One of my favourite experiences is when a book surprises me, charms me and contradicts my initial dismissive impression. Recently, I have been confounded and delighted by In Defence of the Act by Effie Black, Pod by Lailene Paul and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders, books I never expected to enjoy. It took me until halfway through to change my mind about Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason; soon I was completely won over.

I finish every fiction book I start. I believe the authors deserve my attention for the entirety of the story they are telling and don’t think I am entitled to critique a book I have not finished.

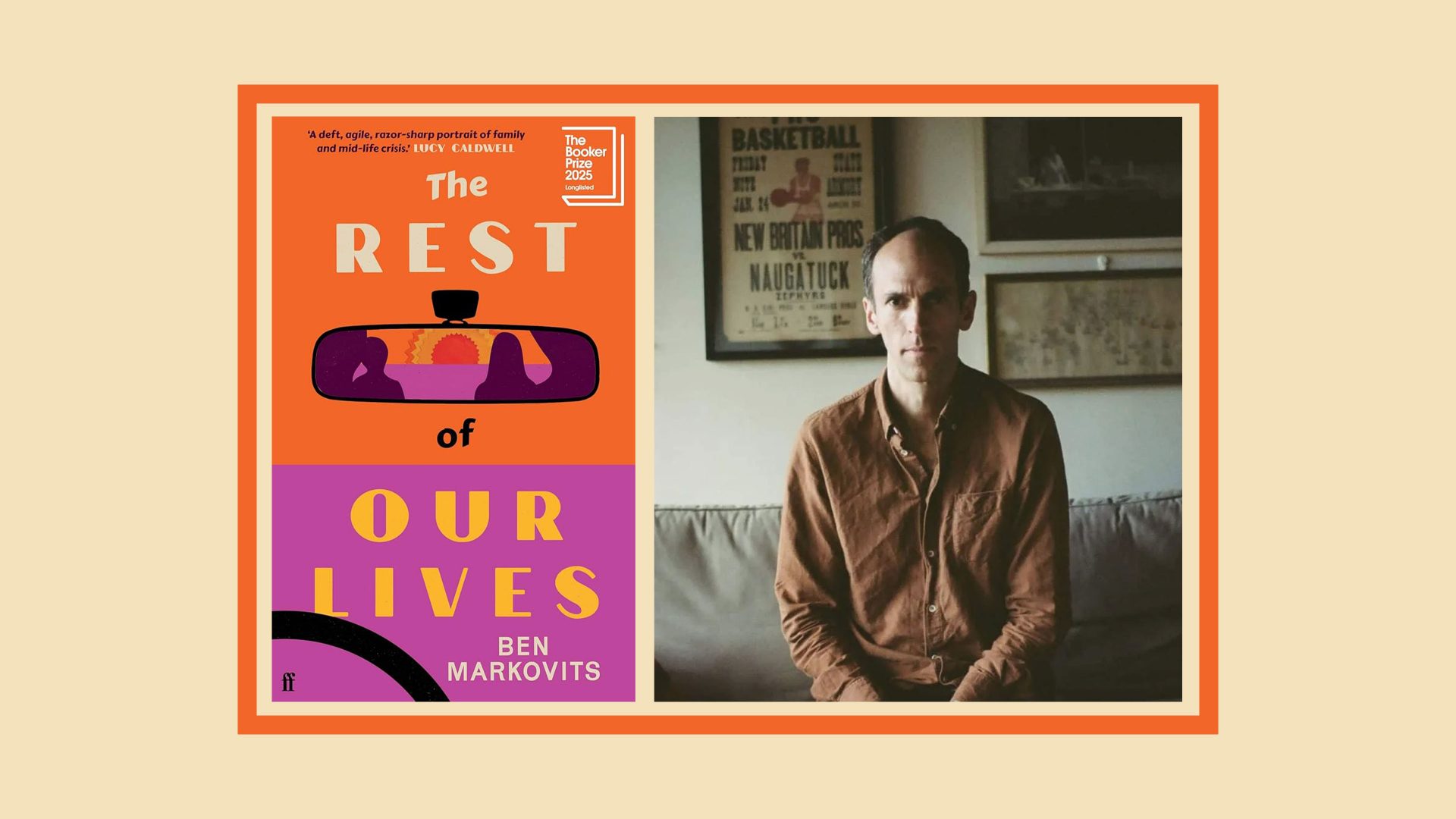

So I finished The Rest of Our Lives, the Booker-longlisted novel by Benjamin Markovits, and I loathed it.

First impressions were not good: I resented the pink and orange cover, masquerading as elevated chick lit. The book jacket description made me think of the hundreds of books about midlife crises and awakenings that go uncommissioned because they are written by women about women rather than men and men.

I hoped to have those first impressions challenged and that I would finish curious about what else Markowits had written, with new insight into the perspective of the recently divorced men in the dating pool that I am unhappily and masochistically swimming in. Instead, I got a beleaguered account of a breadwinning husband whose wife was unfaithful 12 years earlier. As he heads off on a road trip, we’re supposed to sympathise with him for soldiering on while his wife parents their children and he goes to work as a law professor at the top of the pay scale. Forget him being complicit in a fractured relationship that resulted in his partner’s infidelity, he’s one of the good guys because he stayed, he was at the dinner table and stayed in his kids’ lives and didn’t trade his wife in when she committed adultery.

Tom has a “C-minus marriage, which makes it pretty hard to score much higher than a B overall on the rest of your life.” His character is one of those people who believes that every life choice, every bit of agency is based on whether your parents provided you with an upper-middle-class home and stayed married. As if miserable parents who despise one another can provide a healthy start in life.

Suggested Reading

Universality, satire that’s highly in tents

I was baffled by the emperor’s new clothes of this book. After dropping off his daughter at college in Pittsburgh, Tom drives across the country to California in search of himself, but his character development arc is nonexistent. There is no come-to-Jesus moment for a tedious man with no self-awareness or actual intention for growth, but with the need for validation that he is one of the good guys.

Tom’s mild misogyny and racist tendencies are excused as generational, while his having functional relationships with his children, a healthy bank balance and interest in another perfunctory and performative marriage make him a rare catch.

An old girlfriend briefly holds the reins of caretaking a fully adult man until his son’s girlfriend takes over from her to literally keep him alive. She then hands the responsibility for him back to his adulterous wife, who no doubt will live out her days paying penance for wanting more and having the audacity to seek it 12 years ago.

I would have much rather read the Big Little Lies-esque psychological dark thriller his obliquely sketched first girlfriend could have written about finding an ex she had had no contact with in 20 years showing up unannounced and sleeping in his car in her driveway at an address she had not shared with him or given permission for him to have.

Or did I miss the punchline? Was The Rest of Our Lives meant to be a completely satirical take on the burden of men being infantilised and a skewering of modern marriage, and I missed it?

The same story told from his wife’s point of view would not be lauded and longlisted. It would not even be published.

Jamie Klingler is the co-founder of London Book Club