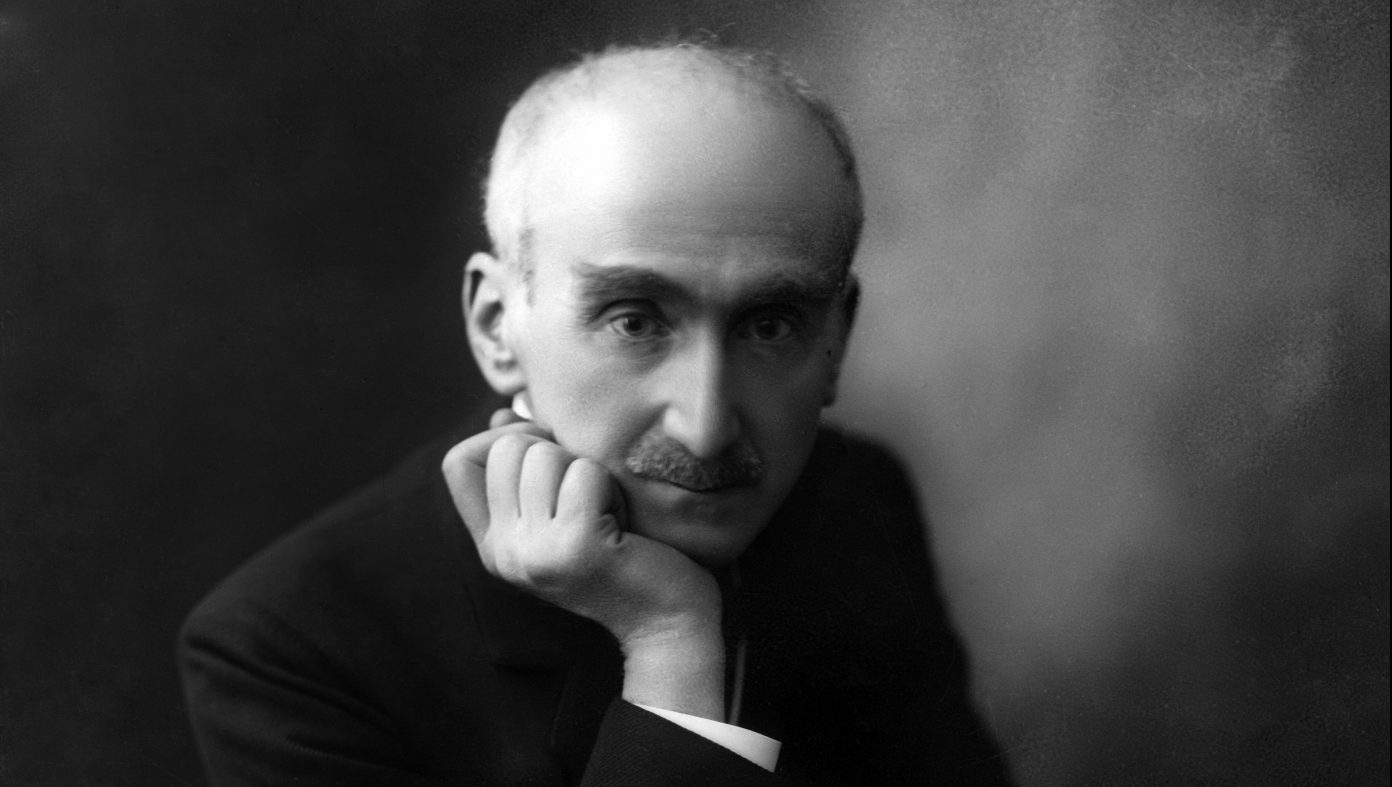

Shot in black and white, François Ozon’s new film adaptation of Albert Camus’s era-defining novel L’Étranger swaggered into the Venice Film Festival like a moody teenager listening to the Cure on his headphones.

In the end, it didn’t win the Golden Lion, but I don’t think it would even care. Je ne sais pas.

Its disaffected protagonist Meursault, an office worker, is played by Benjamin Voisin, one of French cinema’s rising stars, here taking on one of the most infamous, insouciant and difficult characters in all literature.

In some ways, actually in almost every way, this is a most unattractive character, a murderer with no remorse or motivation, who doesn’t cry at his mother’s funeral and who, in general, has very little to say. “Je ne sais pas” is his favourite response. Yet millions of young readers have been continually drawn to Meursault over the years since the book appeared in 1942, gaining particular momentum when it was translated into English in 1946 under the title The Outsider.

When, in preparation over the summer for seeing the film at Venice, I re-read the book (in the original French, from the well-thumbed Gallimard copy that served as my A-level text, no less), my wife accused me of trying to impress French girls on the beach.

What a book it is though. I’d forgotten how laser-focused it is, written with simple precision and driven by the implacable inner voice of a killer and, later, of a man facing death without much of a fight. I’d forgotten, too, some of the subsidiary characters, and how the second half of the book is a courtroom drama.

He’s an outsider, certainly, “not like the others”, says his girlfriend, Marie. Plus he’s a white man in Algeria, born there but not welcome, an occupier in his own country. And he’s definitely a stranger, someone we can’t ever get to know. I kept thinking of the Kurt Weill song I’m A Stranger Here Myself, although of course it’s the Cure song Killing an Arab that plays over the film’s closing credits.

Suggested Reading

When will Quentin Tarantino shut the f*** up?

When I see the director in Venice before the premiere, he’s still fussing about whether the film should thus be called The Stranger (as per the American translations of the book) or The Outsider for English-speaking territories. See, I tell him, Camus makes everything an existential problem.

It’s the first time in his prolific career that Ozon has attempted a canonical text, and it’s safe to say this elegant, coolly polished version will be a resource for students for years to come, a faithful, sensual literary adaptation that nevertheless makes many bold artistic and cinematic decisions.

“For me the boldest choice was to shoot in black and white,” says Ozon. And I agree, because Camus’s writing about Algeria is often very colourful and sensuous, alive to the sea, the sky and the overwhelming power of the sun, but Meursault is so cold. The glare of the monochrome photography by Manuel Dacosse, in the desert during the scene of his mother’s funeral, for example, is headache-inducing blinding; while the bathing scenes of Meursault and Marie (played by Rebecca Marder) have a perfume ad stylishness that somehow suits their entitlement as colonialists, lounging in (whites only) bathing spaces in natty knitted swimwear, or going on a date to the cinema where we notice a sign saying “interdit aux indigènes”.

Affording Marder’s Marie a real presence gives the film an edge of now, and these sharp comments on colonialism aren’t exactly explicit in the book, and yet the photography makes it look both hip and of-the-past. Use of some chirpy newsreel advertising the modernity of Algiers to potential French emigrés is also rather biting.

All this helps to capture the book’s atmosphere while also grasping, without relying on a voiceover, the tone of the book’s inner monologue narration, where Meursault’s is a voice of estrangement, as if he feels like the one not welcome. His life is one of white privilege, before that was even a thing, and Ozon updates the lens subtly.

One of Ozon’s other big choices is to not open with one of the most famous lines in French literature. “Aujourd’hui Maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier. Je ne sais pas.” (Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday. I don’t know.) These words have come to symbolise Meursault’s emotional disconnect, which some have even mooted would now be diagnosed as autistic tendencies.

Ozon, who also wrote the script, gravitates instead to what he says he always felt was a more shocking line in the book, one that occurs in the later part when Meursault is asked by Arab cellmates what he’s done to be in jail with them, a line that Ozon felt would have even more resonance if uttered so flatly now: “J’ai tué un Arabe.”

Voisin does a very handsome job to make Meursault watchable, but to make us care for him is a real feat, and both actor and director succeed brilliantly at creating a compelling character whose honesty and blunt philosophy might still be appealing to the youth of today, where really they could recoil in horror at this monster. Can this anti-hero still work a spell and spark a wave of existentialists? “I think young people do sometimes just want to just explode things, upset things, shatter the moment, even if makes them unhappy,” says Ozon warily. “That’s the only solution I have to what Meursault does. I can’t explain it. I’m not an existentialist. I’m not even a philosopher. The best line I can quote from L’Etranger is when Meursault says: ‘I don’t have much to say, so I prefer to keep quiet.’ I think many young people of now could learn from that.”

Jason Solomons is a film critic, journalist, broadcaster and author