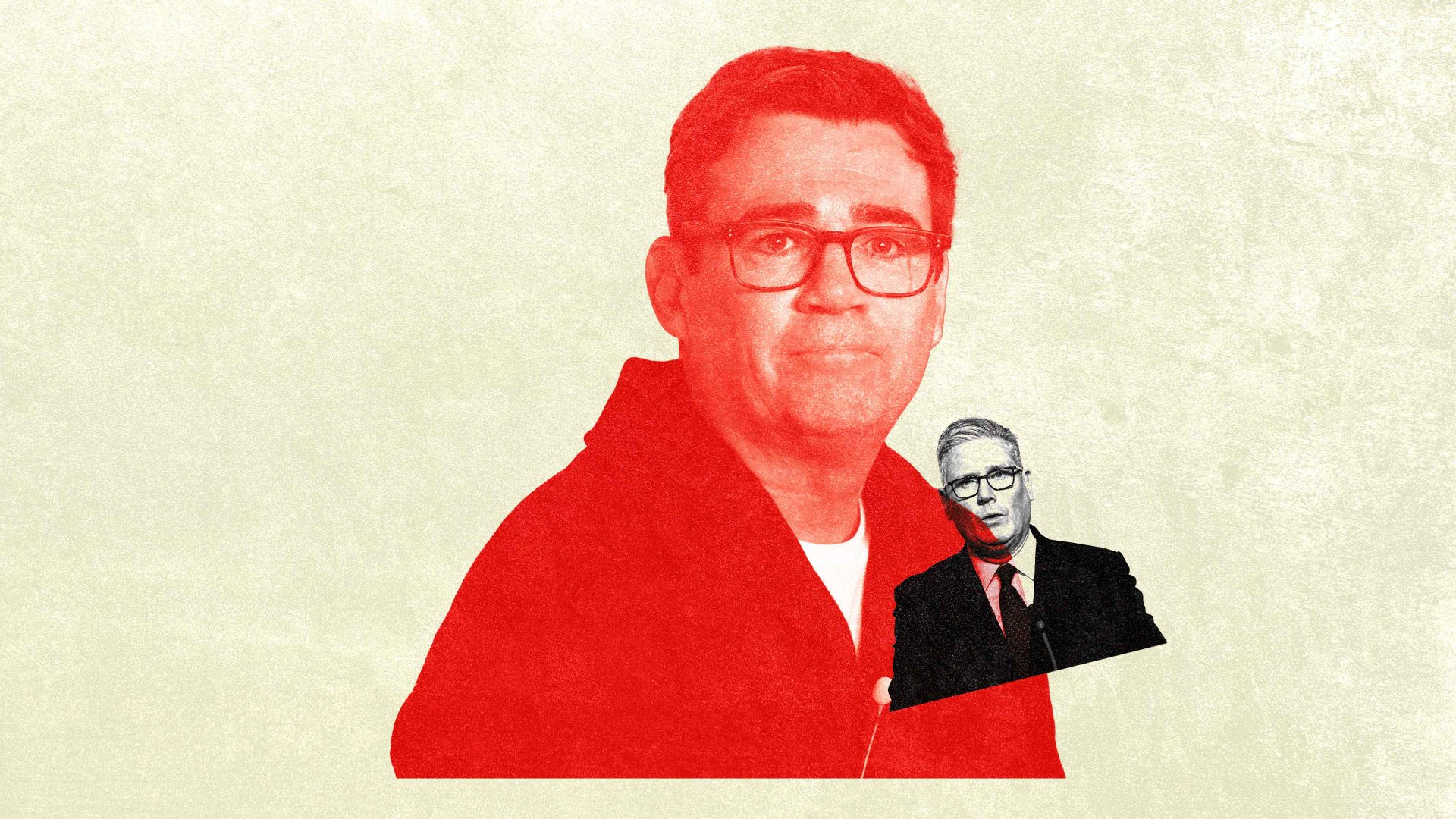

It is difficult to present yourself as the saviour of your political party when you can’t even get selected to run for a seat – but that’s the position in which Andy Burnham finds himself after his second apparent challenge to Keir Starmer in six months appears to have fizzled out as rapidly as the first.

Burham’s furious supporters say No 10 is behind the decision by a subcommittee of Labour’s ruling National Executive Committee to block him from standing in the forthcoming Gorton and Denton by-election, which he would need to win in order to launch a credible leadership challenge to Starmer later this year. To those not paying close attention, it looks like an outrageous stitch-up.

But things are not quite that clear – and the way things have unfolded may say as much about Burnham’s own weaknesses as they do about a prime minister now being derided as running scared.

The Burnhamites say the Greater Manchester mayor is popular locally and, in the face of a strong Reform challenge, would have a better chance of holding the seat for Labour than most other candidates. By blocking him from standing, they say, Starmer has excluded a rival at the cost of damaging his own party.

But this logic falls apart on closer examination. Burnham already has a job – he holds the second-largest mayoralty in the country, leading an area with a population of almost three million. He is less than halfway into a term he promised to serve in full.

Crucially, he cannot continue to do that job if he stands to be an MP: it’s laid down in UK law that mayors who oversee their local police forces (which Burnham does) cannot also serve as MPs. It would mean that Burnham running in Gorton and Denton would trigger a much larger by-election – the biggest in UK political history – for the Manchester mayoralty.

That is a whole extra race, requiring time, money and other party resources. For this reason, standing mayors need special permission to put themselves forward as candidates for a parliamentary seat. This is what the NEC refused over the weekend.

Burnham’s stated logic simply does not hold up: if his popularity would be useful to hold Gorton and Denton, it surely would be more damaging to lose it in the much larger mayoral by-election. Standing to be an MP makes sense if Burnham is looking to challenge Starmer for the leadership, but it doesn’t make sense under any other circumstances.

Given that Burnham openly challenged Starmer at party conference just a few months ago, it is a bit rich to expect No 10 to accept a nonsensical argument that makes it easier for their man to be kicked out of office. Love Starmer or loathe him, it’s a bit much to expect him to actively help a plot against his own leadership.

Suggested Reading

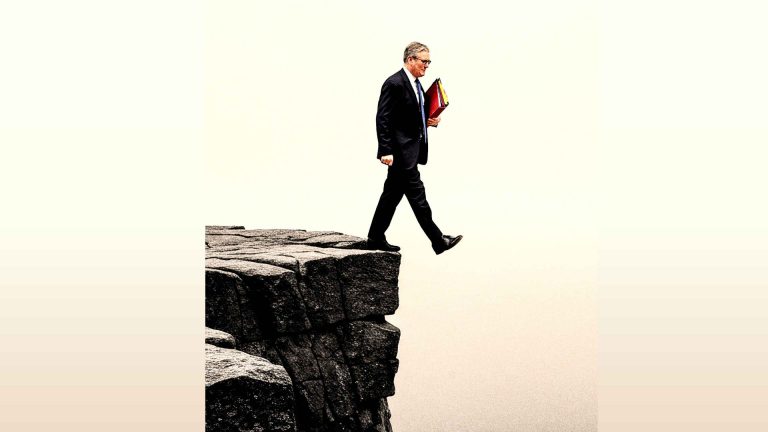

The May elections will be Starmer’s cliffhanger moment

Some within Labour note that the Gorton and Denton controversy further highlights some of Burnham’s own political shortcomings. Even Burnham’s detractors in parliament stress they think he is doing well in Manchester – but quite a few MPs believe he should stay there.

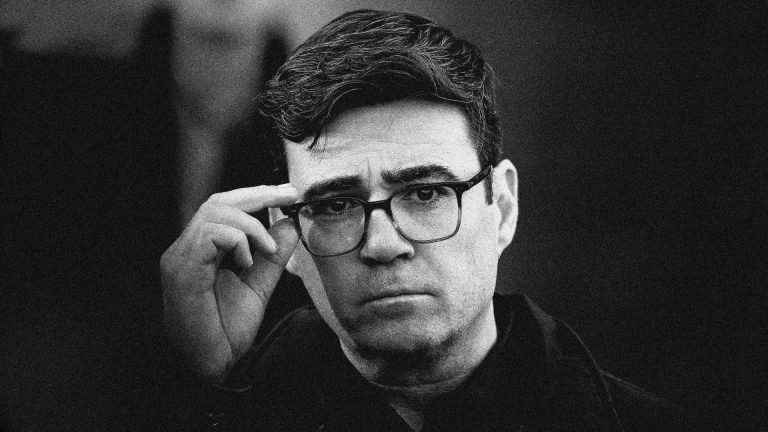

For the first two decades of his political career, Burnham was a consummate Westminster insider who followed the well-worn New Labour track into the Cabinet. He started as a researcher, did a short stint working for outside organisations friendly to Labour, did his obligatory few years as a special advisor, and from there got selected as a member of parliament. He rose to three different cabinet posts, eventually serving as secretary of state for health.

Veteran Labour MPs who remember that era, then, raise their eyebrows when the new version of Burnham talks – as he is wont to do – about how he never liked Westminster and never fitted in there. If that’s what “not fitting in” looks like, they wonder, what on earth do you have to do to fit in?

Burnham ran for the leadership of the party twice, failing to distinguish himself on either occasion. In 2010, he finished fourth in the contest eventually won by Ed Miliband, and in 2015, he came a distant second to Jeremy Corbyn, winning less than 20% of the first-round vote.

What Burnham did next earned him a second set of enemies on Labour’s benches – when things got really bleak for Labour in 2017, he got out of town and decided that Westminster had become “a living nightmare”, which was “antiquated” and “basically dysfunctional”. Once he secured the Greater Manchester mayoralty, he argued “what we’re building here… is actually more important” than anything happening in Westminster.

That’s a lot of ammo for Burnham’s detractors, who tend to stay quiet in public – he is relatively popular among Labour members – but who are vocal in private. They note that Burnham fled when times were tough in Westminster, and left them to rebuild the party after Corbynism.

They note Burnham’s political stances change just as readily as Starmer’s, though with less success, and that his views on Westminster seem to be just as malleable.

The most brutal observation, though, was one MP who pointed out that Burnham has been in Labour politics for two decades longer than Keir Starmer, but is still unable to outmanoeuvre him on internal politics – or to spot that if he wanted to challenge for the leadership, he should have run for a parliamentary seat in 2024.

None of this is good for Keir Starmer, though. Both Labour MPs and Labour members were already at their wits’ ends with him, and this will have pissed off many of them still further. But the reality is that Starmer’s team have likely picked the best of a bad set of options.

Suggested Reading

Burnham’s bye-bye by-election for Starmer

The likeliest outcome of blocking Burnham is a few days of vicious headlines in the Tory press, which will likely disappear as Labour insiders will not wish to generate too much internal conflict in the run-up to crucial elections in May. Kemi Badenoch will turn the screw at PMQs too, just as Starmer was beginning to score points against her over internal dissent and Reform defections.

But allowing Burnham to run would have generated months of headlines about internal drama, and with a huge additional by-election to boot. Looked at in those terms, the decision was a no-brainer.

Keir Starmer is probably no safer in his job today than he was a week ago: if the May elections are anything like the wipeout that’s expected, he will surely face a challenge. It’s just now much less likely to come from Andy Burnham.