If 2025 was about defending Ukraine, 2026 will be about defending Europe, or at least the Europe we have known. Thanks to the open alliance between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, the unpalatable fact is that liberal democracy is under attack as never before. Indeed, this could be its final year.

“The dark forces of repression are on the march again. We are Russia’s next target. We are in harm’s way.” In the centre of destroyed and divided Berlin, the centre of two world wars, the centre of the cold war, this was the message in early December of Nato’s secretary-general, Mark Rutte, to Europe’s diplomatic establishment.

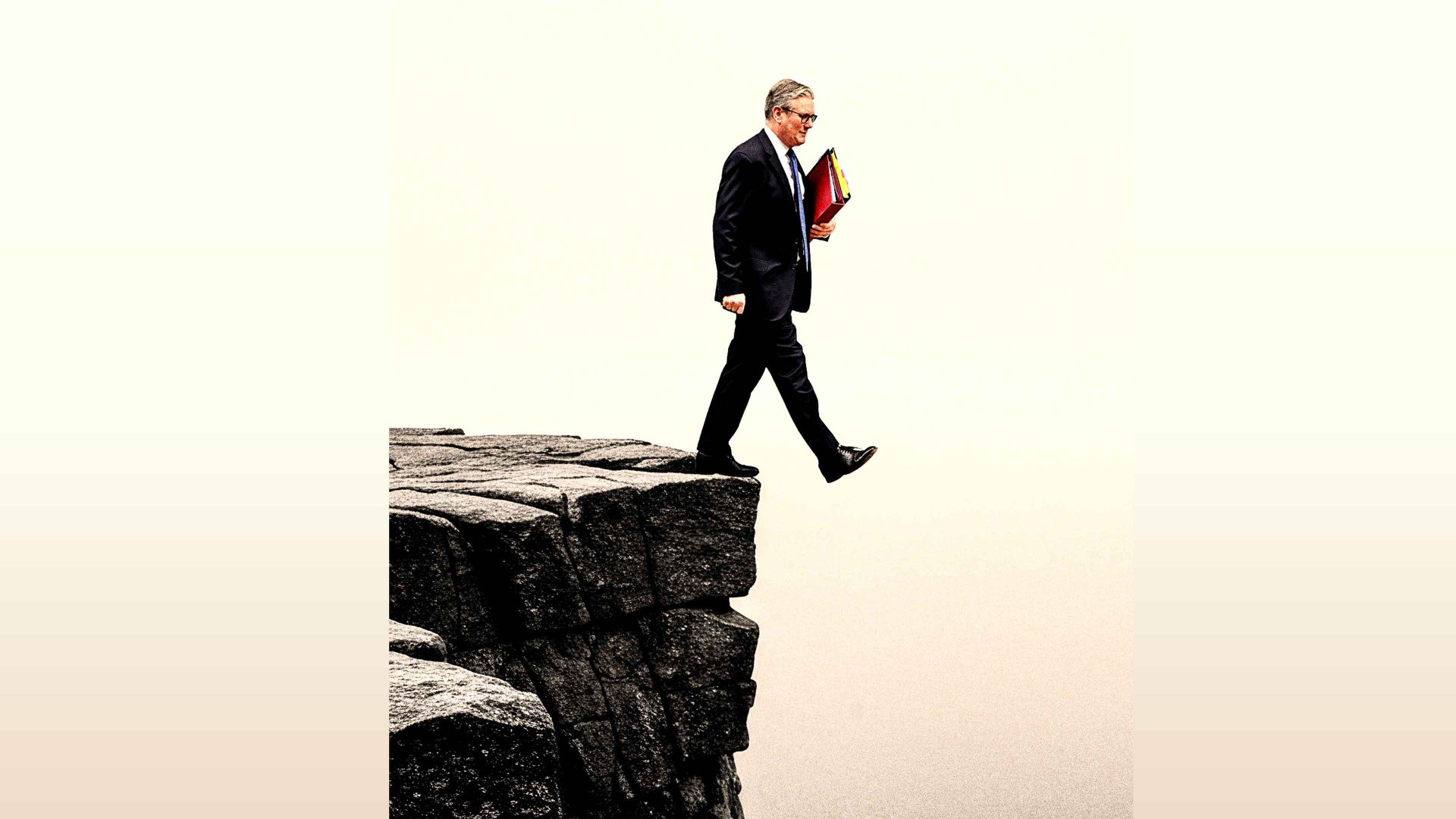

Rutte has acquired a taste for dramatic rhetoric. Wherever he goes, he warns national leaders that if they don’t step up, and quickly, Europe will not be able to withstand a Russian invasion. Indeed, he talks of the continent being already at war, pointing to the many hybrid attacks the Kremlin has mounted. But is anyone listening?

The answer is: some are, many are not. Perhaps it is the human condition to look the other way, but it is proving fiendishly hard to get across to most of the public, let alone the politicians, the extent of Europe’s vulnerability in the face of the twin threats from east and west.

An air of fatalism is growing, and a combination of denial and paralysis is taking hold. A commentary in the conservative newspaper Welt by one of its senior editors shortly before Christmas stated: “Ukraine will lose the war against Russia. This is something the Europeans must admit, even if it is painful. What matters now is trying to prevent the worst.” Just hours earlier, EU leaders had abandoned plans, which had been pushed hard by German chancellor Friedrich Merz, to requisition Russia’s frozen assets and put them at the disposal of Ukraine. A further credit line of €90bn was opened to the Ukrainians to keep their resistance afloat, but there was no disguising both the divisions at the heart of Europe and the loss of will to confront Putin.

It seems probable that some form of tawdry deal will be foisted on Volodymyr Zelensky, one that de facto gives the Kremlin the districts of eastern Ukraine that it grandiosely annexed into its constitution, even areas that it has yet to occupy militarily. What would then follow would probably be the steady strangulation of Ukrainian independence, with elections – heavily infiltrated by Russian disinformation – leading to a post-Zelensky figure more amenable to Moscow. Like the old days.

In Berlin, the city that now feels like the centre of this new cold war, nobody in government will publicly admit to any of these scenarios. Privately, however, officials are candid about the extent of the threat.

It was all set out from the start, but few fully understood the warnings at the time. Barely weeks after Trump’s second-term inauguration, his vice-president, JD Vance, used his appearance at the Munich Security Conference in February 2025 to attack European democracy, while praising the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and other far right parties across the continent. Since then, the US administration has been consistent. Deal with mainstream leaders if you have to, but strengthen support for their opponents where you can.

The recent US National Security Strategy codifies the shift. “American diplomacy should continue to stand up for genuine democracy, freedom of expression, and unapologetic celebrations of European nations’ individual character and history,” it writes. “America encourages its political allies in Europe to promote this revival of spirit, and the growing influence of patriotic European parties indeed gives cause for great optimism.”

It is there in black and white: in favour are parties that seek to destroy institutions that were established after the second world war, and the values that underpin them. The most hated of them all is the European Union, which is seen as a liberal woke project inimical to the Trumpian world view. At the last count, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia have fallen into the Maga (and Kremlin) camps. Others are expected to follow. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni straddles both sides.

The most curious recent case is that of Belgium, whose prime minister stood in the way of the assets deal that could have thrown Ukraine a longer-term lifeline. He started out on his own, gradually picking up support along the way. How did the leader of a small nation state that seldom has a functioning government and is not known for its clout in EU corridors turn things around in Moscow’s favour? Speculation is rife.

The French elections will be in the spring of 2027, with the prospect of the National Rally (RN) finally winning the presidency. Relations between the RN and Maga have strengthened considerably. Nigel Farage already celebrates his proximity to his American far right counterparts.

The party where the links are closest both with Putin and with Trump is the AfD. Earlier this month, one of its senior figures was formally received in Washington for the first time. After a meeting at the state department, foreign affairs spokesman and deputy chair of the AfD’s parliamentary group, Markus Frohnmaier, was an “honoured guest” at the annual gala of the New York Young Republican Club. The club likes to use the slogan “AfD über alles” – a play on the old Nazi anthem. Or as it put it in another statement: “As the German Volk suffer the political, economic, and social consequences of the failed liberal order, their government has repudiated its carefully cultivated reputation for embracing human rights in favour of a sinister regime of censorship and repression.”

During 2026, Germany’s mainstream consensus will be tested more severely than at any time. The crux will be elections in September in the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt, where polls put support for the AfD at 40%. If it maintains that level of popularity, it could seize control of a region for the first time.

Some in Merz’s Christian Democrats (CDU) are lobbying for the removal of the so-called firewall, which precludes formal contacts, less still coalitions, with the AfD. They argue that such is its popularity, it is no longer democratic or feasible to keep the party in the wilderness. That view is shared by some business figures, who suggest that in any case Germany could do with some Maga-style shock therapy.

Merz is subjected to relentless attacks from left and right, for being both too conservative and too ready to compromise with his coalition partners, the Social Democrats. The bellicosity in much of the national discourse is new and more in line now with the US and UK as mainstream media emulate the binary fury of social media platforms.

In the face of multiple threats, Merz is showing a determination that has eluded many of his European counterparts. The re-arming and modernisation of the Bundeswehr, the armed forces, is gathering speed. With half a trillion euros for critical infrastructure and at least as much available for the military, the government is starting to act. By 2029, it is estimated that Germany will be spending twice as much on defence as the UK.

Yet Germany and Europe are a long way from being able to defend themselves on their own – and it is in question whether they will ever be able to do so without the traditional support of the Americans. Russia is outspending Europe in all areas, from drones and new technology to tanks and artillery shells. It is not deploying its most sophisticated weaponry in Ukraine, saving it rather for potential combat elsewhere.

Not all is lost. Opinion polls show a mixed picture. Many Germans have acquired a respect for the resilience of the Nordics and Baltics, and particularly the notion of “total defence”. The re-introduction of military service – albeit initially more voluntary in nature – is not as unpopular as might have been expected.

But will any of this new-found steel hold? If a supposed ceasefire is enforced on Ukraine, the Putin-Versteher (Putin sympathisers), who have gone quiet in recent times, will come out of the woodwork suggesting that Germany and Europe should abandon their commitment to re-arm. Just as in the 1990s, they will talk of a “peace dividend”.

There are still glimmers of optimism. Merz knows he must deliver on his promises radically to reform the economy and improve living standards. The two main parties, CDU and SPD, will stand or fall together. They could yet pick away at some of the AfD’s support. Then there is the hope that Maga might sink further into acrimony, that all is not well, mentally and physically, with Trump, that the Democrats might start fighting back. And among all of that is the issue of whether Putin and Trump’s world views are fully aligned, or whether fissures might emerge.

In a series of recent discussions with German security officials, I have repeatedly asked one question: how far could Russia go militarily in Europe before it would no longer be in America’s interests to turn a blind eye? Nobody I have spoken to says they know. The answer could emerge in the coming 12 months.