Britain has a long love affair with spying – most of us are raised first on the flashy antics of James Bond and then the more cerebral Cold War thrills of John Le Carré. We’re a nation long past the peak of our power, but spying is one thing that we still do well. Or so we like to think.

The collapse of the criminal case against two men accused of spying on MPs for China has threatened that image of competence, and the government and opposition are engaged in a furious battle of finger pointing over who is to blame.

Christopher Cash, the former director of parliament’s China Research Group, was accused of passing sensitive information to Christopher Berry, who in turn was accused of knowingly acting as an agent of the Chinese state, passing Cash’s information to a government official in exchange for payment. Both men were arrested and then charged under the Official Secrets Act, but the prosecution was abandoned over the summer. Both men have denied all wrongdoing.

On Wednesday night, the government released three witness statements from the deputy national security advisor Matthew Collins in connection with the case. These statements quickly shatter any illusions that this was some high-level operation of the type seen in fiction.

The information passed from Cash to Berry was little more than low-level Westminster gossip – claims that Tom Tugendhat would soon get a job in the cabinet (he didn’t), or that Jeremy Hunt would withdraw from the Conservative leadership contest and endorse Tugendhat (he didn’t, he endorsed the eventual winner Rishi Sunak instead). China would have been better informed by simply reading UK newspapers than from anything they were passed by Cash or Berry.

Similarly, the men look clueless even when seeming to incriminate themselves. At one point Cash allegedly told Berry “you’re in spy territory now”. When passing on his ultimately worthless titbits of information he reportedly said the information was “very off the record” and not to be passed on to “your new employer”, sometimes also referred to as his “Zhejiang interlocutor”.

Regardless of the apparent low value of the intelligence referred to in Collins’s witness statement, MPs were understandably furious when they learned of the operation and of the arrests. Tugendhat had become security minister in the intervening period, and was now adjacent to cabinet. The Crown Prosecution Service was dealing with an acutely political case, and one in which understandably furious public figures were determined to see action.

The problem came in the detail of the Official Secrets Act, the offence under which Cash and Berry were ultimately charged. The Act targeted any person who “obtains, collects, records, or publishes, or communicates to any other person any secret official code word, or pass word, or any sketch, plan, model, article, or note, or other document or information which is calculated to be or might be or is intended to be directly or indirectly useful to an enemy”.

The critical word in this sentence is right at the end – “enemy”. The UK has a complex relationship with China. It is a major trading partner that buys British financial services, pays our consultants handsomely and sends us cheap manufactured goods. It is also a competitor: a “threat” when it comes to spying on our government and businesses.

But as a matter of deliberate policy, the last Conservative government did not classify China as an enemy, and neither has the current Labour administration. Instead, Britain operates a framework of “cooperate, compete and challenge” – cooperating where it’s in our interests, competing in other areas, and challenging “where we have to”. China is regarded as an intelligence threat, but not as an enemy state.

Collins, who is deputy national security advisor, submitted two additional witness statements trying to play up China’s role as an intelligence threat, while clarifying government policy both today and also when Cash and Berry were active. He did so in an apparent attempt to help the CPS prosecution, but evidently this was not felt sufficient to enable a prosecution under the Official Secrets Act.

There is an additional problem here for the Conservatives – the requirement for information to be passed to an “enemy” had been flagged up as a weakness of the Act since at least 2015, but the government had not addressed this in 2022, when the alleged offences occurred.

The definition of espionage was finally updated in the National Security Act of 2023, which creates an offence of “assisting a foreign intelligence service” and defines this by saying “a person commits an offence if the person… engages in conduct that is likely to materially assist a foreign intelligence service in carrying out UK-related activities”, and either knew or ought to know they were doing so. The new laws don’t even require prosecutors to identify a particular foreign intelligence service.

Suggested Reading

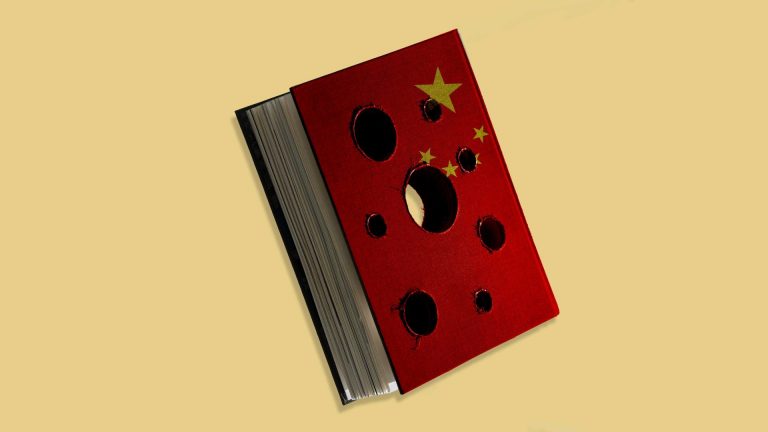

China’s new dark history

It is not difficult to see why prosecution under the 2023 Act might be a lot easier than under the previous legal regime. But laws are not retroactive, and so the updated laws were no use in this case.

This creates a problem, because the British political and administrative system is fundamentally incapable of admitting any mistakes. The Crown Prosecution Service’s somewhat bizarre line is that they were correct in their actions to charge Cash and Berry under the Official Secrets Act, and correct to drop those prosecutions this summer.

It is not hard to see why, perhaps, a charge might have happened that shouldn’t – when the security minister was personally targeted by the alleged spying activity, alongside other MPs, the CPS would worry about looking weak and ineffective by not bringing charges, and might optimistically have hoped for a way around the laws.

The Labour government then inherited a case that was extremely likely to lose. Prosecutors were pressuring officials for a statement that would help them to reach the threshold of “enemy” in court, not just as a matter of current policy, but retroactively applying it to the government of 2022. It is not hard to see why this was an impossible problem. The government is not supposed to intervene in criminal prosecutions, and yet it was being asked by prosecutors to do just that. There was no win here.

At the same time, the Conservative front bench is faced with the simple fact: if it had reformed the Official Secrets Act quicker, instead of waiting for eight years and one major spy scandal to do so, this case might not have collapsed. Kemi Badenoch is constitutionally incapable of admitting fault – it’s questionable whether she can even see it – so she and her shadow front bench are acting as attack dogs on a story which makes them look at least as bad as the government.

The result is a classic Westminster farce, in which once again it looks as if the British state can do absolutely nothing right. The alleged spying activity by the two men looks clownish, and yet the top echelons of the British state can’t do anything about it.

Worse still, if this was an attempt to avoid diplomatic embarrassment with China, it has backfired entirely. The government has yet to decide whether to let China build its new mega-embassy. This spying row has made that decision all the more sensitive – and it is one that will matter far more to Chinese officials than this Westminster scandal. The deadline for this has now been delayed until December.

“What is forgotten about this ongoing spy saga is that the Chinese government, like any country, would price in their ‘alleged’ intelligence assets being compromised, caught, and prosecuted,” explained Sam Goodman, senior policy director of the China Strategic Risks Institute.

“Ironically, by attempting to spare the blushes of the Chinese, it now makes it harder for the government to support China’s new embassy, as it would be used by their opponents as evidence of them being too close to China.”

The diplomatic fallout of the row will depend on the government’s choices about the embassy. The wider fallout might be political, though, as this row plays into a toxic pattern of behaviour between the Labour government and Conservative official opposition.

The British state screws something up, and the Tories try to blame Labour. Labour, in turn, throws it back at the last Conservative government – and the two drag one another into the mud. Meanwhile, an unscathed Nigel Farage and Reform can point to it as an example that both parties, and the whole Whitehall machine, have failed totally, and a radical change is needed.

Unless both major parties find a way to break that pattern, their everyday activity is doing little more than paving the way for Farage to enter Number 10. If they’re going to work so hard to get him elected, surely they might as well just defect?