Helen Lewis is in demand. She’s a staff writer at both Private Eye and the Atlantic and a regular on Have I Got News For You. As we sit down to talk, she’s getting ready to attend the Paul Foot investigative journalism awards, for which she was a judge. And at some point before the end of the evening, she needs to do some research for her BBC Sounds podcast Strong Message Here, which she co-hosts with the satirist Armando Iannucci.

Somewhere among all of this, she’s found the time to write a book, The Genius Myth: The Dangerous Allure of Rebels, Monsters and Rule-Breakers. History is full of stories of great men – and they’re almost universally men – who see what others cannot, and who propel humanity forward as a result. Yet Lewis is out to challenge not just the level of brilliance we load on to scientific or artistic geniuses, but the very concept itself – noting its troubled history with eugenics, the bizarre modern-day dramas of ultra-high-IQ societies, and the pressures put upon those given the “genius” label.

Lewis contends that “genius” is a story we collectively tell ourselves to help make sense of the world. Saying something is all about the story is always convenient for writers, who make their living crafting narratives, which she can’t help but note.

“That’s the sad conclusion of almost all of my journalism,” she says. “That politics is about stories. History is about stories. Genius is definitely about stories.”

There are essential elements to the story of a genius which we all need for the tale to be satisfying to us, she continues. One of these is that genius has to come with a cost – isolating the genius from people around them, or otherwise taking a physical or mental toll. Lewis cites Michelangelo damaging his neck for eight years to paint the Sistine Chapel, or Aaron Sorkin burning himself out on cocaine to write seasons one and two of The West Wing virtually solo.

“It’s true that most high achievement does make incredible demands of you,” she says. “But I also think it’s a bit of an explanation for the rest of us about why we haven’t made those high achievements, right?

“The line I think about more than any other in literature is Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Pride and Prejudice, where she sees Elizabeth Bennet playing the piano quite badly, and she says, ‘had I ever learned I should have been a great proficient’.

“This is a perfect line, but I think that’s how most of us, intuitively, would like to feel to sort of repress our jealousy about geniuses. It’s that ‘well, obviously, weird people, sad comedians have to go on stage, but I don’t have to do that because I’m normal and well adjusted’.”

Our idea of genius, then, has less to do with the people we bestow that label upon and more to do with the rest of us – it’s how we reconcile ourselves to a life without that level of accomplishment. Lewis’s timing with The Genius Myth, though, feels suspicious.

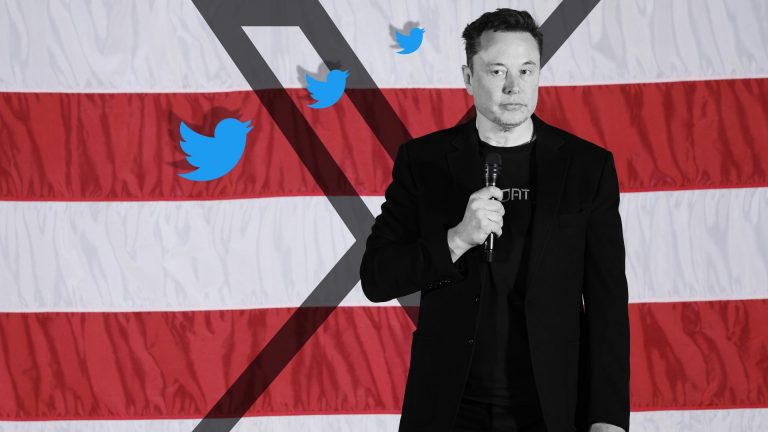

It comes at a time when much of the world’s discourse is dominated by one man who was seen as such a modern-day genius that the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Tony Stark was based on him. Until recently, Elon Musk was known to most people as the man who had “solved” electric cars, space launch, satellite internet, and perhaps even mind control through brain implants.

Today, as Tesla sales are in freefall and his bizarre rants on the social network site he bought for $44bn are all too visible, the idea of Musk as the infallible polymath is impossible for most of us to sustain. The genius who doubles up as the world’s richest man engages in a prolonged public meltdown. That surely cannot be a coincidence.

One thing Lewis thinks we miss about Elon Musk – in part because we write neat “just so” stories about the lives of geniuses after they reach the top – is the role of dumb luck. “Elon Musk is undoubtedly a very smart guy, and one thing that Walter Isaacson’s biography of him says is that he’s this risk-taker.

“But that becomes a fallacy, though, at that point, doesn’t it? Because it’s like all the other one thousand people who also took extreme risks like he did and failed, well, we don’t write biographies about them,” she contiues. “So, he’s got to that stage where he’s become successful, and he thinks it was preordained all the way through, and he doesn’t see all the points at which it could have gone wrong for him.”

Suggested Reading

Why we should all game-shame Elon Musk

Lewis argues, though, that her book is hardly necessary for puncturing the “genius myth” around Musk – he did that for himself when he bought Twitter. “The myth of this guy – if you watch the BBC documentary about him, or lots of the reporting about him – is that he was so dedicated,” she says. “‘He just works all the time’. ‘He just sleeps under his desk’. ‘He just has this incredible focus’. And you go, I can see the tweets. I can see the fact that he tweets something like once every three minutes, on average, 18 hours a day.”

In the conclusion of her book, Lewis contends that we should tell ourselves a different story about genius – instead of thinking of it as a label applying to particular people, we should go back to its original, classical, conception of being a period of inspiration – something that happens to you for a period, rather than something you are.

That’s a nice idea, but not how a book challenging the idea of genius is likely to be read, I suggest. Isn’t this going to be read as a “woke” book challenging the idea of male brilliance? “What I really enjoy is the fact that people criticise me from so many different directions,” she says.

“So you’re right. There’ll be people who think I am like a woke feminist who hates great men. And then there will also be people who’ll think – because I’m not completely environmentalist on IQ – that I’m, you know, a terrible reactionary… I now get criticised in America for being conservative and also overly liberal, and I get criticised for being a Terf and I get criticised for being insufficiently Terf-y. And that… that’s fine.”

Lewis’s delight at being lambasted by all sides comes across as absolutely genuine. She has been a favourite target of the manosphere for nearly a decade, as a prominent feminist who interviewed Jordan Peterson in 2018 – an encounter about which he still publicly complains, years later. But in the UK she was one of the first writers to publicly challenge trans activism from a feminist perspective – hence her labelling as a Terf, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist – and in America, she was one of the earliest writers to question some of the excesses of the racial reckoning that followed the Black Lives Matter moment.

Does she pick these fights deliberately? Not always, she suggests. The BLM piece in the Atlantic focused on a row at the Guggenheim Museum in New York between its longstanding white chief curator and a black Basquiat scholar. She was assigned the piece by an editor, rather than finding it herself. “You’ve got time to do this, frankly, because other American publications won’t touch this story,” Lewis says she was told.

Suggested Reading

Mussolini, Trump and me

The art world, Lewis notes, works “a bit like medieval cardinals or nobles… it’s dead men’s shoes” – to advance, you need to topple some of the figures occupying the handful of top jobs that exist.

“Whatever the weapons are to hand, people will use for their advancement. And so in the same way that in the 15th century, you would have accused your rival of heresy and being secretly Protestant, and then had them burned at the stake, what you did in 2020 was accuse them of being racist.”

This, she argues, contributed to the racist backlash that has engulfed America and helped to re-elect Donald Trump – most people who supported BLM did so sincerely, but it’s absolutist rhetoric that if you’re not anti-racist you’re a racist caused some people to spin off in the opposite direction.

Lewis says she saw a similar trend in the trans debate, an issue she wrote on “between 2014 and 2019”, but has rarely touched on since. “It was the ‘no debate’ era. Stonewall said ‘we’re pushing for these big changes in the law, but also, if you disagree with us, you are such a bigot, we can’t be on the same stage as you’,” she says. “I’d be talking about how toxic the media debate was, irony of ironies, and I just think that was a really difficult time to write about it.”

Things changed, she says, when the political right saw the argument as an “80:20 issue” on which the left was on the 20% side – suddenly, it became very rewarding to write from a perspective critical of the expansion of trans rights.

Lewis notes that there was a positive flurry of articles “saying ‘oh you can’t say that’” on trans issues whose very existence proved the opposite: “You could say that,” she says. “You could say that in the Telegraph, in the Mail, in Unherd, in the Critic, in wherever it was, and just at that point, it automatically becomes less interesting.”

Lewis feels she has gone from being seen as radically anti-trans to getting attacked from “her” side of the issue for being insufficiently hostile to trans people – she believes in social transition, she says, and uses the preferred pronouns of trans people. The gender critical activist base has shifted while she has stayed where she was, she argues – largely because she doesn’t stay on the same issue for very long.

“I have a real hatred of saying the same thing twice, which the modern media environment doesn’t really reward,” she says, whether it’s on trans rights, BLM, or anything else. “It rewards you for having one thought and then saying it out loud over the course of several months, 500 times.

“But I’m not an opponent for BLM. I do think that America needs to come to terms with its racial history. I do think the legacy of America’s historic racism is still felt in the lives of black people in America today. I didn’t want to become a kind of anti-woke activist. I just wanted to find a really great story about excess, and I found it.”

This attitude means Lewis doesn’t even feel comfortable identifying among so-called heterodox thinkers, or the group once identified as the Intellectual Dark Web by Bari Weiss – most of whom have gone on to become Trump supporters and culture warriors. Lewis is clearly appalled at the idea of playing to a crowd, cheering her on.

“I just feel like if I was airing really basic opinions that were tossed off to applause… it’s lazy,” she says. “It’s like when comedians stop getting laughter and they start getting clapped instead. It’s the journalistic equivalent of clapter.”

Almost all criticism, then, seems like water off a duck’s back to Lewis – but one thing does still get to her, and it is an awkward one for a woman who has just written a book on genius. “For me, it’s definitely people saying that I’m stupid because they disagree with me – which I often find really sexist, right? – It’s like, ‘Who’s this dumb bitch?’”

Has Lewis made a mistake revealing to her haters how to wind her up? “No, because I need to get over it,” she concludes. “It’s completely irrational at this point in my career to still be worried about random men on the internet saying ‘who’s this silly girl?’ when I’m 41 years old.”

As Lewis gets ready to dash to her awards ceremony, I throw in a final question – what about the opposite? She’s written a book about genius, after all. Is she perhaps hoping someone might throw the label in her direction?

“I don’t think anyone’s ever called me a genius, I think I’ve dodged that bullet quite successfully in my career so far,” she says, but if someone does, it would get pride of place – in her downstairs loo. “It can go next to my Ralph Steadman cartoon of Paul Dacre and my Martin Rowson cartoon of a vagina. That’d be the third in a great triptych.”