The turkey is cooked, cooled, and the leftovers have long since gone bad. The firework displays are done. Grudgingly, we are left to accept that the Christmas and new year’s holidays are all but over – they’ve taken 2025 with them, and it’s now time to look ahead to see what 2026 might bring.

In these turbulent political times, what follows is less a set of predictions as to what might happen in UK politics throughout 2026, and more a guide to the coming year – what’s in the diary, what it might mean, what to track and how to interpret it. Will the year ahead be as grim as the one just gone? Let’s find out.

THE MAY ELECTIONS

Bizarrely, we can already be almost certain of the headline we can expect in the aftermath of widespread elections across the UK in May – which are already being called “midterms”.

That story will be Wales: it is all but guaranteed that Labour will come third in elections to the Senedd, a cataclysmic outcome for Labour in a country where it has topped the ballot in every election for the last 100 years.

There is a much more open question as to who will come first: Plaid Cymru and Reform are virtually neck-and-neck in the contest, with the Welsh nationalists currently slightly favoured to take the most seats. Oddly, though, the winner of this contest is unlikely to prove pivotal: whether they come first or second, Plaid Cymru governing in some form of coalition with Labour as the junior partner is the likeliest outcome.

As Labour’s first loss in the Scottish Parliament to the SNP showed, once it loses a stronghold, it never easily wins it back. Losing Wales will be seismic, both for the party’s electoral prospects and its very sense of identity. The fact it will be a distant third will only make it hit harder. Wales rarely dominates the UK’s political conversation, but this is likely to be the rare exception.

The election news is unlikely to be better for Labour elsewhere: it is expecting dismal results in Scotland, which is significant but has happened before. The real nerves will be over Labour’s last remaining heartland of London, where local officials anticipate truly dismal results. At that point, expect panic.

Reform is, of course, expected to be the main beneficiary of the elections, but expect significant pickup for the Green Party too. The Conservatives are likely to have an awful night, but can perhaps rest easy that it will be overshadowed by the government’s dreadful results.

THE AFTERMATH

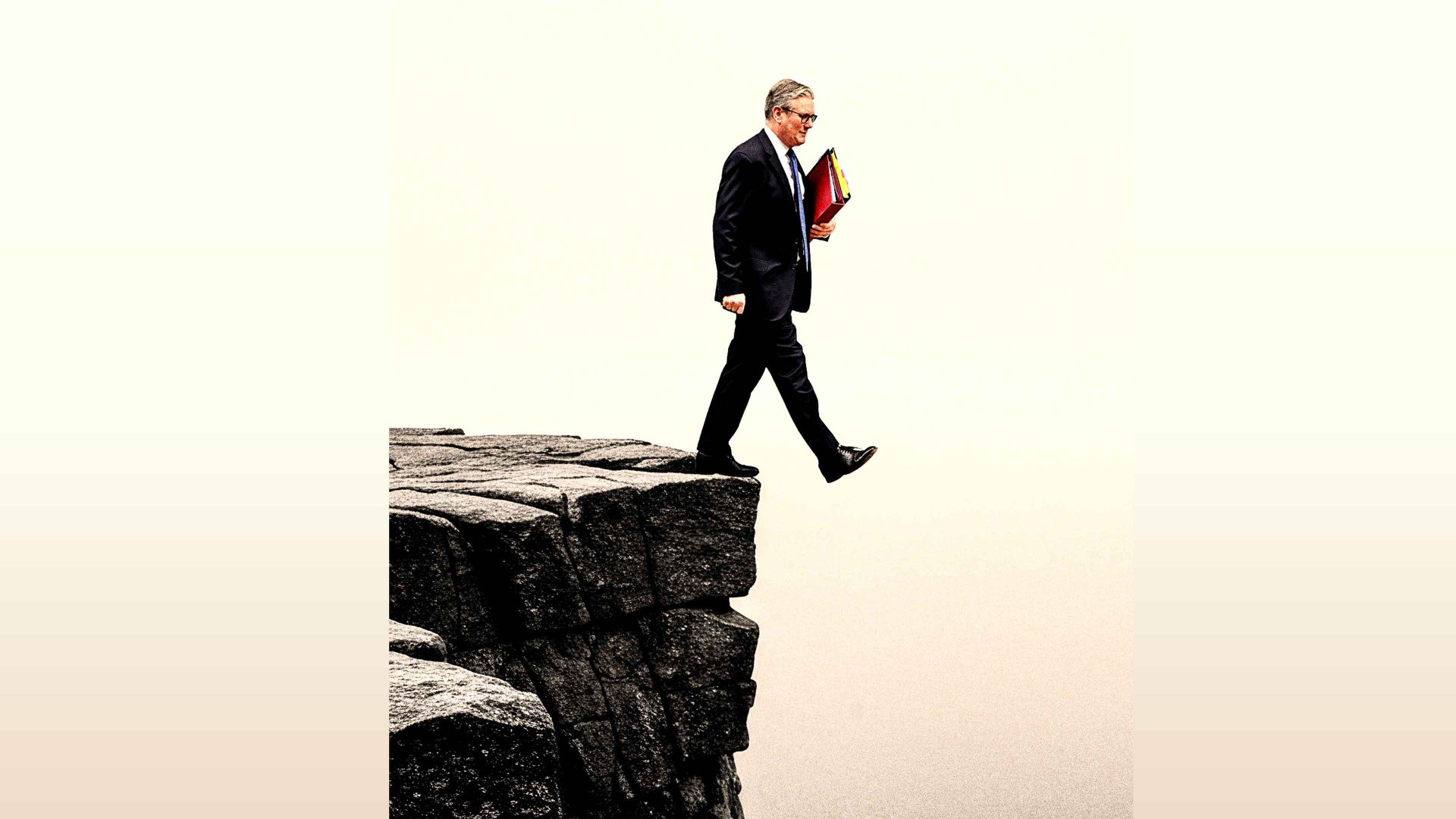

Labour MPs are barely trying to hide the fact that they are planning to overthrow Keir Starmer. People elected as loyalists – and who fully expected to actually be loyalists – are among the keenest to make sure Starmer’s premiership doesn’t last through 2026. Counter-intuitively, the May elections have helped keep him in place so far. MPs believe the results will be terrible and that this is now unavoidable. As a result, they did not want to install a new leader only for them to be immediately tarred with huge electoral losses. They also calculate that the results will make a challenge easier.

All of that means that a leadership fight after May is inevitable. Conservatives have been successful – perhaps too successful – at ousting their leaders when bad news happens, but Labour’s record is much patchier. This time, plotters are determined to make it happen.

The harder problem is the matter of a successor: almost all of the major contenders have vulnerabilities. Angela Rayner is dogged by scandal. Andy Burnham isn’t an MP. Ed Miliband has already been leader. Neither Wes Streeting nor Shabana Mahmood is well-liked by party members. Because the race is wide open, expect sniping between potential contenders to kick off long before a contest is declared.

Despite a current insistence that Kemi Badenoch is suddenly “performing better” in Westminster – largely driven by the lobby getting bored of the running narratives – the Conservative leader looks similarly doomed, with the party polling at record lows even against a wildly unpopular government. If she is ousted, expect Robert Jenrick to take the mantle without much of a contest.

Suggested Reading

Is 2026 the year that Britain’s universities go bankrupt?

REFORM’S NEXT ACT

Even their most ardent critic would have to acknowledge that Reform in 2025 had the kind of year of which most politicians can only dream – almost everything went their way. They are leading the polls and leading the conversation, having managed to turn not just the Tories but increasingly Labour, too, into imitations of themselves, watered down to differing degrees.

Some of that good news and momentum will continue, at least for a time. A great performance at the May elections seems all but guaranteed, as does a steady stream of further defections – perhaps including the first Labour MP to jump ship to Reform.

But what goes up must come down, as Farage himself privately seems aware, having told more than one supporter in passing to “enjoy it while it lasts”. Farage has twice before built political parties that managed to poll at 30%, have huge success in local or European elections, and then collapse before a general election happens.

Might this happen a third time? It’s not impossible. Reform is finding governing local councils just as difficult as everyone else. Farage is good at building movements, but not at sustaining them. The party doesn’t look like a government in waiting, and while filling its benches with Tory defectors handles that problem to an extent, it also risks the party looking like the Conservatives in a slightly differently coloured rosette.

Moreover, Farage is always bad on the back foot, quickly showing himself as thin-skinned and defensive – witness his reaction to the Russian funding scandal, the ongoing questions about his own historical racism, and his party’s confused approach to free speech, which includes banning The New World from its events. Farage might be in the ascendancy, but his path to No 10 is still strewn with hazards.

LOOKING TO EUROPE

In electoral terms, 2026 will be a relatively quiet one for most of Europe. While there are widespread fears that either or both of France and Germany could fall to the far right, neither has its major election next year, and Europe-wide elections are years off. Europe’s far right, emboldened by the US’s security strategy openly declaring its support for them, will have to bide their time.

That leaves Europe to prepare, and to respond – and to decide whether it wants to get serious about its new security situation, and its new relationship with the US. So far, it has proven able to occasionally issue strongly worded statements, but has accomplished little else.

A key challenge early in the year will be whether, having already raised a multibillion-euro loan for Kyiv, European nations can convince Belgium to unblock plans to release further tens of billions in frozen Russian assets to fund Ukraine’s war effort. There is also the question of whether it can meaningfully invest in its own defence industries more broadly.

For the UK, the question is whether talk about resetting the European relationship can move beyond an occasional soundbite trotted out by Keir Starmer and Yvette Cooper, to become a meaningful strategy. There was good news in the last days of 2025 when the UK re-entered the Erasmus exchange programme, but this was always on the table and available to the UK since Brexit itself.

The UK’s failure to fully participate in the EU’s €150bn defence investment scheme was a dismal one, especially when even Canada – notably quite far from Europe – managed it. EU nations are keen to work out closer cooperation with the UK, though wary of signing deals a Reform government could then scupper, but are increasingly sceptical of the UK’s willingness to meaningfully engage.

LEGISLATION TO WATCH

Looking to policy, the prospect of a change of leadership partway through the year means much is up in the air, but there are a few significant bills to particularly watch that will probably matter whoever is in charge.

One, very much tied to European security concerns, is the endlessly delayed publication of the UK’s Defence Investment Plan. Starmer’s No 10 operation is trying to position the PM as relentlessly focused on major issues of diplomacy and international security – but the UK’s defence plan has been delayed twice, and is now not expected until next year, reportedly over concerns about “affordability”, risking this becoming another issue on which the government says much then does very little.

Politically, in the early months of the year, the most significant bill might be one the government is determined to argue (somewhat dishonestly) has nothing to do with it: assisted dying. Peers so far have rejected calls to rubber-stamp the bill, and have tabled more than 1,000 possible amendments for consideration. The bill, for which support does not split neatly across party lines, could make for significant political headaches whatever happens with it.

Perhaps the most significant legislation lies in bills that give Labour an opportunity to consider what powers it should leave to whichever government comes next. Labour has long promised Lords reform, and is still trying to abolish hereditary peers – but Starmer has already packed the Lords with more Labour MPs than abolishing hereditary peers will remove.

Nothing at present would stop prime minister Farage doing an even more audacious act of packing the Lords with Reform legislators for life. Might Labour give up some short-term advantage to change that?

A final significant bill on that front is the Elections and Democracy bill, which is expected early in 2026 and is now at least somewhat delayed pending the result of a review into foreign interference in UK politics, sparked in the wake of Reform’s Nathan Gill scandal.

Whatever Labour does here will be pilloried as partisan and antidemocratic, so it might as well take a big swing – tightening up rules on laundering foreign donations, tackling crypto donations, setting spending limits across a whole parliamentary term and not just campaign periods, and generally making the laws fit for the 21st century.

Surely the bad headlines would be worth it to safeguard future elections – and might give Starmer something of a legacy, should his premiership prove to be shorter than he might hope.