There is nothing more disappointing than starting a novel and immediately feeling like you are not the intended audience. I cosily settle myself in with my phone silenced and the dog happily snoozing next to me, only to read a jarring clanger of a character description. Suddenly, the author has broken my trust and willingness to be wooed by them. Unfortunately, Jonathan Buckley’s Booker-longlisted One Boat did just that.

One Boat is a performative, yet shallow dive. Upon losing her father, Teresa returns to a tiny village in Greece where she last spent a week when her mother died nine years ago. It’s a coastal town rather than a holiday spot, a location no one actually visits for more than two nights. Yet somehow, her extended stay almost a decade ago managed to make an impression on both the residents and the grieving guest.

As readers, we are given access to Teresa’s rambling journals and her reflections on her own notes from both trips. Both are tiresome and meandering. Teresa’s interactions with a few locals and another tourist are meant to be profound and telling, but read as condescending and verbose.

Our first introduction to the female protagonist makes it glaringly obvious that she is being written by a male author. Buckley writes: “A single female diner, looking around, might be misconstrued as someone in need of company, so I took out a notebook and a pen to raise a modest barrier. It signified Do Not Disturb clearly enough, I would have thought, but it did not work.’ Clearly, Buckley is unaware of the lengths women have to go to be left alone.

A guest in the hotel spends several days and meals telling his tragic backstory to Teresa. If I were in that position, I would have moved hotels the next morning (if not left the country…). Does Buckley believe that women have nothing better to do than act as a passive entity for men to be heard? Throughout these pages, Teresa’s main purpose is to be the audience for any man who deems her worth speaking to. She’s the vehicle for the story without having been developed as a sentient creature herself.

Making your main character a vessel to make the male characters more rounded and nuanced feels like a cheat. Last time she was on this Greek island, she was reading The Odyssey and this visit, it is The Iliad, but it is only later we find out that her choice of books is only because they are the local mechanic’s favourites.

Basically, she is the perfect ChatGPT girlfriend. We not only need to read her disjointed, italicised, incredibly superficial observations, but we are also somehow subjected to her notes about taking notes, all of which are centred around whether or not men are validating her and noticing her.

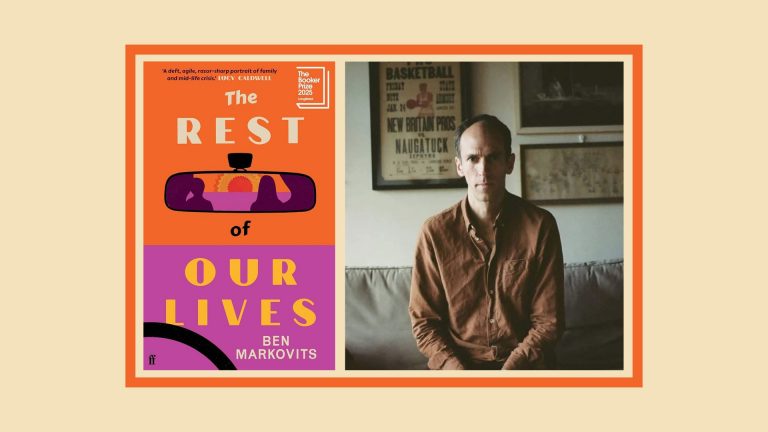

Suggested Reading

The Rest of Our Lives lacks a punchline and a point

This is best evidenced by Teresa’s reflections from a conversation with Niko, the diving instructor. “Quantum physics hasn’t changed the way most people think about the world. It’s incomprehensible to 99% of us, but that’s besides the point, I told him. A new window is opened in the palace of knowledge – that’s what I said. I noted it later, with: ‘I lectured him- embarrassing.’”

When travelling alone, there is definitely an element of people watching and imagining what people’s backstories are, but not through the lens of a third party. I understand arriving somewhere you’ve been before and looking around for familiar faces, but her entire experience is about how people are noticing or not noticing her. Even on a solo holiday, Teresa has no main character energy; she is subjected to a stranger’s tragic story, the telling of which spans multiple days and meals.

The intention and impetus to leave a husband to go to a tiny Greek village surely allows you to escape the responsibility of humouring a random guest at the same hotel. Given the detail of mundane experiences she is recording, you’d think there would be some indication of her contribution to the conversation other than being a receptacle for his stories of woe.

The other local woman, Xanthe, describes another woman as “a sexy body, very woman.” I like to be complimentary to women, and have often complimented their presence, how they command a room or their beauty, but this is such a basic and reductive male description.

When we are reading about Teresa re-reading her own observations, we are left with this doozy of a sentence. “Which begs the question: who’s scrutinising the scrutiniser? And where do we find the scrutiniser of the scrutiniser of the scrutiniser?” It refers to her discussion with the Iliad– and Odyssey-loving mechanic Petros, who was as bored with Teresa as I was.

Sometimes I get the impression that certain books are not interested in my readership, that I am not smart or well-read enough to appreciate Literature with a capital L.

One Boat never feels like it wanted me as a reader. Every bit of plot or conversation is overexplored, overstated and exhausting. Ultimately, by the time the protagonist has had anything to say, I’d lost the will to listen.