If Things Can Only Get Better was the optimistic anthem of New Labour’s first term in government, Keir Starmer’s administration has seemed to be ruled by a more downbeat mantra: things can always get worse.

Surely no government has ever gone so quickly from landslide victory to permacrisis. What could be its final stages are now playing out in Downing Street, and on the streets of Gorton & Denton. On a visit there while Starmer battled for his job, the talk was of how things had gone this sour this fast.

Within weeks of taking power, Starmer’s No 10 was embroiled in a bitter civil war between Morgan McSweeney and his first chief of staff, Sue Gray, played out across the national newspapers. Then an ill-judged decision to announce an end to universal winter fuel allowance – a story allowed to lead the headlines for the whole 2024 summer recess – ended hopes of a honeymoon. Starmer’s premiership started badly and never recovered, as is acknowledged by his catastrophic personal ratings and the party’s dismal standing in the polls.

All of which is to say that calling something Starmer’s worst week yet is no light statement, given there have been many dreadful ones – freebie scandals, repeated u-turns, the “isle of strangers” debacle, and the loss of the Caerphilly and Runcorn by-elections – to name but a few.

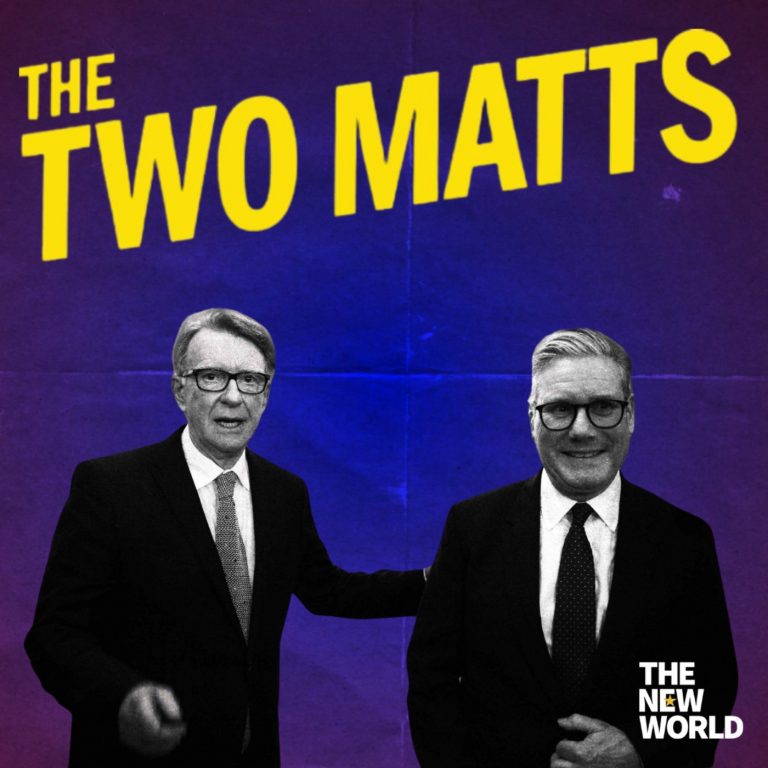

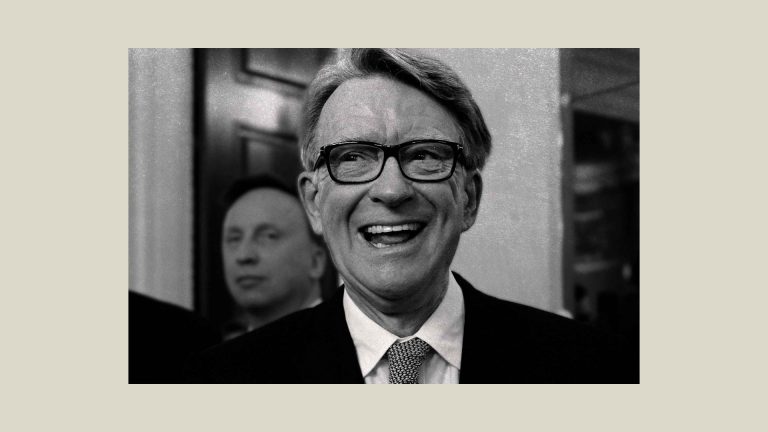

Nonetheless, the fallout over Peter Mandelson’s appointment easily surpasses all of those. On Sunday afternoon, chief of staff Morgan McSweeney bowed to the inevitable and announced his own departure. On Monday, it was No 10 PR guru Tim Allan.

At the time of writing, Starmer is still prime minister, but even his supposed allies are discussing whether he will last the week, never mind get to the Gorton & Denton by-election on February 26, or the May 7 local elections that were supposed to seal his fate. No-one believes he will be prime minister at the end of 2026, let alone by the time of the next general election. Starmer is mired in a scandal he cannot shake, with more unavoidable bad news headed his way.

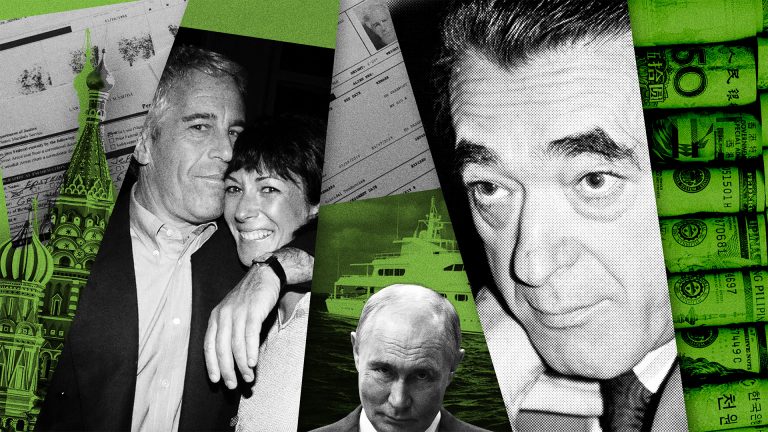

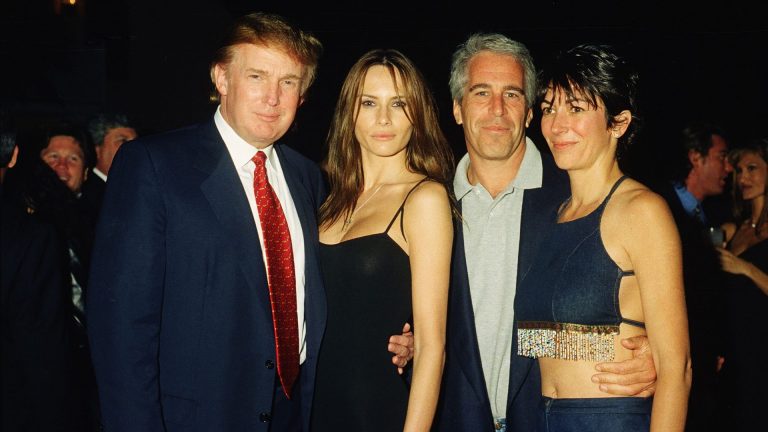

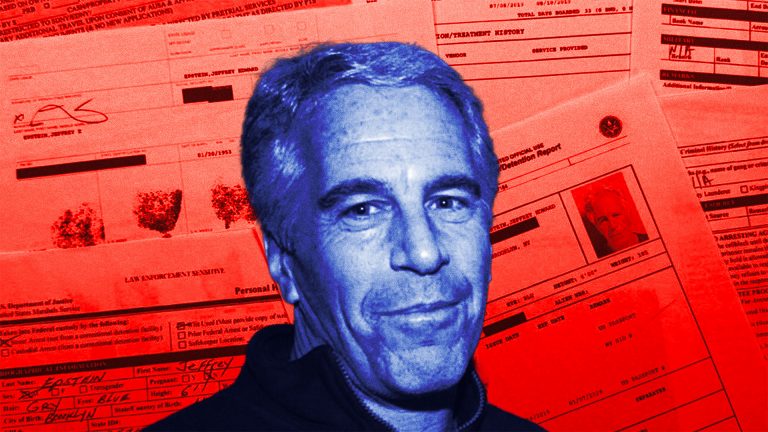

McSweeney was, in essence, collateral damage in an ongoing US political row. Key figures in Donald Trump’s administration spent months promising to reveal “the Epstein files” after making lurid claims about how they would implicate Democrats in endless crimes.

After reporting revealed Trump himself was regularly named in those documents – including having written a sinister birthday message shaped like a naked young woman or girl – the administration’s enthusiasm for disclosure all but disappeared. Congress then forced the Department of Justice to release the files, and since Christmas, some three million have been published.

Mandelson was not on anyone’s mind when they were pushing for the Epstein files’ release – but he and McSweeney are, so far, the most prominent global casualties of the renewed scandal. Mandelson had already lost his job, but now faces criminal investigation and the destruction of his reputation. McSweeney, who never even met Epstein, had to go as a result.

It is a clear reminder: once documents are being disclosed, the fallout is hard to measure. Now, Starmer has been forced by parliament to disclose what could be up to hundreds of thousands of documents relating to Mandelson’s appointment as ambassador and time in the role. There is no way to predict just how damaging those will be, nor exactly who will find their career in tatters by their end.

Starmer has few ways out of this. He cannot stop the release of the documents, he has no-one prominent left to blame for appointing Mandelson other than himself, and he has few ways of moving the story on short of resigning himself.

Suggested listening

Face it, Keir, it’s over. But you could still save the nation

That is one unavoidable media storm of the next few weeks. The other comes in the form of an electoral challenge: the by-election in the Manchester seat of Gorton & Denton will focus the minds of Labour MPs on what the government’s performance means for their own job security.

Depending how you measure it, Gorton & Denton is either the 38th or the 57th safest of Labour’s 404 parliamentary seats. That means that at least 350 or so Labour MPs are aware that their seat is, on paper at least, more difficult to hold than this one. Losing a seat like this is existential for Labour – if they can’t win here, they can’t win anywhere.

Gorton & Denton is a particularly obliging seat for anyone wanting to evaluate how Starmer and McSweeney’s strategy for Labour is working. By their very nature, by-elections often tell you little about the national political picture. There is only so much an English shire constituency, for example, can tell you about Labour’s prospects in cities.

This one, though, is different. Labour nationally is facing fierce competition from two political flanks. On its left, it faces a resurgent challenge from the Green Party and its new leader Zack Polanski. On its right, Reform has surged to the top of the polls, mostly by taking votes from Conservatives, but also by attracting some older white working class voters who once voted Labour.

Under Starmer, following a strategy widely believed to be McSweeney’s, Labour has focused relentlessly on the threat from the right, while all but overtly insulting the left and its values. Starmer has intermittently called out the racist dog whistles of Reform, only to have his ministers endlessly announce new crackdowns on “illegal immigrants” and new ways to make the lives of asylum seekers more miserable.

The theory of the case was that would-be Reform voters had to be given as much of what they wanted as Labour could deliver, while those deserting in droves to the Greens could be given nothing – with McSweeney believing that they would nonetheless return to voting Labour at the next general election, just to stop Nigel Farage becoming prime minister.

Obligingly, Gorton & Denton offers an almost perfect test for how that strategy is going. The constituency is not so much one cohesive area as a series of smaller communities shoved together in the last boundary review to make a seat of roughly the right size. That the constituency is physically bisected by the M60 motorway makes that metaphorical divide physical.

To the east of the M60 is Denton, the older, whiter, and somewhat poorer section of the constituency, and the most obvious target for Reform. Matt Goodwin’s campaign is set up in a warehouse on an industrial estate at the edge of Denton – and the core of Reform’s bid to take this seat lies in this area.

The bulk of the seat, though, lies to the west on the M60. A key battleground here is Levenshulme, once a white working-class area that has over the last 60 years seen three influxes of immigration. In the 1960s, the area had a wave of Irish immigration. In the 1990s, British Pakistanis started moving to the area, and in the last 10-15 years the hipsters – students and young graduate workers displaced from Manchester central by house prices – have moved in.

This diversity is impossible to miss on Levenshulme high street. In the course of 100 yards or so, you can move from Bia Café Bar, which still plays traditional Irish folk music at weekends, via pubs serving £2.45 pints, to the bleedingly cutting edge wine bar Isca, founded by the former sommelier of the much-lauded green Michelin-starred Where The Light Gets In restaurant. As you do, you’ll pass MyNawaab, an all-you-can-eat restaurant that does a roaring trade catering for Asian weddings.

The area wears its diversity on its sleeve, and its different communities exist right on top of one another – seemingly without trouble. This is what Labour’s modern heartland looks like: its core vote in 2024 was made up of students, young professionals, and ethnic minority voters.

But while Labour faces a challenge from Reform in Denton, it faces at least as aggressive a challenge from the Greens in Levenshulme – their posters are everywhere, as are their canvassers, and they are almost as determined to beat Labour as they are to beat Reform.

Gorton & Denton is a must-win for Labour, whatever happens to Starmer. If they cannot win this seat, they are looking at a general election disaster on the scale of that faced by the Tories in 2024. But more than that, it highlights the risks to their coalition.

Suggested Reading

Mandelson in hiding: A ‘New Yorker’ profile

If the Greens win the seat, the idea of Labour as the most viable “stop Reform” vote could disintegrate entirely. If the Greens can win a seat as safe as this one, why would Labour be the obvious place to vote tactically elsewhere?

But the flipside risk is clear, too: if Labour and the Greens fight it out to a draw, they could split the stop Reform majority that exists here, and allow the extremist Goodwin to become an MP. The stakes are high.

Labour is certainly not letting the seat go without a fight. When I visit, its campaign HQ for the day is located in the Jain Community Centre in Levenshulme, and activists are constantly bustling in and out for leaflets or direction.

That morning, they were fired up by a live performance from Manchester rock band Inspiral Carpets and a speech from Manchester mayor Andy Burnham – who despite being blocked from standing in the seat, has nevertheless, activists say, campaigned in it at least three times in the last week alone. He seems determined to be the very model of a good sport doing what he can to help the candidate. Today, Angela Rayner is also up and campaigning in the seat. Most of the cabinet have already visited, though notably not Keir Starmer himself.

The Labour team stress that Manchester Labour brand and identity – a Labour MP, they note, can fit in and get things done with Labour councils and a Labour mayor. None quite say it, but the stress on the word “Manchester” emphasises it for them: they’d rather not talk about Westminster.

The next day, I speak to Angeliki Stogia, Labour’s candidate in the area, who has been a councillor since 2012. She has been receiving online abuse for not being a true Mancunian – she was born in Greece – but insists it is not slowing her down. “I’m a proud Greek woman,” she says. “I came here 30 years ago. You know, there’s a poem that says that some people are born here, some people are drawn here, but we all call it home. I was drawn here.”

I ask whether Labour’s national woes are hurting her campaign – suggesting they certainly can’t be helping. “It’s interesting, the national picture,” she starts to reply before pausing for some time. She then agrees that it was right for McSweeney to resign, adding of Mandelson himself that “he’s disgraced himself, and he’s let the country down, and people are rightly asking questions”.

Stogia’s pitch is that she’s been in Manchester for a long time, and worked for it a long time. The Greens have no councillors in the constituency, she notes, and in Manchester proper voted against affordable housing just last week. Reform’s candidate, despite claiming local connections, has not lived anywhere near the seat for years.

The message on the ground in Gorton & Denton is to focus on Manchester. For Labour nationally it shows up the weaknesses: a win is nothing to be celebrated, as this should be a safe seat. Even if Labour holds the seat, the credit will – deservedly – be given to Labour’s formidable Manchester operation, not the national party. And a loss would be calamitous.

Again, Starmer has to get through the Mandelson files and the Gorton & Denton by-election just to survive February. His prize for that is getting to May’s election, in which Labour is expected to lose Wales for the first time in a century, and lose councils across the rest of the country.

Starmer has no chief of staff and, following Tim Allan’s departure after just five months, no director of communications either. He has an endless procession of rakes to step on. He has no obvious or viable ways out.

Starmer is a notoriously stubborn and ambitious man, and he has always insisted he would fight to hold the premiership until the bitter end. He must surely be looking around and wondering two things.

First, what is it that he’s holding on for? And secondly, if this doesn’t qualify as the bitter end, what situation possibly could?