The departure of Morgan McSweeney – announced in a rush-out Sunday afternoon press statement – is not the first time Keir Starmer has lost a chief of staff during his premiership.

That dubious honour belongs to former civil servant Sue Gray, who resigned after just three months in No 10 after months of bitter media briefing, widely believed to have been orchestrated by McSweeney himself.

This isn’t even the first time McSweeney has departed as Keir Starmer’s chief of staff. He was shifted aside into another role – the party at the time was determined to try and hide that this was a demotion – in 2021, when Starmer’s time as leader of the opposition seemed to be going badly, and his popularity was at what was then a low.

No 10 could, then, try to frame McSweeney’s departure as just another staffing change. But everyone knows the reality is different. McSweeney’s exit leaves Starmer himself hanging on by a thread, with no obvious way back.

Suggested Reading

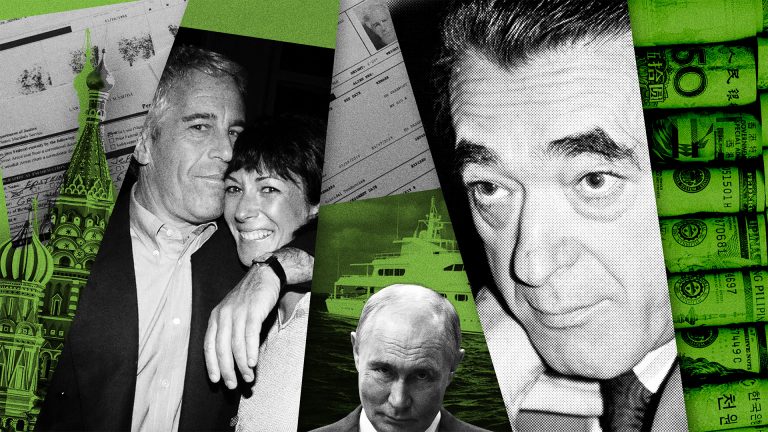

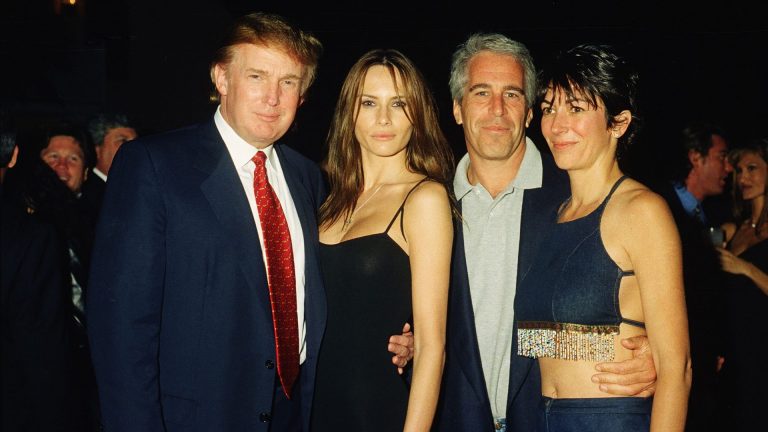

The Mandelson-Epstein crisis proves Labour’s next leader must be a woman

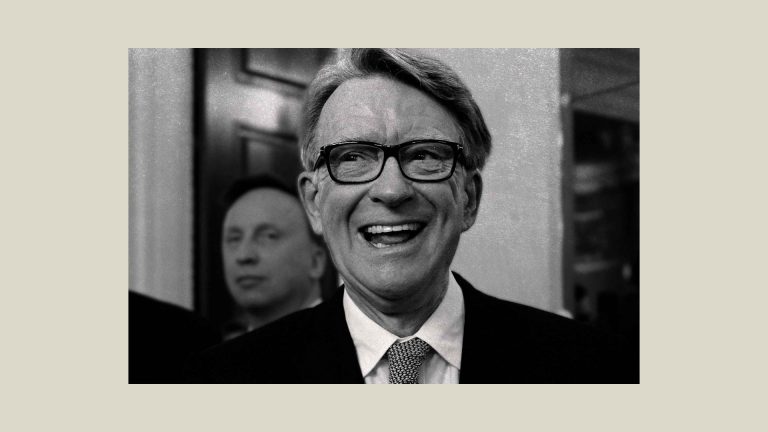

McSweeney’s departure is ostensibly about his role in the decision to appoint Peter Mandelson, his onetime mentor, as US ambassador. That appointment – widely seen as coming about because Mandelson was agitating for a big job in return for his help to the Starmer operation during the Corbyn leadership and opposition – has clearly proven to be a disaster.

But it was not McSweeney who made the final decision on that appointment. His resignation statement makes this very clear. “I advised the prime minister to make that appointment,” he writes, “and I take full responsibility for that advice”.

That leaves a very obvious question: why is the advice to appoint Mandelson a resignation matter, but not the actual decision itself?

McSweeney has left his boss and former colleagues to answer that question, as well as to face the inevitable terrible headlines as documents relating to the decision are published over the coming weeks.

Perhaps Starmer might have hoped his aide would hang around until those documents were published, so that his resignation would take the heat out of the story then. For whatever reason, that hasn’t panned out – some say McSweeney knew how this would end and didn’t feel the need to hang around for it.

Others suggest that No 10 felt a departure now was necessary. A third possibility is simply that McSweeney was not willing to further sully his own reputation to support the prime minister’s.

Given they are the shared architects of a political project, Starmer and McSweeney have never seemed personally close – Labour aides particularly speak in astonishment as to how McSweeney’s camp described their boss in the book Get Out, as little more than the man sitting at the front of an automated Docklands Light Railway train, pretending he’s driving. Perhaps McSweeney was simply no longer willing to put his neck out.

Suggested Reading

This is the end for Keir Starmer

Whatever the cause, Keir Starmer is now undeniably isolated. His rise to the premiership was always a lonely one. There is no grouping of MPs that represent his longtime friends and allies, no wider Starmerite ideological grouping upon which he can draw. Almost all of the staff who accompanied his rise to power have already gone.

To put it bluntly, politicians need people they can throw under the bus when necessary. Starmer has no one left to throw, and no shortage of traffic barrelling directly towards him.

He has weeks, if not months, of further disclosures around the Mandelson scandal to come, especially since No 10 has yet to even agree procedures for disclosure with the Intelligence and Security Committee. He has the result of the Gorton and Denton by-election – one of Labour’s heartland seats – to survive. He has Scottish, Welsh, and local elections coming up in May that are expected to be a disaster. And he has no one else left to blame.

Very little about Morgan McSweeney’s exit came as a shock or a surprise. It was seen in Westminster as inevitable. The problem for Keir Starmer is that his exit in the not-too-distant future feels a lot like an inevitability, too.