Immigration is trending. It has been the political story of the summer, making the “winners” of the season Nigel Farage and Reform. The losers are the rest of us.

Protests outside the Bell Hotel in Epping became a magnet for the media – even if that same media seemed uninterested in the backgrounds of some of those doing the protesting and organising. Meanwhile, far right online agitators tried and failed to incite mass protests time and again – despite their efforts egged on by acres of coverage, with suggestions that “tinderbox Britain” was about to burn.

The Tories popped up to tut about how awful it all was, but whenever they did, they were reminded that the huge rise in net migration, the boom in small-boat crossings and the subsequent use of hotels to house asylum seekers all happened on their watch.

Labour scrambled for the right words. A resurgence of small-boat arrivals overshadowed a substantial fall in overall immigration. And, most recently, an interim ruling by a High Court judge over the Bell Hotel in Epping left the asylum system in chaos, casting doubt over the continued operation of migrant accommodation across the country.

If anything could propel Farage into No 10, it is immigration. It consistently ranks alongside the economy and the NHS as one of the top three issues voters care about. It is intrinsically tied to economic growth, social cohesion and fear of crime.

But fuelling fear of migrants is a dangerous game. Farage is being dragged rapidly into extremist positions even he rejected just months ago. Part of his row with his former MP Rupert Lowe was over Lowe’s open support for “mass deportation” – a policy Farage had rejected since his time as Ukip leader.

But last week, under mounting pressure from the far right, Farage embraced mass deportations, promising to leave not just the European Convention on Human Rights but multiple other human rights treaties to get it done, and to deport refugees back to their torturers.

Labour insiders argue that it has been trying to defuse immigration as a political issue. This clearly hasn’t worked – rhetoric and policy are only getting more extreme by the day. The idea that the system has failed is now deeply ingrained.

At its core, though, immigration is the product of hundreds of thousands of individual decisions – those of people across the world choosing to come here to work, or to seek asylum, and those of the immigration system deciding whether to accept them or not. The reality of that system bears little in common with the one that exists in the imagination of its critics

.

In court six of the Taylor House Tribunal Hearing Centre in central London, people are assembled to decide just one of those cases, of an Albanian man we’ll call Atlin Bardhi (name changed). On paper, he is exactly the kind of “criminal” immigrant Robert Jenrick, Farage, and the British press all warn about.

In person, Bardhi – dressed in a smart navy collared shirt, black jeans and Fila trainers – sweats profusely in the sweltering, airless courtroom as he tries to explain, in broken English, why he shouldn’t be deported.

As Bardhi explains the story, through his witness statement and courtroom interviews, his troubles began in November 2019, when a magnitude 6.4 earthquake hit Albania, killing 51, injuring thousands and damaging some 14,000 buildings – including Bardhi’s home. To get medical care for his father and brother, and to rebuild the family home, Bardhi borrowed €25,000 from an organised criminal gang, intending to repay it through construction work.

Instead, he says, he was first forced into prostitution and then trafficked against his will into the UK, where he was forced to work in a cannabis farm in Reading. He escaped in 2022 – causing criminals to visit his family home in Albania to try to track him down, which led to a rift with his family – and claimed asylum. His lawyer warns that his mental health has deteriorated so severely he may be at risk of suicide if returned.

Those taking the Daily Mail’s portrayal of a laissez-faire asylum system at face value would assume this story would be enough to guarantee that Bardhi will stay. The reality is different.

Oddly, the Home Office doesn’t bother to argue with Bardhi over whether or not he was trafficked against his will – a common tactic in these cases, I learn. Instead, they argue, it doesn’t matter. Even if we accept Bardhi’s story on trafficking as fully true, the Home Office lawyer tells the judge in a tone that indicates he certainly doesn’t, it shouldn’t matter. He says that adult men who have been trafficked are not a protected or vulnerable group, so it is safe to return him.

The lawyer continues that Albania has mental health facilities and healthcare, so care can be provided there. He says that while Bardhi claims his family relationships broke down in 2022, he claimed he had good family relations in his asylum interview in 2023.

He points out that it’s six years since Bardhi borrowed the €25,000 but the criminal gang has not troubled his family for it, despite knowing where they live. By the time he sits down, the lawyer seems confident he has poked enough holes in Bardhi’s case to sink it.

This kind of process is what the overwhelming majority of the British public says they want. Poll after poll shows that extremists talking about “closed borders” or “remigration” are a tiny fringe. Most people want legitimate refugees to be accepted, others to be thrown out, and immigrants permitted to work if the UK needs their skills.

The odds are stacked against Bardhi. In 2022, 49% of asylum claims from Albania were successful. By 2024, it was just 9%, and even lower for unaccompanied adult men like him – neither the Human Rights Act nor the European Convention on Human Rights is preventing deportations in these types of cases.

One problem for all concerned is the huge amount of time and effort involved: Bardhi’s case has been pending for over two years since his first interview, and the bundle of documents the judge has to consider is 1,100 pages long. These endless delays cost money, mean many more people need housing at the Home Office’s expense, and keep asylum seekers in limbo.

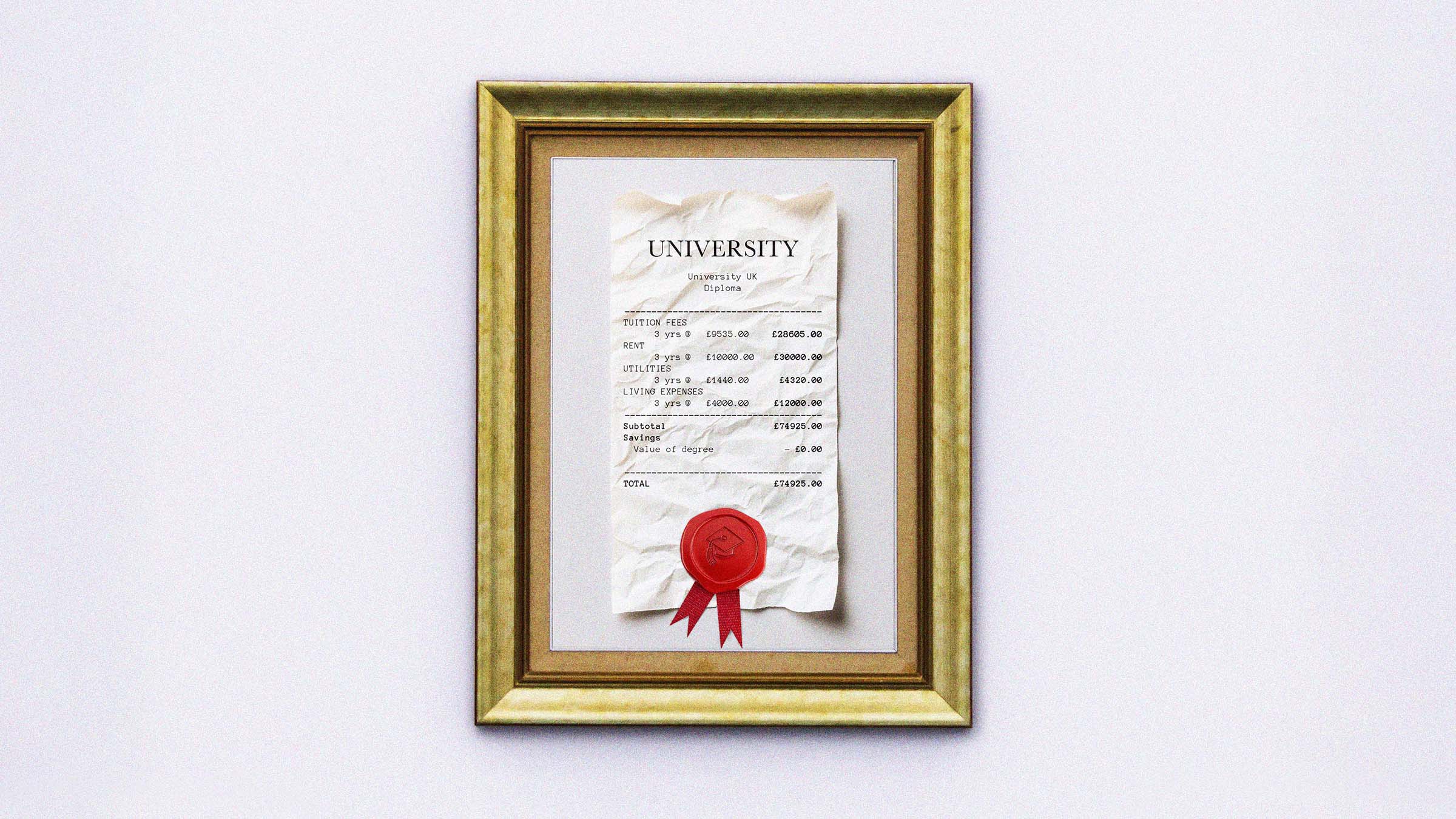

Asylum seekers need somewhere to live while their cases are considered, and when those cases take years that is a considerable drain both financially and on scarce housing resources. Asylum seekers are forbidden from taking paid work, and hotels that were once the pride of a town being used as Home Office accommodation is far more visible to locals than using HMOs or other housing.

Suggested Reading

One-in, one-out is not enough

The cost of asylum hotels last year was £2.1bn, around £70 for every UK household, or four days of the NHS’s running cost. That bill is actually falling – it was £3bn in the last year of the Tory government – but it is still significant. Last weekend, the government said it would unveil plans to “fast-track” asylum hearings, eliminating some of this tribunal process entirely.

Small boats have become the focal point of both the asylum and the immigration debate, in part because they are an almost entirely new phenomenon. Across the entirety of 2018, just 299 people arrived by small boats, rising to 1,843 in 2019. By contrast, during Liz Truss’s 49-day premiership, more than 10,000 people arrived in that way.

There are two reasons that small boats started arriving en masse in 2020. The first is a renewal of conflicts that displaced millions of people, often leaving them looking for sanctuary in Europe. The second is Brexit – once the UK’s exit deal was finalised, it was no longer party to the Dublin procedure, which allowed for the extradited return of asylum seekers to the first EU nation in which they entered.

Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal did not include any replacement for this mechanism, meaning that the UK would be responsible for processing any asylum seekers that arrived via small boat from France – and that France no longer had much incentive to stop people trying. Ever since then, Johnson and his successors have been left floundering for outlandish means to fix the problem he created.

Those of us on the liberal side of politics tend to argue that small boats are a relatively small share of immigration claims, and asylum seekers are vastly outnumbered by people who come here legally to work and study. Both of these are true – and it is also true that two special schemes set up by Johnson for Hong Kongers and Ukrainians led to hundreds of thousands more arrivals than asylum.

But small-boat crossings are substantial and accelerating. It was 1,066 (yes, really) days into Johnson’s premiership until 50,000 people arrived in small boats. To reach the same figure for Rishi Sunak was 610 days, and for Keir Starmer, just 404.

There is also little sense in us as liberals ignoring the fact that immigration and asylum are connected in the minds of many voters to the problems facing Britain, especially when we’re trying to work out how to respond to a movement actively trying to inflame a social problem into a national crisis.

People connect small-boat arrivals, and immigration more broadly, with crime. The reality of this is complex: when it comes to immigration, those born overseas are actually slightly less likely to be convicted of crimes than those born here.

But there is a more specific question to ask about asylum hotels and similar facilities, especially amid the local backlashes caused by specific incidents. So far, the evidence shows that there is an uptick in antisocial behaviour (sometimes referred to as “low-level crime”) around these facilities, but there is no evidence suggesting more serious crimes such as serious assault or a rise in murders around asylum hotels.

The bigger issue is that antisocial behaviour and low-level crime are on the rise generally in the UK. Most people assume that an increase in antisocial behaviour tracks an increase in more serious crime. This is both common sense and logical – if we see vandalism nearby or see security guards in shops, we are likely to feel less safe, and thus assume we’re in more danger.

Moreover, we have been told for decades that antisocial behaviour is connected to, and even causes, serious crime – “broken windows policing” was the mantra of modern policing for decades.

The problem is that it isn’t true. Britain’s streets are about as safe as they’ve ever been, when it comes to violence. Whatever metric you use, serious violence and murder is down, both in the long run and the short run. On crimes like burglary, the statistics are so good they’re unbelievable: burglary is down 90% since the 1990s. But being safer counts for very little if none of us feel the benefit of that, and until low-level crime is tackled, fear of crime will abound.

Claims that immigration is causing the UK to be at “crisis point” are overblown, but they are extremely convenient for a new political coalition. One part of that coalition is the hardcore racists and nationalists, who are seizing upon a new political mood to try to make their previously fringe ideology a reality.

The other part is made up of political opportunists who are happy to give the first group their chance if it will propel them to power. The UK is beset with crises that are difficult but which can be solved if they are tackled boldly, and with tough decisions. Instead of doing that, it is much easier to find a scapegoat for the electorate and blame them for everything.

Suggested Reading

Why xenophobes love flags

The root of the UK’s problems are under-investment in everything, public and private, and under-funding of public services. The UK hasn’t built enough houses for decades, and in the last 10 years has coupled that sluggish housebuilding with immigration in the high hundreds of thousands.

The justice system has been cut to the bone, leaving cases like Bardhi’s taking several years to process – adding hugely to costs elsewhere in the system – and itself serving as a draw for more people to arrive here and work illegally for a few years until they are deported. Policing has been cut, leading forces to prioritise serious crime and leave vandalism out there.

As all of that has happened, the Conservative government – especially under Johnson – used immigration to paper over the cracks, propping up our otherwise stagnant economy, NHS and social care by importing workers. Asylum claims in the UK have never topped 100,000, but net migration peaked close to one million a year.

By keeping the focus on small boats, cynical political operators could both cover up their own negligence, avoid a reckoning with their voters, and pretend that the issues caused by large-scale immigration could be addressed without major impacts on the UK economy, the NHS, and more.

The ugliest aspects of the UK far right are enjoying a resurgence of late, fuelled by overt support from Elon Musk and the algorithms of his social media X, and by the negligent moderation of other social networks. But the overtly racist far right remains a fringe group rejected by the overwhelming majority of the people of the UK – even most Reform voters.

Attempts to get people to take to the streets for protests outside asylum hotels, riots, “general strikes” or any other efforts have delivered derisory numbers – last weekend’s protests totalled around 3,000 people, outnumbered by counter-protesters and totally overwhelmed by the 200,000 people who took part in park runs on Sunday.

Every decade, the UK has faced a resurgence of far right figures. It has faced Enoch Powell and his “rivers of blood”, race riots in the 1990s and the rise of the BNP, and more. This time the far right have the internet, but little else. They would still be eminently beatable, but for one thing.

When Enoch Powell gave his “rivers of blood” speech, he was resoundingly rejected by the political mainstream. Nick Griffin united leaders of every other political party against him. Every time racist parties and neo-Nazis seized upon immigration as an issue, every mainstream party and politician would unite to reject them.

Today, they have quit the field. At best, they say almost nothing, as the government does – parroting a tough line on immigration, doing nothing to denounce the far right, and hoping that this will somehow make the problem go away.

Many mainstream politicians are going further: Robert Jenrick was pictured last week at a rally with a neo-Nazi and a former BNP strategist. A few months ago, that would have been a major scandal. Today, it was met with nothing more than a shrug.

Farage has embraced the nationalist agenda he once rejected, and Jenrick openly wishes to take the Conservative Party in the same direction, while Kemi Badenoch pretends not to notice.

The UK does have a crisis over immigration, but the desperate people arriving on small boats are not at its root. Instead, it is a crisis caused by the collapse of confidence and integrity of the political mainstream – by their unwillingness or inability to confront the malign forces in front of them.

Views that would have got a politician thrown out of their party and out of polite company a year ago are now accepted as mainstream. There is no social sanction to embracing nationalism, xenophobia, or the far right agenda. On the right, it is positively rewarded.

Yes, the actual immigration system needs to be improved and reworked, and the country deserves an honest conversation about immigration and its trade-offs. But none of this will mean anything until politicians regain the courage to call a racist a racist, instead of just vying for his vote. That seems, right now, a distant prospect.