When a whistleblower whose dossier brought down the head of the BBC – one of the world’s most powerful media organisations – gives evidence to a committee of parliament, it feels like it should be the stuff of high drama: of raised voices, shocking revelations, and gasps.

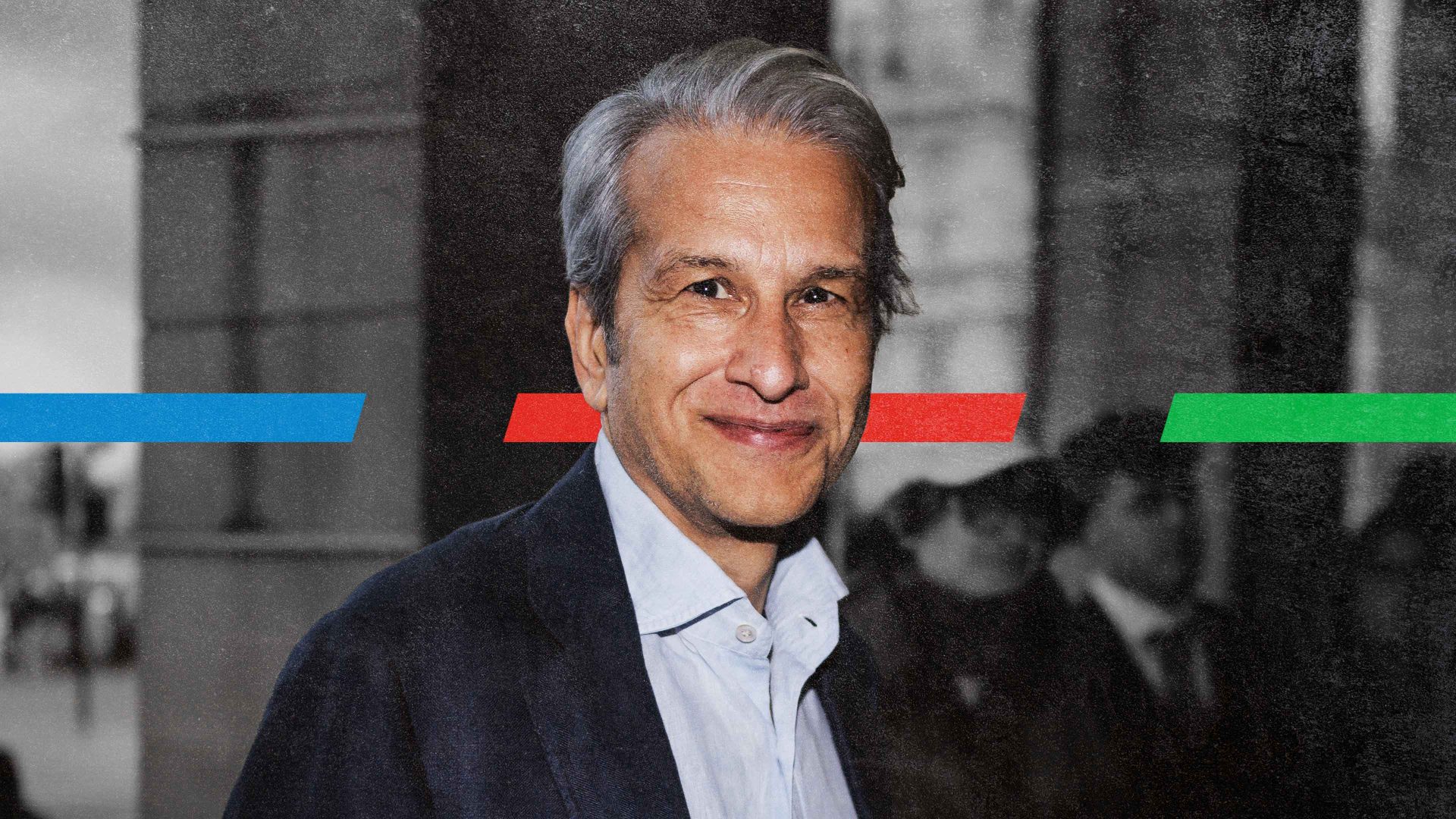

The reality of Michael Prescott’s evidence session before parliament’s Culture, Media and Sport committee was significantly more mundane. Prescott endured a grilling so light it could barely be called a defrosting, and yet he still seemed confused and largely out of his depth throughout.

When it came to the core facts of his motivation, Prescott made a disappointing poster child for enemies of the BBC. He described himself as a “centrist dad”, repeatedly and said he didn’t think the BBC was “institutionally biased”. When pressed on whether he thought Panorama had unfairly damaged the reputation of Donald Trump in the way the programme had edited a speech made by the president – a crucial bar that Trump’s billion-dollar lawsuit against the BBC must clear – he answered “probably not”, with a grin.

Prescott seemed genuinely a little confused and upset by the furore that his dossier had caused, saying he hoped the issues it raised would be quietly resolved behind closed doors. He took “no pleasure” from the resignation of Tim Davie, he said, describing the outgoing director general as a “supreme talent” and adding “it’s a tragedy he’s gone”.

If Prescott was an assassin, he’s certainly a sorrowful one. Several of his responses on the details of his dossier were baffling. Prescott’s dossier raised the example of the “History Reclaimed” group, whose concerns he said were insufficiently considered by the BBC.

When asked during the evidence session whether he was aware of their political campaign and goals, he admitted he hadn’t even Googled the group before including them in his report.

Prescott also repeated, several times, his expectation that the Panorama episode on Donald Trump and January 6th would be followed by an “equally” aggressive episode on Kamala Harris – but was not pressed on what, exactly, this documentary would be expected to reveal. Trump, after all, led an insurrection. Should the BBC have pretended that Kamala Harris had done the same? Answer came there none.

Part of this was the absolutely woeful standard of the questioning from MPs. Notably, during a 90-minute long evidence session, Prescott was at no point asked to explain why his own dossier traduced a Trump quote at least as seriously as the Panorama episode to which he referred.

But this was just one missing question among many. Prescott was not pressed to give a timetable as to who had the dossier when, who knew he was preparing it, if anyone knew he was distributing it more widely – to DCMS and Ofcom – a few days before it was leaked to the Telegraph, or other basic facts.

Where MPs landed on a question that might be interesting, they soon rambled off the topic. Prescott revealed he considered controversial BBC board member Robbie Gibb to be “a friend”, but declined to share details of his correspondence with Gibb with the committee, saying (wrongly) it would be “quite a precedent” if he did. Witnesses routinely share evidence with parliamentary committees in these contexts.

Worse was to come after Prescott, when three BBC board members took his place at the witness desk – chairman Samir Shah, senior independent director Caroline Thomson, and Gibb.

To the obvious frustration of MPs, Shah responded to even basic questions with five or ten minutes of waffle, sometimes losing his own thread to the extent that he had to ask the MP to repeat their question.

In amongst this verbal barricade, Shah revealed he wanted to get to the bottom of why the BBC’s responses during crises were so slow and inadequate, declaring himself to be mystified as to why this was the case – even as his third or fourth meandering return to the topic made the reason clear to anyone else paying attention.

All three directors declared themselves outraged and appalled by accusations that the leak of Prescott’s dossier could have been part of an orchestrated plot involving board members against the BBC’s management. To even suggest that, all three said, was an outrageous attack on people of the outstanding calibre of the BBC board.

Thomson took this further, saying she was truly baffled by the very idea of an orchestrated plot involving the board, because its formal meetings involved so much discussion and disagreement. This suggests either Thomson is woefully incompetent – the suggestion was not that the board had collectively agreed to plot, but instead that some of its members had exploited the crisis through backchannels – or that she is willing to look incompetent in public in order to avoid a not-very-tough question.

Reports of the BBC’s worst week suggest both Deborah Turness, CEO of BBC News, and Tim Davie were so frustrated by the board’s response to the unfolding crisis that it fed into their decisions to quit. Having watched just 90 minutes of three of its most senior members speaking to parliament, it was not hard to see why someone would quit their dream job rather than sit through more meetings with this lot.

If Shah and the BBC’s board had hoped their appearance would give the impression the BBC was in safe hands and that the worst was over, the result was anything but. Just hours later, on Tuesday morning, the organisation was plunged into a fresh crisis as Reith lecturer Rutger Bremen said his criticism of Donald Trump in this year’s lecture had been “censored” by the BBC, at the “highest levels”. Shah will doubtless once again be left to wonder why the board is at least a day late and a dollar short.

Shah is the most senior figure at the BBC not to lose his job over the Prescott dossier farce. Those who watched Monday’s evidence hearing might begin to wonder. To lose one top boss looks like misfortune. Two looks like carelessness. But might three be a blessing?