The biggest crises hide in plain sight. The evidence is there, the stories are reported, any of us could do more about it, but we don’t.

The cuts made by Donald Trump and Elon Musk to the USA’s overseas aid have already claimed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 lives across the world – six to 10 times the death toll of Gaza – and get a fraction of the attention of Trump’s day-to-day chaos. We’re similarly blind to the deadliness of our streets: road accidents kill 1.2 million globally every year, while air pollution shortens seven million lives – but most of us worry more about street crime than either of these.

Climate change, though, is perhaps the ultimate example of a crisis we all know about and yet do less and less the closer it gets. There is every indication that we are reaching a point of no return that will lead to not just ruinous environmental damage over the long term but in disastrous short-term effects on insurance and other financial markets.

Last week, a new report by an international team of 60 climate scientists revealed that we have less than two years’ “carbon budget” left if we hope to keep global warming to less than 1.5 degrees. In other words, in two years’ time, unless something miraculous changes, we will have blown past the 1.5-degree target, the best hope of avoiding major changes to global climate. If instead we keep to a 2-degree threshold – an estimate of where we must be to avoid truly seismic changes to life as we know it – we have about 20 years of emissions at our current rate left, before we have to zero things out.

Every week, some new piece of evidence emerges that we are running out of time to avoid disaster. Almost as often, we see the early signs of what those disasters will look like: extreme weather events are up, polar ice (despite claims to the contrary by “sceptics”) is vanishing, and wildfires get worse every year. We are already starting to live through the effects of climate change.

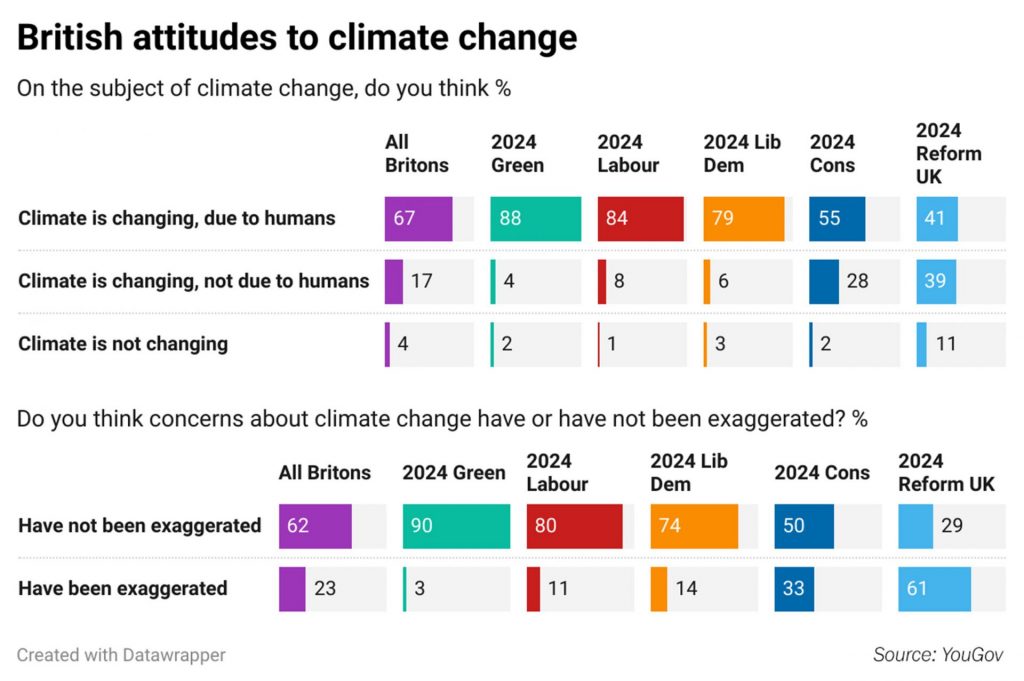

And yet, despite all of this, the nearer we get to calamity the less we seem to care about it. According to YouGov, 67% of Brits agree with the statement that “climate is changing, due to humans”, versus 17% who agree it’s changing but think it’s not man-made and 4% who think the climate isn’t changing.

That’s a sizeable majority, but it’s not nearly as big as it should be – and inevitably, it’s polarized. 79% of Lib Dems, 84% of Labour voters, and 88% of Greens agree that climate change is happening and man-made, versus just 55% of 2024 Tory voters and 41% of people who voted Reform.

Similarly, 33% of people who voted Tory in 2024 think climate change is exaggerated, as do a massive 61% of Reform voters. The result is that public and political support for action to tackle the biggest crisis facing humanity IS is ebbing, just when it’s most vital.

IN PICTURES/GETTY

YouGov has asked voters since 2019 whether the government should increase or reduce spending on tackling climate change. Until April 2024, every single poll showed more support for increasing spending on climate change than reducing it. Since then, every poll has shown the opposite – today, 29% of voters want to spend less tackling climate change, versus just 17% who want to spend more.

Similarly, the number of voters listing climate change among their top three issues for the country has plummeted, with only 15% of voters ranking it on their list. Amazingly, only 51% of Green voters included climate change in their top three, followed by 21% of Labour voters, 18% of Lib Dems, 7% of Tories and just 5% of Reform voters.

There are certainly no shortage of more immediate crises to take our attention – while the worst of recent inflation has passed, the cost of living is still tight, and we seem to bounce from one international conflict to another. The public can surely be forgiven for having our heads turned, but that only enhances the need for politicians to lead – to separate the urgent from the important in a bid to avoid disaster.

Instead, the UK’s right is trying to treat climate change as if it is just another culture war issue that can be shrugged aside as “woke”. Reform UK is predictably the most extreme on this, trying to raid climate projects in a vain attempt to make their nonsensical spending plans add up even for a moment.

But the Conservatives, feeling threatened from the right, are doing much the same – suddenly opposing initiatives they supported as government ministers just months ago, making it feel able to trivialise the issue in a way that will surely look dreadful with even a decade or so of hindsight.

The government, at least, has a capable figurehead for its energy policy in the form of Ed Miliband. Within Westminster, the former Labour leader is rapidly becoming a hate figure on the right on the scale of Jeremy Corbyn, with once-moderate Conservatives privately denouncing him among themselves as a climate extremist – a sign of the polarisation taking place online and behind closed doors.

But in reality, and despite some internal briefing against him from his own side, Miliband is getting through a serious course of action on climate change among the froth. His is the environmentalism of action, not protests: serious investment in green energy, heat pump regulations, and widespread insulation programmes.

They may not be the stuff of which songs are written, but Miliband has secured the investment he wanted and is now counting on it it will pay dividends. In the short and medium term, winning looks like energy bills going up less slowly, in more green jobs and investment, and in similar measures. In the longer term, it is all about the global thermostat.

Labour once felt so confident in Miliband’s green energy programme that they were going to make it the centrepiece of their governing philosophy. The Green New Deal was believed to be a vote winner (and even now its policies test well). In just a year of government, it has turned into a success story that no one in the party wants to talk about publicly.

Keir Starmer is famously a political manager rather than a philosophical leader, and he has adopted nearly as many different visions for his governments as he has missions, milestones and priorities – not least because it seems to some as if No 10 keeps changing the vision whenever the polling numbers move.

Suggested Reading

Has the ECHR overreached on climate change?

The UK’s position could be far worse: there is still steady progress on the climate agenda, but it is now having to happen behind the scenes, and no longer has a political consensus to protect it – a change of government could stall it entirely. When the loss of political will is mirrored across the world, there are reasons to grow worried that as the consequences of climate change become ever more real, our response to it gets less and less serious.

It may be the case that markets do what politicians cannot. The insurance industry underpins the global economy, and it is incapable of ignoring climate change: if it does not update its models, it is on the hook for billions if not trillions of payouts. Homes are becoming uninsurable due to fire or flood risk. Soon, that will be whole regions.

Where insurance is today, other financial markets will be tomorrow. The sums at stake are simply too great for traders to engage in the same game of denial as the politicians are playing – but that could make the coming clash all the worse.

Politicians are abandoning climate just as the markets are facing its reality. The showdowns between Liz Truss or Donald Trump and the markets felt like high drama. They may be a mere warm-up act versus what could be to come.