

Unlike Slovakia, the Czech Republic has an upper house, the Senate, which isn’t in the hands of the far right. It has an independent audit office and constitutional court, and an active civil society.

The only problem is that this has been said before in other countries, not least the United States. Countries remain functioning democracies – until they’re not.

I ended my visit to the Trade Fair Palace, a 1970s brutalist building that is home to the national gallery. On its third floor is a permanent exhibition to the art and culture of the era between 1918 and the arrival of the Nazis in 1939, the Masaryk era.

The final room contains a cycle of works called Fire by the artist Josef Čapek, who painted them in response to the growing threat of fascism. Čapek was arrested for dissent by the Gestapo on September 1, 1939 and deported to a concentration camp. He died in Bergen-Belsen shortly before the end of the war; his remains were never found.

The picture I found most striking is of a woman, hands in the air in entreaty, as a building, presumably her house, is burning.

John Kampfner is the author of In Search Of Berlin: The Story of A Reinvented City