On Friday, a rag-tag group gathered from across the country at Birmingham’s NEC to meet up, socialise, and to discuss what the future might look like. Young, alternative, and dressed up for the occasion, these were early arrivals for “VeXpo 2025” – a convention for fans of Japanese anime. This year, they had to navigate their way through a very different crowd – for, they were sharing their conference space with Reform UK.

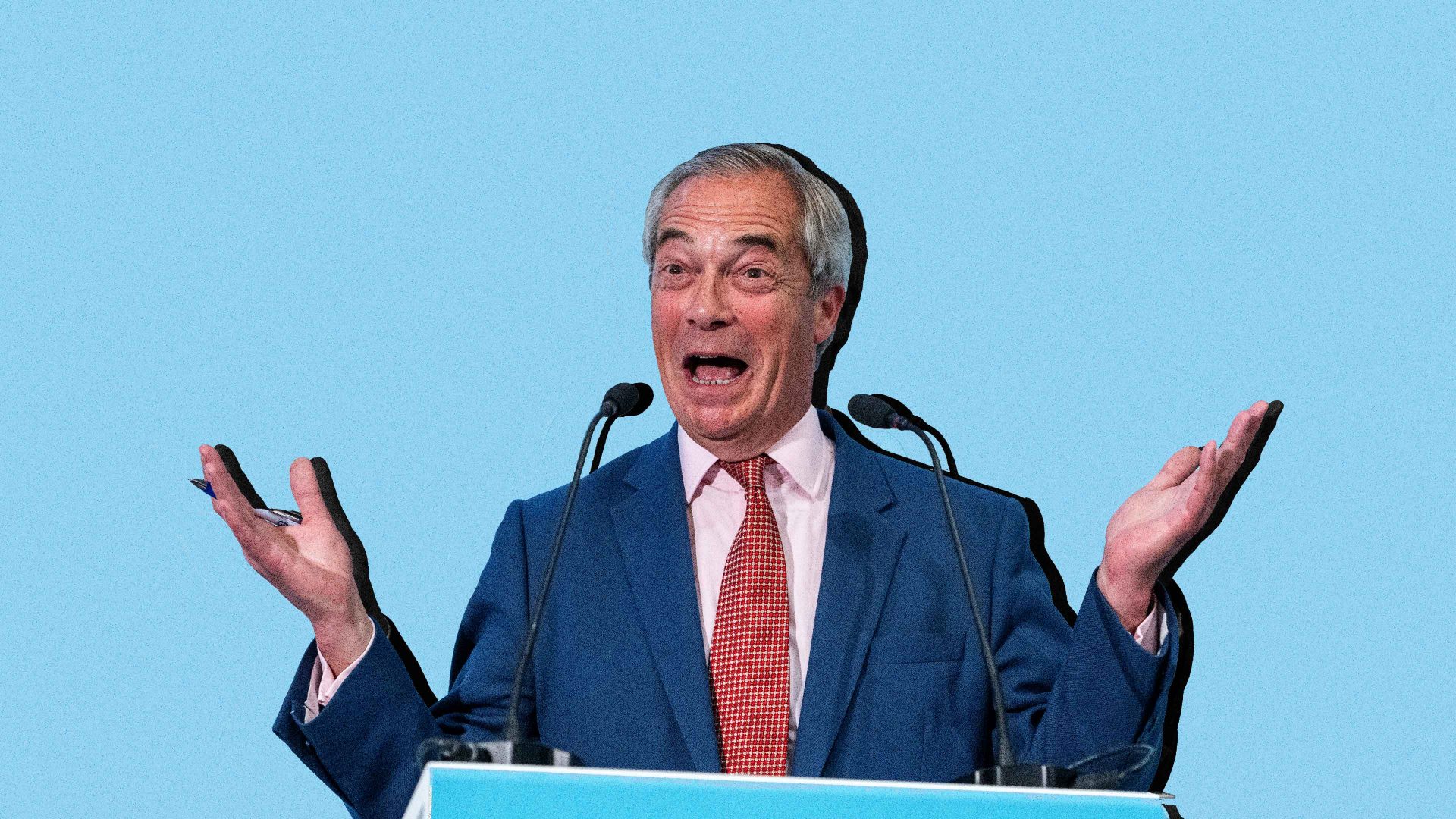

Event security had little difficulty in working out who was meant to be directed in which direction. Almost anyone under 40 was there for the anime, while Reform’s crowd tended toward Nigel Farage’s male, pale and stale demographic, with fifty shades of tweed and even more variations of teal.

The men wore teal ties, light-blue suits, and several had already purchased “FARAGE 10” football shirts for the event, which could be signed by Farage himself for an additional £100 a time. The women sported teal jumpsuits or dresses, with one group even wearing custom-made “Nigel’s Angels” t-shirts.

Reform’s big talking point for their conference was the plant to overthrow the government by 2027, not 2029 as previously advertised. Labour were in such chaos, Farage intended to argue, that an early election was becoming increasingly likely. Reform could change the government even sooner than anyone had imagined.

Unfortunately for Farage and Reform, even as his enthusiastic supporters queued to get into the conference, it became apparent that Keir Starmer was going to change the government even more rapidly than Reform could ever manage. Angela Rayner had resigned before Reform’s first speaker took to the main stage. As party chairman David Bull tried to warm up the crowd, the political journalists in the crowd started to get an indication that something monumental was going on elsewhere.

The New World had an unusually good vantage point for all of this, thanks to the Reform party. Just 48 hours before the conference, as Farage addressed the US Congress on freedom of speech, Reform banned this publication from its conference: an email explained that our accreditation had been revoked. That meant that our conference HQ was set up in the NEC’s Wetherspoons, which was conveniently right next to one of the main thoroughfares between the conference hall and the train station.

Suggested Reading

Chicken Farage bans The New World

And as Bull spoke, he assured the crowd that, “We do welcome an independent and free political press,” a remark that, sitting there in the Wetherspoons, I thought rang a little hollow. Hoping to test his commitment, I checked my DMs to Reform’s deputy leader Richard Tice, who’d I’d messaged to see if he’d sort my credential as a “gesture of goodwill” to show his “support for free speech”. Sadly, in lieu of a response was a message from X: “you can no longer send Direct Messages to this person.” Hmm.

Despite this setback, TNW’s Reform conference media room (the ‘Spoons) proved a good stopping-off point for speakers and journalists allowed in the hall, many of whom gladly shared material from inside. It was also an excellent vantage point to see those who were leaving early. These included a senior editor from a national paper who dashed back to London less than half an hour into the conference – “there’s no fucking point being here today, is there?” – and the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg and her producer, who had an intense discussion about how long they could stay.

A large part of Reform’s purpose at their conference was to show they were professionalising – that they were becoming a party of government, and not just of protest. Everything was in place to do that. Unlike last year, the event had a real programme of fringe events held by major think tanks and chaired by policy wonks. That’s what a party does when it’s getting serious about policy. Major corporate sponsors had bothered to turn up, for the first time. The slickly-produced production was being livestreamed to around 5,000 people on YouTube – whose comments descended into an argument over whether Reform or the far-right Advance party were the best hope for Britain, and whether or not YouTube was censoring the England flag. In hosting terms, Reform had its act together.

And yet none of it was going to matter, and a visibly frustrated Nigel Farage could tell – which was why his keynote conference speech was delivered three hours earlier than scheduled. Farage, never a great details man, showed the strain as he tried to look, on the one hand, delighted by Angela Rayner’s departure and on the other, furious at its cause.

“You simply can’t get away with being the housing secretary and avoiding £40,000 in council tax,” he told the conference. But the outgoing deputy PM had underpaid stamp duty, not council tax. Farage may have struggled to get indignant on stamp duty, having taken legal steps not to pay it himself only last year.

Farage had promised to buy a home in his Clacton constituency when he ran for election there last year. In practice, his partner bought a home there, because Farage already owned a property. This is entirely legal, and voters might decide it more-or-less fulfils his promise, but it did serve to reduce the stamp duty owed on the transaction. Rayner had acted similarly, by declaring her new Hove home to be her primary residence. Given Farage was battling another tax story from the Guardian, over his GB News earnings, the Rayner issue was not straightforward.

Perhaps for that reason, Farage was quick to move on to a new message: this conference was proving that Reform is a real political movement that’s much bigger than him. “Is this a one-man band?” he asked the audience, who dutifully shouted back “no”.

This might have been more convincing if the same audience, just ten minutes earlier, hadn’t been asked by Andrea Jenkyns – who walked on stage singing a self-penned song “I’m an insomniac” – to stand up and “please repeat after me that Nigel will be prime minister”, to which they had similarly dutifully obliged.

All modern political parties are presidential, but Reform’s biggest advertiser on its exhibition floor, Direct Bullion, had huge photos of Nigel Farage personally endorsing their products. All of the Reform-themed football shirts on display at the conference merch stall had only one name on the back: “Farage”. When Reform promises “a party that speaks with one voice”, it’s very clearly his.

Suggested Reading

Did Farage just lie to US congress under oath?

After all, Reform got elected with just five MPs in July 2024, and two of those are no longer with the party. James McMurdock, who has a conviction for domestic violence (which Reform says it knew of when he was a candidate), is suspended over questions about his company’s Covid loans. Rupert Lowe, who helped bankroll Reform, has launched his own rival political party after a fallout with Farage. Even Zia Yusuf, now Reform’s head of DOGE and head of policy, quit as chair amid a row over Islamophobia. It has not been smooth sailing.

Still, Farage has found new friends – one of whom, former Conservative cabinet minister Nadine Dorries, took the stage in the middle of Farage’s speech. “I’m delighted we’re going to have the experience, the talent, the hard work and the loyalty of Nadine Dorries,” Farage said, introducing the person who wrote two vicious tell-all books eviscerating the Conservative party.

“Loyalty in a political party is everything, whether it’s from its members or from its MPs or from its councillors,” a shameless Dorries told attendees. “I know what it’s like to be disloyal, I’ve learnt, I’ve been around 30 years, I’ve learned the error of my ways. Moving forward, what is important is saving our country, and the only way we can do that is with a party that is united behind its leader.”

If Dorries looked confused on loyalty, Farage soon looked confused on policy. Just minutes after he had welcomed Dorries into his party, the former Tory secretary of state responsible for the Online Safety Act, he promised to “police the streets and not the tweets and change all that damaging legislation”.

That confusion went further, with Reform’s conference audience clearly often unaware who they were supposed to cheer and who they were supposed to boo. They were, apparently, supposed to cheer on non-doms and cutting taxes for them, and be angry about VAT on school fees – but they didn’t seem to have got the memo.

The crowd didn’t seem too sure about Farage’s promise of “serious cuts to the welfare budget”, either. And when it came to health, consistently a top three issue for the voting public, Reform’s conference could only offer up “vaccine skeptic” Aseem Malhotra, who threatens to become Britain’s RFK Jr in the event of a Reform victory.

Nigel Farage has spent most of his political career being a right-wing libertarian with views regarded as fringe by most of the British public. He now finds himself at the forefront of a political party whose voters are a long way to the left of him economically, and who are generally more authoritarian than him, too. In time he may have to reckon with that, but the conference was predictably united around one issue: immigration.

Farage has spent his entire political career stopping short of calling for mass deportations – his schism with Rupert Lowe just six months ago was over that very issue. But that era is very much over, and when speakers hammered the issue of immigration, their audience was behind them, no matter how extreme they got.

“We know the United Kingdom is being invaded,” Reform’s newly-minted head of policy Zia Yusuf told the crowd, making ever more elaborate promises as to the tough treatment refugees would get. The borders will be closed. There will be a five-year programme to “track down, detain and deport” migrants.

Some analogies seemed poorly thought through. Yusuf promised “the most audacious deportation flights since World War 2,” which is not a period most of us would invoke when discussing the forced movement of people. He promised Reform would set up a team to service and repair planes full-time, so deportation flights could run around the clock. His audience lapped it up. There would “not be a judge in the country who would be able to prevent a single deportation”, Yusuf pledged – a promise which would all but overturn the rule of law in the UK. This was what the crowd had come to hear. They loved it.

His closing elevated a new star to the firmament of British greats. “We are the land of Nelson and Churchill, of Shakespeare and Rowling.”

But between Angela Rayner’s resignation and the Labour reshuffle, Reform’s conference didn’t make a single front page. It barely made a ripple in the political press, either: Friday’s “Playbook PM” political newsletter didn’t mention Farage’s speech until paragraph 23. But in reality, neither Nigel Farage nor his devotees in the hall had much reason to care.

As pundits, academics and professors stopped by The New World’s field headquarters, almost all of them mentioned the same thing and said it had stopped them in their tracks. The polling group More in Common had presented new research on what they’ve called “The Reform UK iceberg”.

The study found that 12% of those polled said they had voted for Reform UK last year – but 30% would vote Reform now if there was a general election tomorrow. Beyond that, 42% would at least consider voting for Reform, and a broader still 49% would either consider it, or had a positive view of Nigel Farage.

Reform and Farage are getting more extreme than they have ever been. The party has little coherence, no policy outside immigration – where Donald Trump-like policy promises have been scattered liberally – and Farage has no more ability to keep his party onside than ever before.

But this time, none of it seems to matter. Farage has a serious base that is already willing to vote for him, and a larger group that’s happy to consider him, which is enough to build the kind of electoral coalition that could sweep him into power. Reform might not be serious, but they need to be taken seriously – and they know it.One senior analyst dropped in at TNW’s Wetherspoons table. “It may be the end of democracy,” he said, as he left, “but it’s nice, at least, being at a conference where everyone looks happy.”