In November 2022, Elon Musk sent an email to the staff at Twitter, which he had bought seven months earlier for $44bn. “We will need to be extremely hardcore,” he wrote. “This will mean working long hours at high intensity. Only exceptional performance will constitute a passing grade.” Anyone who declined was promised three months’ severance pay.

In buying Twitter, Musk turned himself into the network’s most visible user – and one of the most famous people in the world. In return for his billions, he acquired huge influence, a thousand fanboys and about as many demolitions in the liberal media. Whenever he made an apparently silly decision – scrambling the site’s verification mechanism, for example, so that a random prankster could claim to be a pharmaceutical company offering cheap insulin – onlookers were invited to read it through the prism of his genius. After all, this was the man behind PayPal, Tesla and SpaceX, as well as the less known Neuralink and Boring Company. He was Tony Stark in Iron Man – capricious, yes, but therefore an iconoclast, which is exactly what had made him successful. He had taken on the established, fossil-fuel-addicted auto industry and won. He had challenged the government’s grip on space travel, and triumphed. The qualities that allowed him to do this were his phenomenal work rate, his wide reading and perhaps even his self-confessed neurodivergence. Whatever he was, he wasn’t normal – the one thing that a genius cannot be.

Because of these qualities, Musk’s institutional and private backers calculated, he could remake the struggling social network, turning it from a niche product beloved by journalists and nerds into a profitable business with global reach. Twitter would now be the world’s “town square” and the home of unfettered free speech.

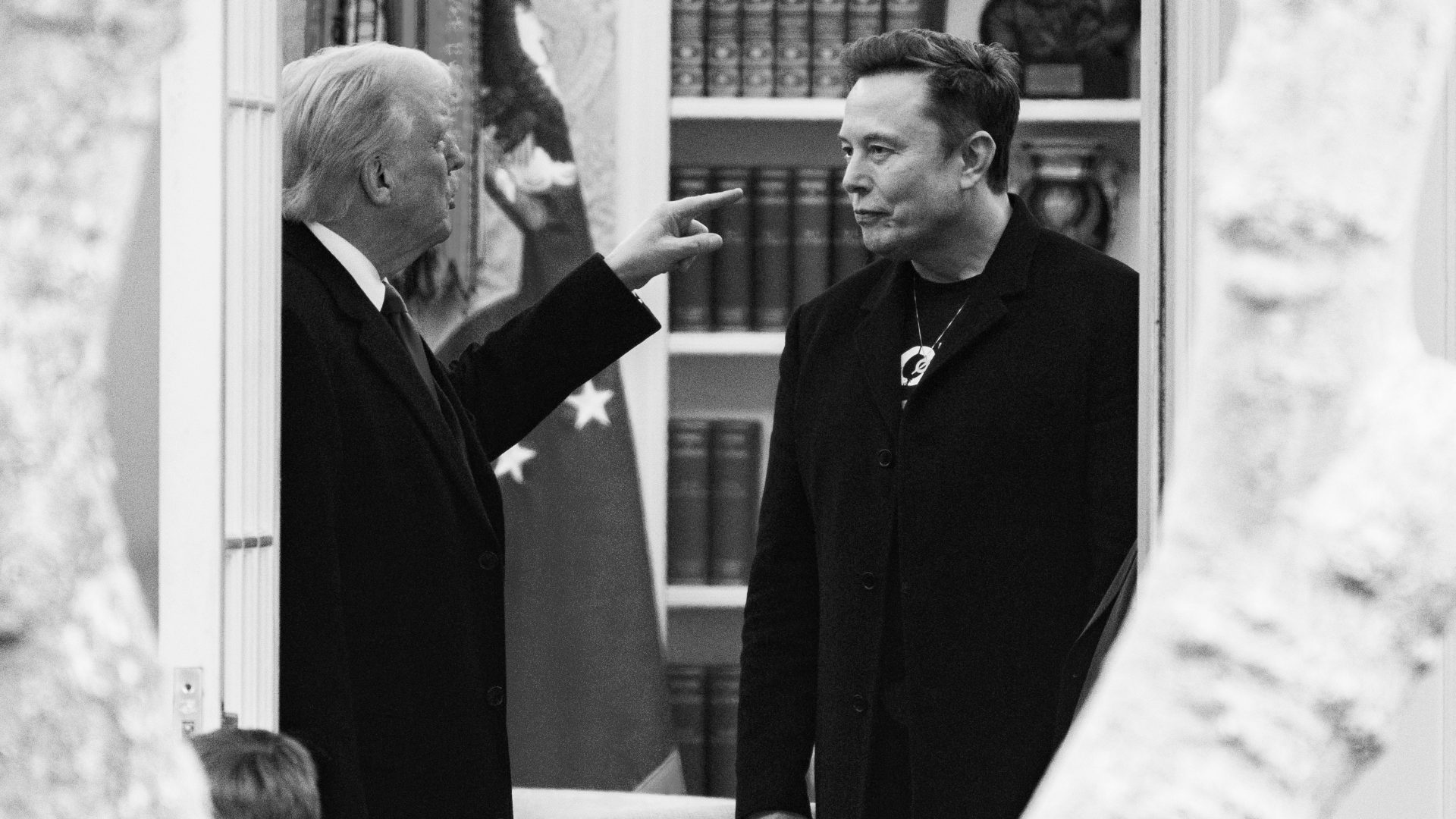

Of course, that didn’t happen. Since buying Twitter, Musk has rebranded the service as “X”, a name he has loved since his first days in California. He has also relaunched himself. His political committee donated more than $100m to the Republicans ahead of the 2024 US presidential election, and soon after Donald Trump’s win, he began to refer to himself as the “first buddy”. Throughout the campaign, he joked about a “department of governmental efficiency”, or DOGE, named after a decade-old internet meme about a cute dog. On stage at a rally in Madison Square Garden last year, he suggested cutting $2tn out of the US federal budget – a third of its value. The implication was that because he ran successful private companies, he could run a government better than a bunch of bureaucrats. He was duly appointed to Trump’s governing team as an adviser.

Suggested Reading

Watching my friend Elon Musk short-circuit

Musk’s political interventions have created a fierce giant-killing instinct. Who does this guy think he is? To me, his trajectory seems like a tragic example of someone being radicalised by social media – Musk made the drug dealer’s mistake of getting high on his own supply. Throughout 2024, he posted dozens of times a day on X – stealing memes, replying to conspiracy theorists and generally basking in attention. A whole gang of (mostly) men vied for his attention by saying the kind of things he liked to hear. The woke mind virus was killing America! Britain was a free-speech hellhole! The “mainstream media” was lying and biased, and only X could bring truth to the masses! At the same time, active user numbers fell, the “For You” feed filled up with flagrant racism and videos of random violence, and advertisers abandoned the platform. In January 2024, disclosure filings revealed that one of Musk’s backers, Fidelity Holdings, had marked down the value of their investment by 71%. The company, which he bought for $44bn, was now deemed to be worth just $10bn.

The schadenfreude was loud and unconfined. This alleged genius had taken a buzzy company, many liberals argued, and nosedived it straight into the ground. Even Musk took to saying that it was worth the financial loss to protect free speech – by which he meant the conservative and pro-Trump speech that he liked. The valuation of X has since improved – and in any case, Musk has now sold it to another of his businesses, xAI – but Musk’s reputation has not.

After years of being covered in the press like a visionary, the new DOGE-era Musk was now treated as an idiot. The harder thing to accept, however, is that the same person can be both. Musk is still the man who drove down the cost of space travel with reusable rockets, and who made buying an electric car seem cool rather than an act of penance. But he is also the man who keeps falling for badly photoshopped news headlines.

His detractors can’t accept this, and neither can he, because they both believe in the genius myth – that you’re either an all-round special person, or you’re not. How can the same person succeed so brilliantly at SpaceX and Tesla, and then go on to slash Twitter’s value by three-quarters? Simple: Musk is good at some things, and not at others. To understand that, we need to stop thinking of genius as a transferable skill. “At its core, SpaceX was a physics problem,” write Ryan Mac and Kate Conger. “Tesla was a manufacturing problem. But Twitter was a social and psychological problem.” Musk’s biographer, Walter Isaacson, had a similar take. “He really is a genius when it comes to material properties, when it comes to engineering,” he told Vanity Fair. But Musk was not a genius, Isaacson added, when it came to “human emotions”.

Suggested Reading

Helen Lewis: ‘Is Musk a genius? Look at his tweets’

The aura of genius that surrounds Musk has fed an equally strong impulse to debunk him. The most notorious example might be the 2022 sequel to the film Knives Out, which depicts a tech billionaire called Miles Bron. This Musk-like figure invites his friends to a private island to solve a murder. The big reveal is not the killer’s identity, but that Bron is an idiot who stole his big idea from his business partner – and the idea is terrible anyway, an alternative fuel that is too dangerous to be used. (In the years before the film’s release, several Teslas burst into flames when the batteries overheated.) Many Silicon Valley observers now slot Musk into the Miles Bron template. Musk has helped these people by not only giving them ammunition, but also loading the gun. He is addicted to publicity: there are wives – so many wives! – children – so many children! – and ever more absurd and inflammatory statements. So will he be remembered as a genius or an idiot? I do wonder if Musk has another act left in his career. At the time of writing, SpaceX is developing rockets for a manned Mars mission, which looks promising. The company has already succeeded in catching a reusable rocket – the size of a skyscraper – on a landing pad using metal “chopsticks”. Donald Trump will surely ease the regulatory burdens on SpaceX, which might either lead to a triumphant journey to the red planet, or a repeat of the Challenger disaster.

Think of it like this. When elections are over, everything the winning campaign did is often treated as inspired, and everything the losing campaign did as a costly mistake. This applies even when the margin of victory is a few thousand votes. The same is true of Musk’s genius – the judgment will be delivered in retrospect, only when we know whether his compulsive risk-taking has paid off. A Musk who dies on Mars, having conquered interplanetary travel, will be treated very differently to one who dies on the toilet of a ketamine overdose, halfway through commenting “LOL” on a picture of himself dressed as Pepe the Frog.

A more fair assessment of Musk is the one I gave at the start: that his work at Tesla and SpaceX shows flashes of genius, but he has succumbed to the idea that he is therefore a special person. That’s what I call the Genius Myth, and it’s poisonous. You can see it behind Musk’s prodigious sperm-distribution (genes like mine deserve to be preserved!), which does not appear to be accompanied by a similarly intensive interest in parenting the resulting children. Nature is enough; nurture is irrelevant. You can see it in how he treats his employees: anything less than cult-like devotion is unacceptable. And you can see it in his belief that you can run the state like a private business – specifically, one of his private businesses. But if X collapses tomorrow, the main effect will be that fewer racist memes get posted that day. If America’s social security payments don’t arrive, or if air traffic control fails at a major airport, or military secrets are left exposed on insecure servers… that’s very different. But someone who has succumbed to the genius myth believes that everything he does is equally brilliant.

So here’s my prescription: we should go back to the classical idea of genius as a visiting spirit. The Greeks and Romans thought that genius was something you had, not something you were. And we can all have moments of genius; Musk certainly has, for all that he is now best known as a poster of cringe memes. But let’s not confuse that with the poisonous notion of being a genius, someone whose every action springs from a superior intellect and understanding. In other words: appreciate the flashes of genius you see in the world – beautiful art, heartrending songs, scientific breakthroughs, technological innovation – without succumbing to the Genius Myth.

The Genius Myth by Helen Lewis will be published by Penguin Books in June 2025