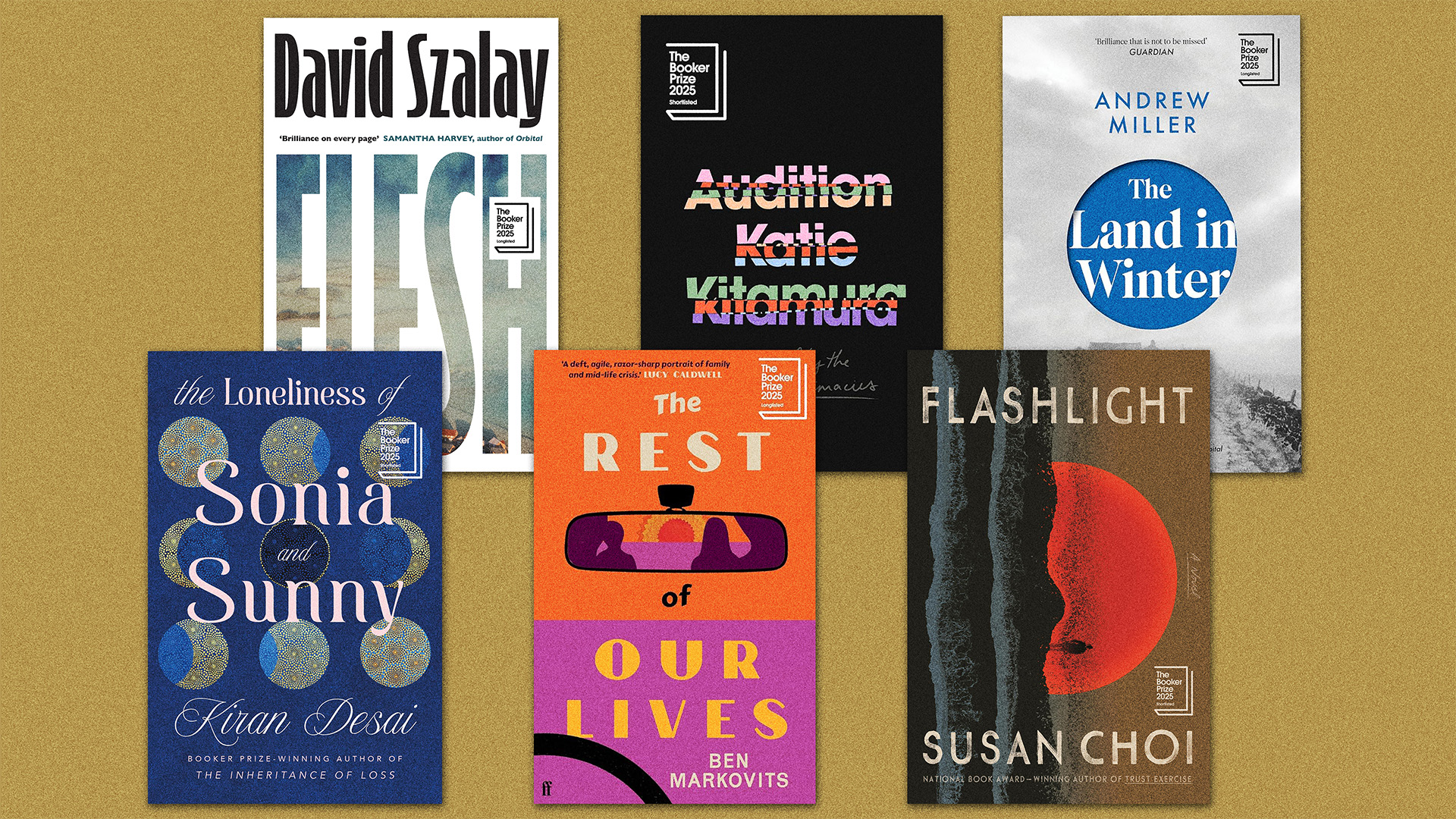

The Booker Prize shortlist reveal is now a public event. On September 23 , at the Royal Festival Hall, the final six were unveiled by the judging panel – Nigerian novelist Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀, actor, producer and publisher Sarah Jessica Parker, writer, broadcaster and literary critic Chris Power and Booker Prize-longlisted author Kiley Reid – with Roddy Doyle as its chair. It’s the first time a Booker winner has been in that role, Doyle having won in 1993 for Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha.

I would have loved to be a fly on the wall for the decision-making process. In my mind, I envision Carrie Bradshaw starring in Twelve Angry Men-esque scenes, the judges sequestered in airless rooms for weeks until consensus emerges.

Often with these announcements, you can see an overarching theme linking the selections. This year, the thread between all of these books seems to be the impact of parents on their offspring. Does that influence, even when rejected, determine the outcome of the child’s life, as in Kirai Desai’s The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny and for Michael in Ben Markovits’s The Rest of Our Lives?

Does a tragic childhood event, and crucially the parental reaction to it, define the trajectory for the rest of that child’s ensuing life, like in David Szalay’s Flesh and Susan Choi’s Flashlight? Or does the manner in which a child is brought into the world dictate how it will eventually react to that parent, as is projected in Andrew Miller’s The Land of Winter and Katie Kitamura’s Audition?

For me, this year’s shortlist is as varied as it is surprising. If I were in the room, I couldn’t say it would’ve been the same.

Flashlight, by Susan Choi

Flashlight originated as a short story in The New Yorker, and Choi later planned it as a novella. Yet as a reader who was captivated and curious at the level of detail and the exploration of schooling, adaptation and masking that Choi covers, I can’t imagine the novel being any shorter than the 464 pages the judges read. It starts with Louisa, a ten-year-old girl whose Korean father drowns while they are on a beach, while their small family is on secondment in Japan. The anger, brilliance and craftsmanship of her words have stayed with me for months.

Suggested Reading

The Rest of Our Lives lacks a punchline and a point

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, by Kiran Desai

At the other end of the spectrum, this doorstopper of a novel clocks in at 700 pages and was 20 years in the making. Desai won the Booker in 2006 with The Inheritance of Loss and would be the fifth double winner in the 56 years of the prize’s history. Sonia and Sunny’s story is one of rejecting their respective families’ previous attempts to matchmake them, only to run into one another on a train in a chance meeting. What could easily be a meet-cute in any number of genres takes the invisible thread theory to another level in the novel, set from the mid-90s to early 2000s. The immigrant experience of seeking a home and understanding is explored beautifully in this epic tale.

Audition, by Katie Kitamura

This short book, comprising two competing narratives, was my surprise favourite of the long list. Audition introduces us to an actress and a man just young enough to be in a relationship with her. I loved the exploration of how children begin to see their parents as humans with fully realised lives and existences outside of them, and how the flipside of that affects the child’s maturing relationships, romantic and with those same parents. I did not expect this to make the shortlist, but I love that it did. It’s no surprise that it’s been optioned by Higher Ground Productions, Michelle Obama’s production company, as a feature film, to star Lucy Liu.

Flesh, by David Szalay

For a book about the hungers of flesh and the dangers of existence, the main character István, is mostly a passive man. There is very little that he instigates, yet his reactions to almost everything are minuscule but have massive implications. The book begins curiously as we are faced with a teenage István being seduced by a questionable and manipulative female neighbour, with lasting ramifications. I was drawn into the detached telling, but ultimately perplexed by a novel that had more plot points in the last 200 words than in the previous 200 pages. Flesh had a promising opening that didn’t end up delivering for me.

The Land in Winter, by Andrew Miller

This exploration of two couples stranded in proximity in an uncharacteristically bleak and record-breaking cold winter of Bristol in 1961-62 made me think of the neighbours we found ourselves “bubbled up” with during the first lockdown. Two pregnant couples from drastically different backgrounds, each in crisis and exploring bleak surroundings. Fear and seemingly never-ending circumstances lead to fascinating character exploration in The Land in Winter, but it consumes too much of the plot. This feels like it should be the most classically Bookerish of the novels on the shortlist. And yet, I found myself dipping in and out without much urgency to return to it.

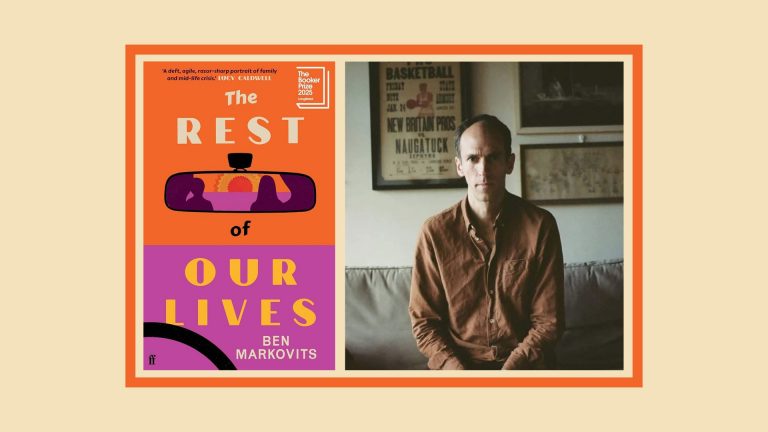

The Rest of Our Lives, by Ben Markovits

Previously for The New World, I have detailed the myriad reasons that this story of a man’s road trip across America after dropping his daughter off at university didn’t reach its destination for me. I’m shocked it was even published, let alone lauded enough to make its way to the shortlist. I am convinced this would not have been the case if the same book had been submitted for publication with a female writer’s name attached.