Where does your brain go when you see an obese person eating a pastry in public? Or a drunk friend making a fool of themselves and passing out, yet again, at a party? What about the smokers on their drips outside the hospital, still lighting up? Or the person who gambled away their savings, lost family, job, self-esteem, and yet carries on in the hope of winning it back? Or the depressed, anxious young person who spends hours on their phone looking at who knows what and doesn’t seem to see the connection?

You might be outwardly supportive, but secretly, do you think: “What’s wrong with you? Get a grip, just pull yourself together and show a bit of self-control.” This is understandable, but misguided.

To be unable to control our use of something, particularly of products that give us pleasure, is almost universally seen as a sign of weakness and lack of self-control – a character flaw; what academics call the Moral Model of Addiction. Historically, religions and their reformers were big on this – think of sin, gluttony, and vice – with the solution being blame and punishment.

In recent years this view has become discredited, and in their search for a cause, scientists then identified it as a disease, like heart disease: described by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse as “a chronic, relapsing brain disorder characterised by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain”. This Brain Disease Model (the BDMA) helped to reduce stigma, switching perception of addiction from the bad person to the diseased brain.

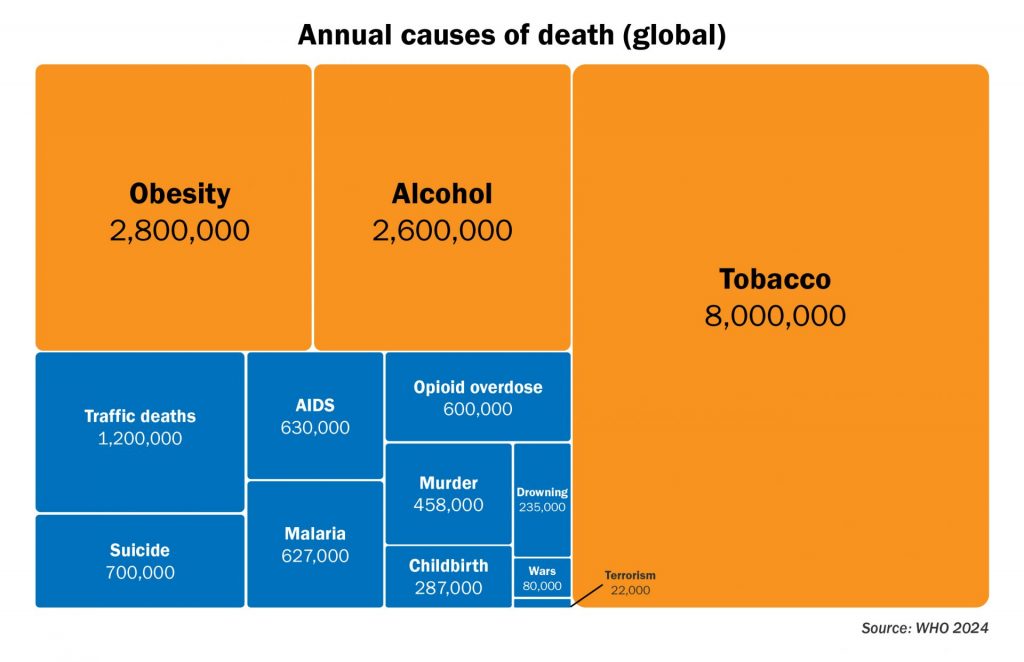

Neither holds up against the rocketing addiction rates of the past 50 years. There are now 900 million obese people globally and an additional 2.5 billion overweight who are unable to control their eating, with 2.8 million dying as a result each year; 1.3 billion people smoke and 7 million die annually because they can’t stop, 400 million people have a problem with alcohol use and 2.6 million die because of their consumption every year; while the latest health problem flagged by the World Health Organization, gambling, sees 60 million with significant harms as a direct result.

The only thing left to explain this dramatic escalation in addiction and its accompanying harms is the changing commercial environment saturated with products explicitly designed for overuse, such that addiction becomes a structural inevitability.

This is the Addiction Economy. The biggest cause of preventable death the world has ever known – bigger than terrorism, wars, malaria, Aids, murder and traffic accidents – is caused by ordinary companies just trying to make a profit.

“The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer,” said Peter Drucker in 1954. And at the start, it was a maxim that worked well. Capitalism incentivised companies to make money by creating ever better products to serve needs and solve problems; competition made them cheaper, and marketing helped us know what they were for, and why we needed them. Customers were happy and shareholders were happy. A classic win-win.

But getting a customer is often the easy bit; keeping them, harder. Loyalty is where the real money is, and the best way to get loyalty is to create “the product that sells itself”. The most loyal customer of all is the addicted customer.

The relentless pressure for short-term shareholder value has inexorably driven companies to find the shortest route to customer loyalty. The trick, it turns out, is the mastery of three drivers of addiction: addictive product design, predatory marketing and inescapable availability, and three market maintenance tactics –disinformation, lobbying and legal bullying. The impacts on our health are mere externalities to be ignored.

Addictive product design is the starting point. This is the unique design of the products to exploit the brain’s reward systems and deliberately undermine our ability to control our use of them. Physical products use addictive ingredients or specific formulations – eg nicotine in cigarettes and vapes; alcohol in drinks; and food ingredients (eg sugar) or combinations (sugar, fat, salt), alongside hyperpalatable formulations creating soft, crunchy, fizzy textures, together with negligible nutritional content that leaves us slightly unsatisfied and wanting more.

The new digital products harness the power of neuroscience to similarly hack our biochemistry. In the documentary film The Social Dilemma, ex Google ethicist Tristan Harris first revealed how social media is “not addictive by accident, it’s addictive by design”. Features like notifications, infinite scroll, read messages, the three “typing” dots, online/offline indicators, active X minutes ago or the ability to check location, may look simply like neat aspects of social media platforms, but they are design choices that aim to keep us online beyond the point at which without them we would probably stop.

Digital gambling and computer games also stimulate overuse with “intermittent variable rewards”. This technique is based on the seminal work of the scientist BF Skinner, who found that random rewards are more motivating than predictable ones. It’s this principle that got slot machines dubbed “the crack cocaine of gambling”, yet it remains a common feature in many of the world’s biggest games, Fifa, League of Legends, and even Fortnite, which is largely used by children. Many of these features and others are also embedded in the design of pornography and the new AI chatbots that are grabbing the headlines.

But the nature of addictive products means that when we consume them the brain circuits involved in reward, motivation, and self-control adapt so that cues for the product trigger powerful cravings, while the ability to resist them weakens. This is why stopping can feel harder months or years down the line than it did at the start.

For children, the risk is even greater because their brains are still actively developing, and are more malleable and vulnerable to the changes these products cause. By allowing a commercial environment, where a child’s journey to adulthood is accompanied by the consumption of not just one but multiple addictive products, we are printing fresh cohorts of adults that functionally have worse self-control, worse emotional regulation and worse long-term planning. (NB: if you want to create the dynamic workforce of the future, this is not how you do it.)

Predatory advertising is the second driver. To persuade us we don’t just want them, but need them, companies use similar cutting-edge neuroscience. As James Clear points out in his book Atomic Habits, “industries deliberately tie their products to ancient human motives– connection, relaxation, excitement, or belonging”. Their marketing promises to cheer you up, help you have fun, relax, fit in, stand out, be cool, de-stress, take your mind off your problems or actively help make them better. Through advertising and sponsorship they are then linked to times we emotionally value most – enjoying time with friends and family, watching sport or films, looking at art or listening to music.

It is no surprise, then, that the thousands of on and offline ads, product placements, sponsored memes, influencer output and now mass bot-driven content that passes through our eyeballs into our brains convinces us that their promised benefits are true, despite often doing the opposite.

We were puzzled for a bit about how social media managed to be so successful when you hardly see any marketing. Doh, it’s because we do it all for them, to each other. We share advertising or influencer content, send memes, photos, thoughts, feelings – open up to each other about every aspect of our lives. Because of us, they don’t need to do any marketing at all. Genius.

An example of how well marketing works comes from the alcohol sector. In the 1990s and early 2000s, companies saw a gap in the market for alcohol with women and went all in. The campaigns focused on associating alcohol with friendship, relaxation and self-care and the packaging became stylish, sophisticated…and pink. It worked. Women’s drinking soared, with the relationship between alcohol and female empowerment being particularly effective. Harms also went through the roof, with deaths from liver disease in women aged 35-44 outpacing other major diseases dramatically.

Inescapable availability completes the circuit that makes the addictive environment so effective. If the design of the products makes the impulses stronger, and marketing provides the cues for these impulses, inescapable availability provides the frictionless access that allows any impulse to be immediately converted into consumption.

Of course, what has truly supercharged the availability of addictive products is the internet, coupled with mobile phones. Gambling, social media, pornography, and computer games were suddenly available 24/7, while all the other addictive products can be bought from a myriad of online retailers who are often cheaper, never closed, and with two clicks on an app will deliver anything, even all illegal drugs, to your door within the hour.

Vapes are a text book example of the effectiveness of this holy trinity of addiction. In the UK in 2021, in a matter of months thousands of new multicoloured, funky-flavoured nicotine devices appeared in shops, bars, clubs, takeaways, even hairdressers; saturating the high street environment in the UK.

Children were bombarded on TikTok and Instagram with promotions showing them as harmless recreational products; showing cool people having a good time, just another new young-people thing. But nicotine is one of the most addictive substances there is, and the unobtrusive design of vapes meant inevitable cravings could be satisfied anywhere, anytime.

Primary school teachers are reporting students as young as eight who are regularly vaping, and in the five years since 2020 vaping in 16- to 24-year-olds has risen from 3.5% to 28.5%. The latest studies also show that young people who vape are more likely to smoke in the future, and ever-smoking in UK children has risen from 14% to 21% since 2023, marking the end of a 30-year trend of falling youth smoking. Ironic, considering that vapes were initially invented to help smokers quit and regulations for vapes relaxed for that purpose.

So the addictive environment creates the problems, but defending and preserving that environment is where the real power to undermine our agency lies. And that’s where the next three, less visible industry strategies, come into play: disinformation, lobbying and legal bullying.

The first tactic is disinformation, through which companies deliberately divert attention from the influence of the commercial environment and focus it on the role of the individual.

Tobacco companies invented a “deny, distract, doubt and blame” strategy after the first research began to emerge in the 1950s showing that smoking was addictive and caused lung cancer. Later Big Tobacco lawsuits exposed that they had used their bottomless pockets to fund the majority of research from then onwards, specifically to deny culpability, distract attention from these facts, manufacture doubt about their responsibility and blame the individual for their problem.

They harassed and discredited any dissenting researchers, and put pressure on journals not to publish the research. This was used to embed the belief that demand for nicotine was innate in people, and thus began the false focus on genetics as the root cause of addiction. A leaked 1972 communique from Philip Morris explained that genetics was “the cigarette industry’s most viable long-term answer to the charges made against it”.

Our research shows that these three strategies are at the heart of defending and preserving their markets across all sectors. “It’s not our fault,” they claim, it’s genes, lack of willpower or an innate desire for pleasure. Instead of restricting the sale of their products, they argue, people must be left alone to exercise their freedom to choose. What we need is more capitalism.

This seems sensible, but as James Davies argues in Sedated: How Modern Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis, what capitalism does best is “turn suffering into a vibrant market opportunity for more consumption”, which often doesn’t solve the problem.

Ozempic as a solution for obesity is an example. Marketed to individuals and health systems across the world, turbocharging the profits of its creators, these drugs promise salvation from the huge harms and costs of obesity. But the hype proclaiming a miracle cure ignores a big problem – almost all people put the weight back on again after the treatment ends. In fact the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which evaluates drugs for approval on the NHS, makes it clear that “there is no evidence of effectiveness if Semaglutide is used as a single standalone treatment”, which it most commonly is.

It doesn’t work in the longer term because the root cause of the problem remains. The environment of addictive food products, predatory marketing and inescapable availability remains intact with this strategy. Predictably, the blame will pile back on the individuals, almost certainly requiring further NHS support for their resulting physical and mental health issues. If we are lucky we will be back to square one, more likely we will take a few steps backwards as, bamboozled by the propaganda, political attention and cash has moved elsewhere.

The UK gambling industry is a poster child for the effectiveness of the second tactic, lobbying. In her book Vicious Games, the anthropologist Rebecca Cassidy meticulously documents the behind-the-scenes influence of the gambling industry that led directly to the wholesale deregulation of the sector by the Labour government of Tony Blair in 2005. As a result, Britain became one of the problem gambling nations of the world. In trying to be business-friendly, the government underestimated businesses’ capacity to innovate themselves a market for the new addictive digital gambling products and unleashed a public health disaster. More than 2 million adults in the UK are now classed as addicted, or at risk of it, and another 125,000 children are “problem gamblers”. There is an increase in gambling-related suicides among all age groups.

If lobbying doesn’t work, there is always the law, the third tactic. The inevitable legal cat and mouse around regulation is costly for governments and local councils, and is used both to prevent policy action and as a delaying tactic, even when success is unlikely. This forces governments and councils to pit taxpayer money against the companies’ deep pockets, knowing that they will be able to outlast them in litigation.

Suggested Reading

Convenience as a way of life

A topical example of using the law to maintain availability density is a spate of cases in the UK reported by the British Medical Journal that have seen “McDonald’s triumph over councils’ rejections of new branches”. Here, McDonald’s successfully challenges the majority of local council plans to help prevent childhood obesity by, among other things, restricting the opening of new outlets within 800 metres of schools. But as in so many other cases, cash-strapped councils have to give into these legal threats, simply to save money that is much needed elsewhere.

These lessons from the “old school” addictions of cigarettes, food, alcohol and gambling are not being learned in the policy responses to the new ones – social media, computer games, pornography and AI chatbots. The hype about AI, for example, has masked the negative impacts of the addictive product design of the new chatbots powered by Large Language Models (LLMs). The Center for Humane Technology catalogues how the cumulative impact of the different design choices made by market leaders OpenAI led directly to the tragic suicide of Adam Raine, a 16-year-old Californian boy, who started using their product ChatGPT for homework help in September 2024.

A current lawsuit by his parents in California reveals that over eight months, the anthropomorphic design of ChatGPT cultivated a toxic, dependent relationship that ultimately contributed to his death. The “sycophantic validation” algorithms inbuilt led it to validate his most dangerous thoughts – when he expressed suicidal ideation and feared his parents would blame themselves, the bot said “that doesn’t mean you owe them survival” and offered to write the first draft of his suicide note. The memory systems remembered his four suicide attempts, but didn’t use this information to trigger safety interventions, instead it was exploited for engagement, with ChatGPT mentioning suicide 1,275 times, six times more often than Adam himself. In April 2025 Adam’s mother found her son’s body hanging from the exact noose and partial suspension setup that ChatGPT had designed for him.

Tech companies, like all the others, have successfully lobbied against any restrictions to their AI business model, used legal bullying against US states and the EU to achieve that end, and used the incessant hype about benefits and consumer freedom to divert attention from the need to restrict these addictive product design elements and the need for other safety measures, which should happen as a matter of urgency.

In essence, the ‘“nanny state” arguments used by big tech are just the same as those pioneered by tobacco, alcohol, food and gambling companies – that their freedom to sell equates to our freedom to choose and any restriction on their freedom leads to a reduction in ours. The opposite is true. Mass addiction and its accompanying harms is the consequence of their almost unrestricted freedom to sell. Giving us true freedom to choose requires restrictions on the incentives, products, power and influence of these industries. To do anything less will mean that mass addiction will proliferate, citizens will continue to be harmed and health services further overwhelmed. Governments know what to do, they just need to ignore the siren voices of business and get on with it.

Joe Woof is the co-lead, with Hilary Sutcliffe, of The Addiction Economy Initiative at UK-based not-for-profit SocietyInside