The default mode of Westminster coverage is to speak of everything in terms of politics. Whatever the issue, whichever legislation is under discussion, it is spoken of in terms of what it means for the government, for its polling, or which minister is up or down.

This stuff does matter, because government matters – but it means that the actual impacts of policies rarely make it to the front pages, and are often skipped entirely. When that happens, the human stakes of the issue at hand are lost, sometimes with devastating effect.

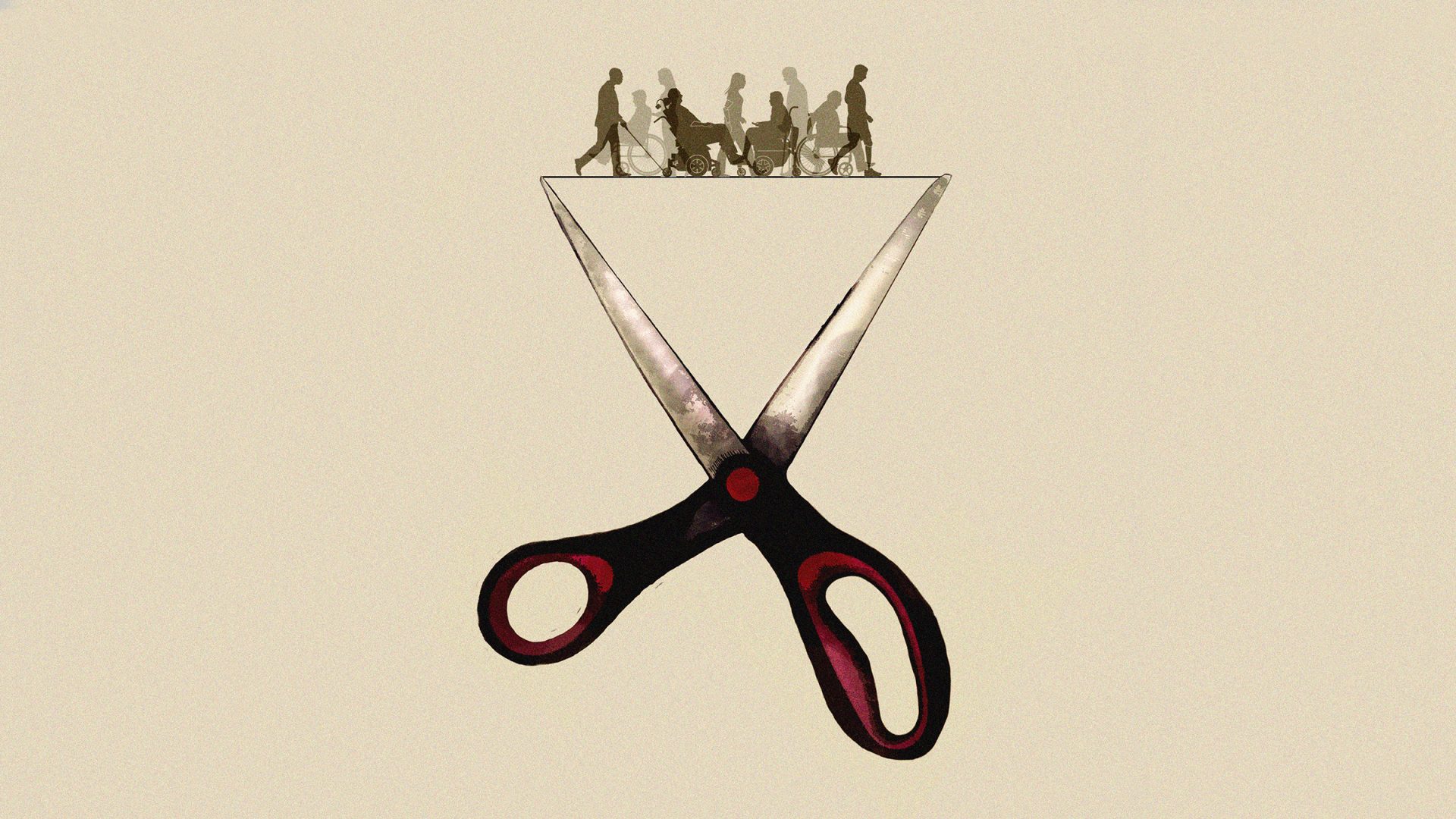

There is perhaps nowhere this is more obvious than with the government’s reforms to disability benefits, which were tabled in the Commons on Wednesday. These were initially presented as a means to save £5 billion during the Spring Statement, at a time when chancellor Rachel Reeves desperately needed to find money to show she would still meet her fiscal targets.

The government is now trying to reframe the new policies as part of much-needed reform to the benefit system, which it argues is spiralling in cost while also failing the people it is supposed to serve. But the rushed rollout amid an obvious need to find cuts has got the policy off to a terrible start.

The government now faces the fury of disability campaigners and its own backbenches alike. On Thursday night, Labour MP Vicky Foxcroft resigned as a whip, citing that cuts to personal independence payments and universal credit should “not be part of the solution”. But all of this is just the politics of the situation.

Suggested Reading

The flawed Assisted Dying bill still deserves to succeed

In the real world, the government’s reforms could be a devastating blow to some disabled households, from which they would have no means to recover. It proposes to change the rules on Personal Independence Payment (PIPs) from an existing system which grants the payment to people who score above a certain threshold across a range of questions, to also requiring people to score a certain number of points in at least one area.

This might sound like a small but technical change. But in practice, this means that people with serious conditions with relatively small but meaningful impacts on a wide range of activities – such as earlier stages of Parkinson’s or Multiple Sclerosis – might lose their payments. For some, that would also mean that their partner would lose their eligibility for carer’s allowance. Losing both payments at once would mean a loss of over £10,000 overnight.

People with disabilities are among the most likely to be living in poverty already. Losing £10,000 of their income overnight would straightforwardly be devastating to many such people, and it is not as if their health suddenly changes when the government’s benefit criteria do. This is why campaigners have been ringing and meeting MPs so frantically in recent months.

For a time, it seemed like the government might have learned something from its recent mooted u-turns. After almost a year of sticking to its guns on winter fuel allowance – from which no-one lost more than £300 – the government largely reversed its policy. It is expected to scrap the two-child benefit cap this autumn.

Labour backbenchers had hoped the government would similarly retreat from the worst of these reforms. So far, they have been disappointed.

The government’s announcement praised its own generosity for introducing a three-month period before benefits are phased out – but losing half your household income in September instead of June is hardly much comfort. Other changes since the reforms were first mooted have been described by advocacy groups as “the bare minimum”, if that.

The real-world stakes of the government’s reforms could hardly be more real – but this is where we return to the politics, as it’s these that will decide if they actually happen or not, and usually governments find that benefits are a low-risk place for chancellors to find savings.

This might be different. There is very little appetite among Labour MPs to either vote for or defend major cuts to disability benefits, especially when they are obviously a cost-cutting measure. The government’s efforts to rebrand the reforms as mostly about improving the system for disabled people are failing – the same plan can’t be launched twice with entirely different rationales.

The way these reforms work makes things more difficult for government, too: there are some very visible and well-known celebrities and advocates with conditions like Parkinson’s who are capable of making a lot of noise in the media. People with disabilities are often invisible, but the government’s cuts are targeting groups among the more able to be their own public advocates, adding to the political price.

Crucially, the government has also shown that it will cave if it comes under enough pressure for enough time. It has decided that taking £200 a year in Winter Fuel Allowance from people on £30,000 is too politically painful. How can it defend taking £10,000 a year from families in much more difficult circumstances than that?

If the government wants to make these reforms stick, it is likely to have a major battle on its hands. Crucially, it is a battle many of its own MPs, staff, and supporters don’t want it to win.