“It was in 2020, when the Black Lives Matter movement was at its height. I was driving past the ‘great wall of Dorset’ – the three-mile-long wall that runs alongside the A31– and I started thinking about Richard Drax and slavery,” says investigative journalist Paul Lashmar, who has just published a comprehensive history of the Drax family.

The author of Drax of Drax Hall knew that behind the great wall lay the palatial Grade I-listed Charborough House, home to Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax (to give him his full title). Until last year, he was the Conservative MP for Dorset South.

Lashmar later discovered that the house and its grounds were just a small part of the 16,000 acres that Drax owns in Dorset. He was, and still is, the largest individual landowner in the county and, until his defeat, the largest landowner in the House of Commons. He also owns more than 2,500 acres of farmland and grouse moor in Yorkshire and a holiday rental property worth over £5 million.

“I knew that the Drax family had originally made their money out of a slavery plantation in Barbados,” says Lashmar, “but since, in his MP’s declaration of interests, there was no mention of his still owning any land there, I wondered when it was sold and to whom. When I began researching Richard Drax I was intending to just do a straightforward audit of an MP and his wealth. It never crossed my mind that the plantation would still be owned by a sitting MP – it would be such bad optics.”

But Lashmar was wrong. Bad optics or not, he discovered (after many months of digging in archives and land registry files in Britain and Barbados) that Richard Drax was in the process of inheriting Drax Hall – a 621-acre sugar plantation in Barbados where an estimated 30,000 slaves lived and died between its establishment in the 1630s and the abolition of slavery in 1833.

The Drax family’s involvement with Barbados and slavery began when Richard’s descendant James Drax landed on the island in 1627, then uninhabited. Initially, so legend has it, James and his companions lived in a cave, eating turtles and hogs, as they cleared the land that was to become the Drax Hall plantation.

Nor were the Drax family just one of a number of British slave owners in the Caribbean, but were, according to historian David Olusoga (in his foreword to the book) “arguably the key players in the origin story of British slavery”.

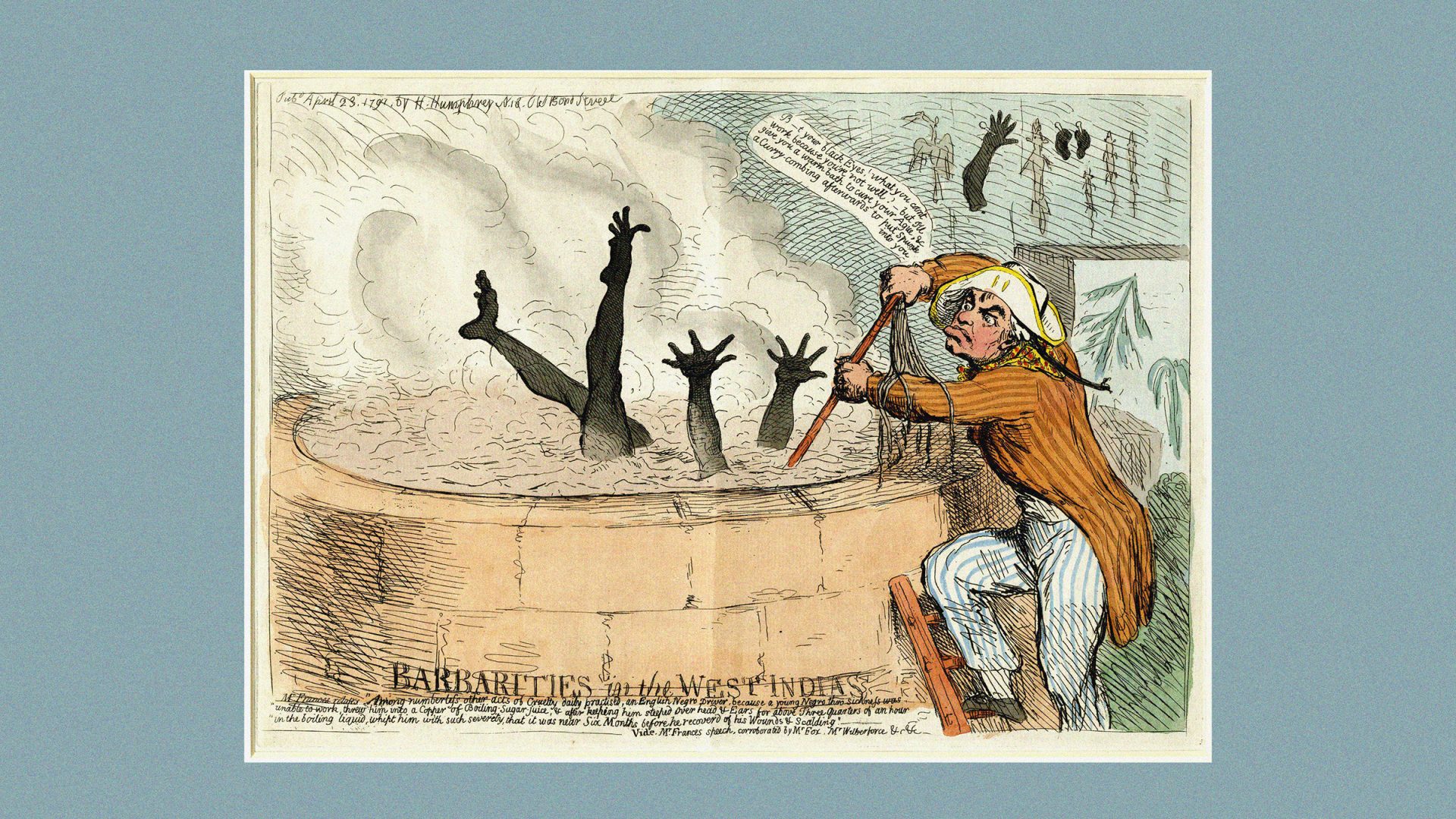

Olusoga makes this claim because, as the book reveals, the Drax family pioneered the commercial production of sugar. James Drax discovered that to make the stuff profitably, and on a commercial scale, would requires “strenuous work under the hot tropic sun” – conditions that were not suited to the European indentured labourers who, until then, had formed the backbone of the plantation workforce.

But these conditions could be tolerated by workers from Africa transported to the West Indies – the first chattel slaves. Chattel slaves, as opposed to indentured labourers, can be bought and sold, they could never attain their freedom and their children were the property of the slave owner as well.

One aspect of the Drax family history that is striking is the extent to which the family have remained embedded in the upper echelons of British politics and society for nearly 500 years. It began at the court of Henry VIII, continued during the civil war and subsequently in Parliament – Richard Drax was the seventh member of his family to sit in the House of Commons.

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, their positions of wealth and influence were enhanced by the profits generated by the labour of their slaves thousands of miles away in Barbados (and, to a lesser extent, in Jamaica as well).

When slavery was finally abolished in 1833, there were 189 slaves at Drax Hall and the Drax family were paid £4,293 12s 6d, the equivalent of £3million in today’s money by the British government as compensation for the loss of their slaves. Now the descendants of the colony’s slaves are calling for the payment of reparations and the Drax family are particular targets.

Sir Hilary Beckles, who chairs the Caribbean Community Reparations Commission, has described the Drax plantation in Barbados as “a crime scene, the killing field of slavery”. He says: “The Drax family has done more harm and violence to the black people of Barbados than any other family.”

Richard Drax has, to date, refused to countenance making any such payments. He has said that his family’s past history of slavery is “deeply, deeply regrettable, but no one can be held responsible today for what happened many hundreds of years ago. This is a part of the nation’s history, from which we must all learn.”

Quite what lessons Richard Drax has learnt from the history of his family’s involvement in slavery is, to date, unclear.

Drax of Drax Hall: how one British family got rich (and stayed rich) from sugar and slavery is published by Pluto Press, £25.