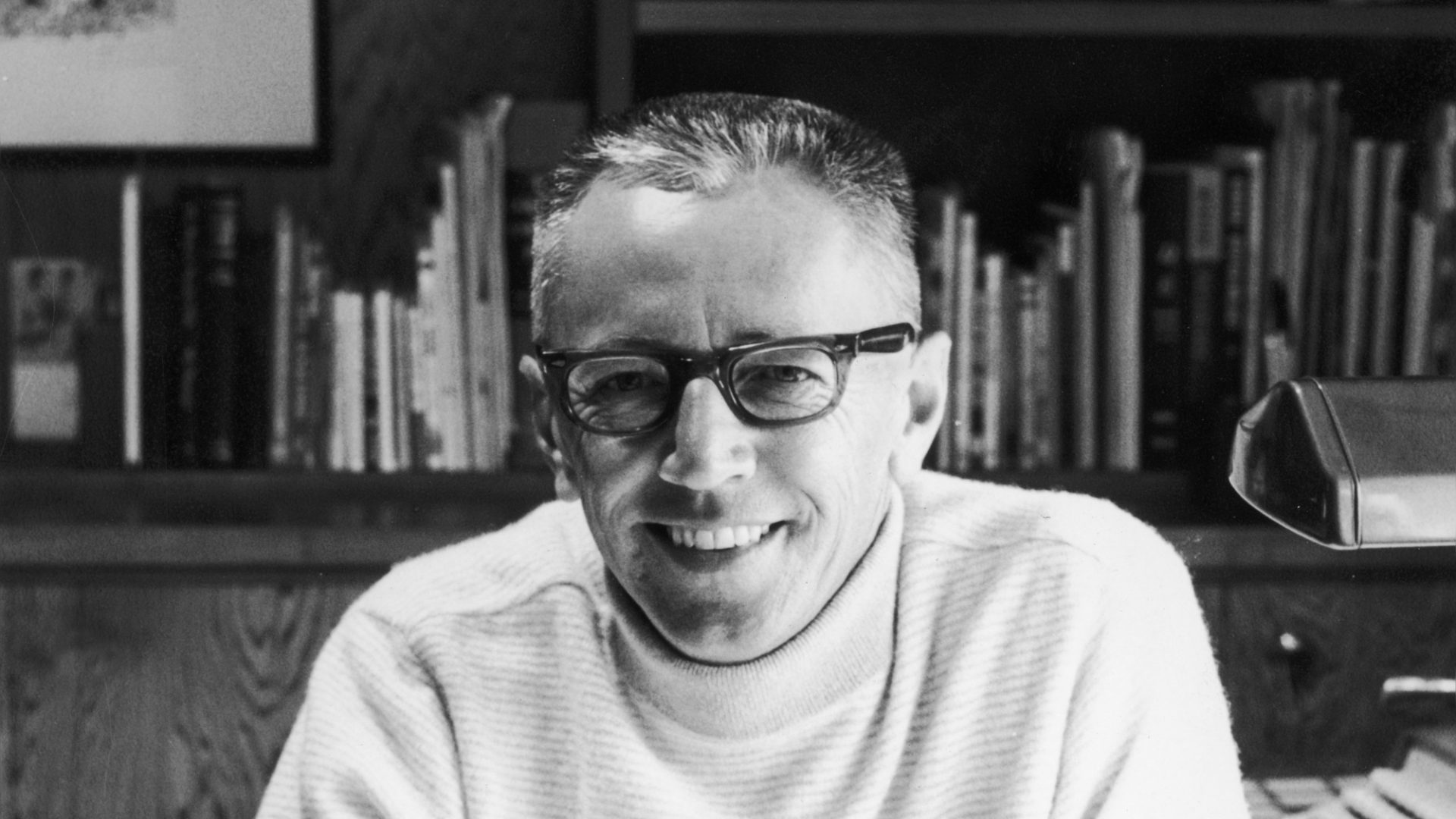

November 26, 1922 – February 12, 2000

Two children sit on a kerb. They look up as another boy walks past.

“Well here comes ol’ Charlie Brown. Good ol’ Charlie Brown,” one says to the other. “How I hate him!”

Those reading this new cartoon strip, quietly appearing in seven newspapers across America on October 2, 1950, are meeting the world of Peanuts for the first time. For the first two weeks, there are only four characters: Charlie Brown, his friends Patty and Shermy, and his dog, who by November we learn is called Snoopy.

Charles Schulz fell in love with cartoons while reading Sunday newspapers with his dad. It was Carl, a barber from Saint Paul, Minnesota, who first got his son in print when he wrote a letter to Ripley’s Believe It or Not! comic listing the range of objects their family dog Spike had eaten: “All these things have been swallowed whole and digested.” The letter is accompanied by the 14-year-old’s drawing of Spike.

Charles was an only child, close to both of his parents. He was tall, skinny and shy, and went through high school without ever having a date. He was happy in solitary pursuits – walking, reading and, crucially, drawing.

When his passion for cartoons and cartooning revealed itself towards the end of his school years, it was his mother Dena who told him about Art Instruction School, where students took lessons by post, sending in their drawings and receiving written feedback from tutors who were often professional artists. The course cost $170, expensive for his working-class parents, but here was a passion worth pursuing and funding.

Drafted in 1943, a 20-year-old Schulz headed off for basic training just as his mother was diagnosed with cervical cancer. Her death devastated him, and despite Charles being promoted to staff sergeant and ultimately leading a machine-gun squad, familiar feelings of being on his own took over. “The army taught me all I needed to know about loneliness,” he said.

At the end of the war, Schulz returned home to live with his dad above the barber’s shop. He got a job teaching at his old art school, and was able to spend his free time focusing on the type of cartoonist he wanted to be.

His feelings of being isolated as a teenager, his experience of war and the loss of his mother helped him pour his sadness and self-doubts into the characters he drew. In 1947, his single-frame comic Li’l Folks started to be published weekly by a local newspaper. Expanded to a four-panel format, Li’l Folks was picked up by United Feature Syndicate, who would place it in newspapers across the US, and later the world.

They changed the name of the cartoon, much to Schulz’s disapproval. “Although I have always resented the title Peanuts which I was forced to use – and I’m still convinced it’s the worst title for any comic strip – it probably doesn’t matter what it is called so long as each effort brings some kind of joy to someone, someplace,” he said.

Suggested Reading

Asma Jahangir, the woman who would not be silenced

Buoyed by a trip to New York to conclude the deal with UFS, Schulz returned home and proposed marriage to a female friend. “When she turned me down and married someone else, there was no doubt that Charlie Brown was on his way,” he said. “Losers get started early.” But months after the first syndication of Peanuts, Schulz married divorcee Joyce Halverson and adopted her daughter. The couple went on to have four more children, and, day by day, his other family grew too as new characters were introduced into the world of Charlie Brown.

There was a part of Schulz in all his characters, he said. “Charlie Brown is my wishy-washy and insecure side. Lucy is my smart alec side. Linus is my more curious and thoughtful side. Snoopy is the way I would like to be – fearless, the life of the party.”

Peanuts had all of that. The strips are inventively comic, but it is the tones of uncertainty and melancholy that made them stand out from the rest of what was known in America as “the funny papers”.

They still might not have become a phenomenon were it not for Schulz’s fearsome work ethic and control. He drew seven Peanuts comics a week for the half-century until his retirement in 2000, which amounted to 17,897 comic strips, every single one drawn himself.

No other person ever drew any of the characters, coloured them in or contributed a storyline. It was his creation, his gang, his universe.

“I think of every idea. I draw every strip, I letter every word because this is what I do. This is my life,” he said.

Schulz revelled in the bittersweet nature of holidays, and Peanuts included Valentine’s Day storylines from the early days, setting the universal themes of hope, fragility and rejection. Charlie Brown always thought that the next Valentine’s Day would be different… but it never was.

Peanuts characters started appearing on greeting cards and toys in the 1960s – nothing was licensed without the approval of Schulz. Anything in which his characters appeared had to remain faithful to his vision. Television films enhanced the brand.

Schulz loved that the world he had created was embraced by the lonely, that his characters helped people through hard times, saying proudly: “People who are sensitive need Peanuts.”

Schulz died on February 12, 2000, the day before the final strip was published, proving his theory that Charlie Brown would outlive him. That final strip has Snoopy at his typewriter, typing out thanks to those who have spent their time with him.

The cartoonist Art Spiegelman described Peanuts as “Schulz breaking himself up into child-size pieces and letting them go at each other for half a century.” Schulz would have agreed. “Happiness does not create humour,” he once said about his approach to his work. “Sadness creates humour. There’s nothing funny about being happy.”