“Sometimes I ask myself,” says Juan Pablo Guanipa, one of Venezuela’s opposition leaders, “who keeps hope alive for those of us whose job is to lift people’s spirits?”

His voice breaks. Just moments earlier, he had been describing how, during last year’s presidential election campaign, he had travelled across the country, even as his wife was undergoing chemotherapy and as friends and colleagues were being arrested or killed. His aim was to spread hope among supporters. “That’s what we’re here for,” he told El Hilo, the podcast of Latin American affairs, when he was interviewed back in January: “to keep people believing that a free Venezuela is still possible.”

After María Corina Machado’s landslide victory in the presidential primaries of late 2023, Guanipa was among those who threw their support behind her and her party, Vente Venezuela. He did this, he said, out of respect for democracy and for the people who had chosen her. A few months after that interview aired, he was detained by the Venezuelan regime under “terrorism” charges. He has not been seen since.

By that time, Guanipa was the last remaining member of Machado’s campaign team still inside the country. The rest had been imprisoned or forced into exile. For months, he had been living in hiding, expecting arrest at any moment. But Machado herself did not leave.

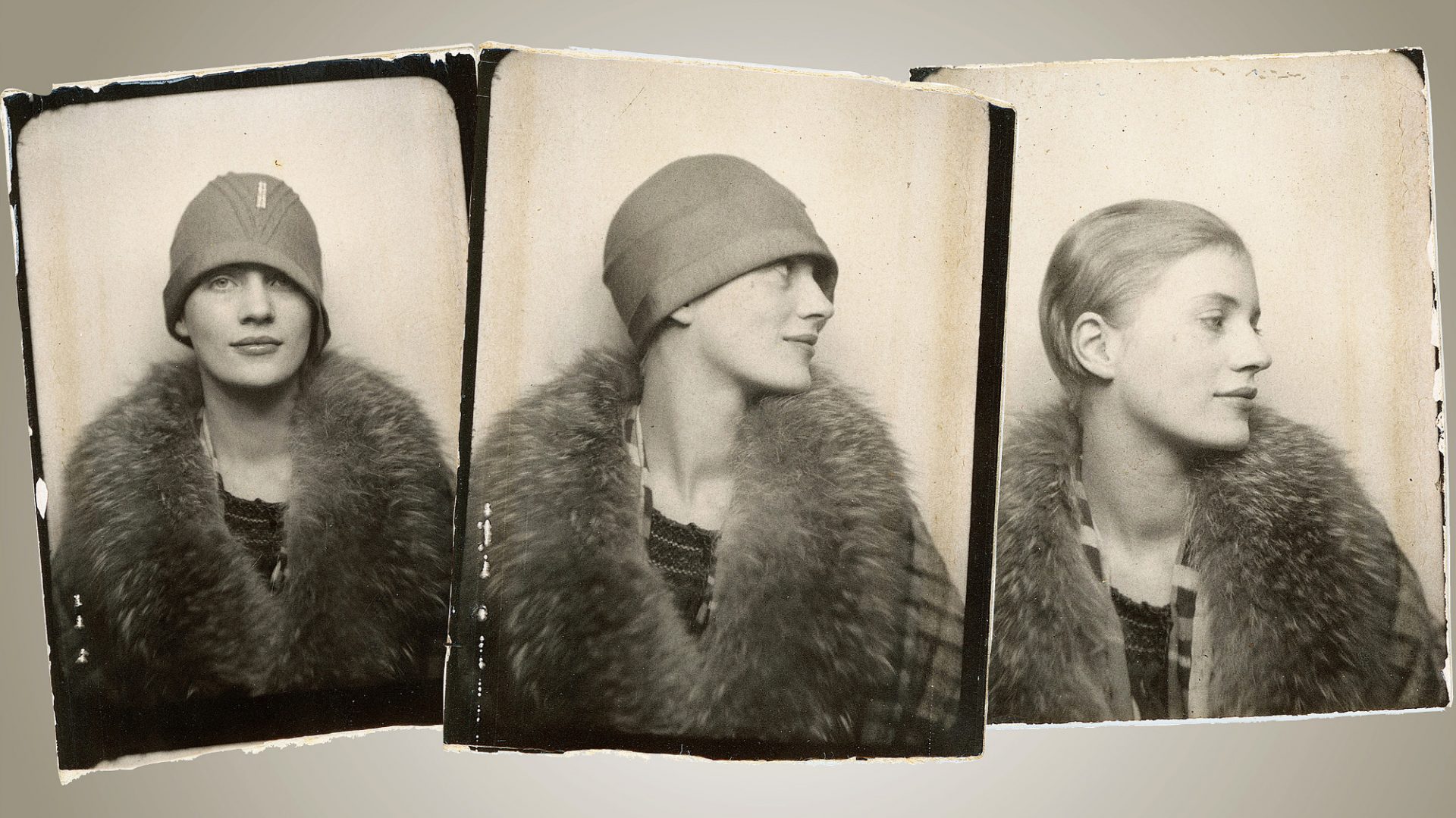

“They wouldn’t dare harm María Corina,” he said. Months later, Machado – the unlikely unifier of a weary Venezuelan opposition – was awarded the Nobel peace prize.

When the Nobel committee announced that she had won, its explanation was carefully phrased, noting that she was chosen “for her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy”.

The committee emphasised her role as a democratic opposition leader – but the citation did not canonise her; it made clear what she had risked, and what she had achieved. There was no speculation on how her politics might evolve in future.

The problem is that Machado does not fit the stereotypical western political view of what a South American democratic politician should be. Her convictions are unmistakably liberal-conservative. She is pro-market and anti-authoritarian, and overall, her political views are rooted in an individualist idea of freedom that contrasts sharply with the state-centric vision that dominates her country. At times, Machado’s rhetoric echoes cold war language about communism and freedom. She is also clear what kind of dictatorship Venezuela faces today: not a military caudillo, but a criminal network that has captured the state itself.

And yet Machado is more than just a liberal-conservative. For more than two decades, she has been one of Venezuela’s most unyielding critics of the regime, in 2002 co-founding Súmate, a voting rights organisation. She was later elected to the National Assembly, but was stripped of her seat after denouncing human rights abuses before the Organization of American States.

Her defiance has been constant, despite threats to her life and the forced exile of her family. When, in 2024, Machado helped unify a fractured Venezuelan opposition and deliver a victory at the ballot box, she became something more than a candidate: she became the embodiment of a nation’s endurance, a channel for the anger, exhaustion and courage that persists behind the despair.

Suggested Reading

Venezuela, the land of permanent Christmas

What she understands and conveys is what many outside Venezuela ignore: that this is no ideological struggle, but a country held hostage by a criminal state. It is no surprise that many Venezuelans rally behind a leader who promises to dismantle the machinery of the state that has suffocated them.

In the months preceding the election, Machado accomplished what many people thought impossible. Though barred from the ballot and threatened at every turn, she remained in Venezuela. She built a network of almost a million volunteers who, at personal risk, monitored polling stations and collected vote tallies, obtaining copies from more than 80% of voting stations and publishing them online. Their data contradicted the regime’s claims of victory.

Still, Nicolás Maduro declared himself president once again, refusing to release detailed results or allow an audit, and jailing 853 people for their role in supporting Vente Venezuela. Even long-time allies were critical of this heavy-handed response: Brazil and Mexico declined to attend Maduro’s inauguration, while Chile’s Gabriel Boric called the process a fraud. Maduro remains in power, now more isolated than ever.

When news broke that Machado had won the Nobel peace prize, the reaction revealed many things, but perhaps most of all it exposed the west’s chronic lack of interest in Latin America. Most major outlets barely cover the region; its politics appear only in fragments, stripped of context, so that when a story like this breaks, there is no framework to make sense of it. The initial reaction was, “at least Trump didn’t win it”, followed by commentary that framed her as a symbol of courage and democratic renewal.

Then, as her alliances with conservative groups resurfaced, the enthusiasm began to tail off. Machado then posted on X that she had dedicated her prize not only to “the suffering people of Venezuela”, but also “to president Trump for his decisive support of our cause”. Mention of the US president changed the wider reaction to Machado. Having finally understood her political character, many western commentators decided that Venezuela’s agony, and the leader of its political struggle, had lost all moral validity.

But that is an unfair misunderstanding. Inside Venezuela, people have been surviving in an oppressive regime for decades. As has been noted by Anne Applebaum, the historian and Atlantic writer, Venezuela is not merely a “failed socialist” experiment. It has become a fully integrated node in a global autocratic web, which she described in her recent book Autocracy, Inc. When western firms pulled out of Venezuela, others rushed in. Russian oil giants like Rosneft, Gazprom, and Lukoil filled the gap left by US and European companies, while subsidised Russian grain replaced imports from the United States and Canada. Gasoline from Russia became the only fuel available in Venezuela, and billions of dollars’ worth of arms and surveillance systems flowed in from Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran.

These were not isolated transactions but parts of a structure that is shared among authoritarian states, one in which Venezuela trades oil, gold, and political loyalty for technology, weapons, and diplomatic cover. Cuba provides intelligence expertise and methods of social control; China the architecture of surveillance; Iran and Turkey the laundering of illicit funds.

Across Latin America, criminal networks such as the Tren de Aragua thrive within this web – extensions of what Applebaum calls a metastasis of autocratic governments: a system that circulates wealth among elites, shields its members from accountability, and sustains itself through corruption and coercion.

Beyond money and repression, a network of mutual legitimation links Caracas with Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran. Each regime endorses the others’ elections, governance practices, and rhetoric about sovereignty and western hypocrisy, turning solidarity among autocrats into a geopolitical asset.

At its centre stands Venezuela’s TeleSUR, whose editorial line often echoes that of Russia’s RT, China’s CGTN, and Iran’s HispanTV, all of which argue for the construction of a “multipolar world” that resists western influence and sanctions. Together, these outlets recycle and translate one another’s content, creating a feedback loop in which disinformation is not merely imported but naturalised. The result is a trade in legitimacy: repression reframed as sovereignty and propaganda repackaged as pluralism.

What would, in the past, have been an ideological clash is, in fact, a collaboration. Regimes such as the one that runs Venezuela no longer compete for ideas; they cooperate to survive, laundering each other’s lies until repression looks like patriotism, and censorship looks like dignity. It is a bitter irony that those in the west who speak most confidently of their own moral clarity have often fallen for that system, unaware of just how they are being played.

During the years in which Hugo Chávez ran Venezuela, many progressive movements chose to see a revolution rather than an authoritarian drift. European parties such as Podemos in Spain and Die Linke in Germany, as well as figures within Britain’s Labour left around Jeremy Corbyn, praised the “Bolivarian process” as proof that socialism could defy US power. Any criticism of Chávez’s growing authoritarianism was waved away as imperialist propaganda, as though acknowledging repression meant betraying the anti-imperialist cause itself. Even as opposition leaders were jailed and the press silenced, solidarity rarely wavered. The result was a long moral hesitation: a reluctance to admit that a project once thought emancipatory had become coercive.

Under Maduro, this silence hardened into paralysis. In 2014, when protesters were killed and Leopoldo López, the opposition leader at the time, was imprisoned, governments across Latin America that were led by the left issued calls for “non-interference”. The Organization of American States was one of the few institutions to denounce the repression. By 2017, it was the Lima Group of mostly centrist democracies that recognised Juan Guaidó’s claim to be acting president, while Mexico, Bolivia, and Nicaragua stood by Maduro. In Europe, the pattern repeated: human-rights resolutions on Venezuela were backed largely by centrist blocs, while parts of the left abstained in the name of sovereignty.

Suggested Reading

Why Trump should never be given the Nobel peace prize

Independent organisations such as Foro Penal, Provea, and Transparencia Venezuela, which have documented thousands of political detentions, often found solidarity not from ideological allies but from whoever was willing to listen. Their strongest allies have been international legal bodies, centrist democracies, and global NGOs – not necessarily their original ideological kin. Even today, with almost 8 million Venezuelans displaced, only a few progressive leaders, notably Chile’s Gabriel Boric, have called the regime what it is. Others, including Lula da Silva of Brazil and Gustavo Petro of Colombia, urge dialogue without acknowledging the asymmetry that makes dialogue impossible.

Which means the genuine Venezuelan opposition has experienced a vacuum of support. That is why Machado has sought out alliances with Spain’s Vox-linked Carta de Madrid and with other European Conservatives. Her political inclinations take her towards the right, but her need to make these political friendships on the conservative fringe reveal what happens when solidarity fails. When democrats find no allies among those who should have stood beside them, they turn to whoever is willing to listen.

In the end, the moral high ground was not stolen by the right – it was relinquished by a left that chose distance over discomfort, purity over compassion and was unwilling to sit with any kind of compromise. And the cost of that failure is borne, as always, by Venezuelans themselves.

Machado and those who support her movement have risked their lives for this. The question is not whether foreigners approve of her politics, but whether they are willing to listen to what Venezuelans are saying through her. When we only accept Latin Americans who speak about themselves in ways that conform to certain comforting ideals, we are not listening – we are curating their voices, deciding who gets to speak and who must be spoken for.

Isabel Medem is a social innovator. She is the founder of Sanima, an award-winning social enterprise in Peru