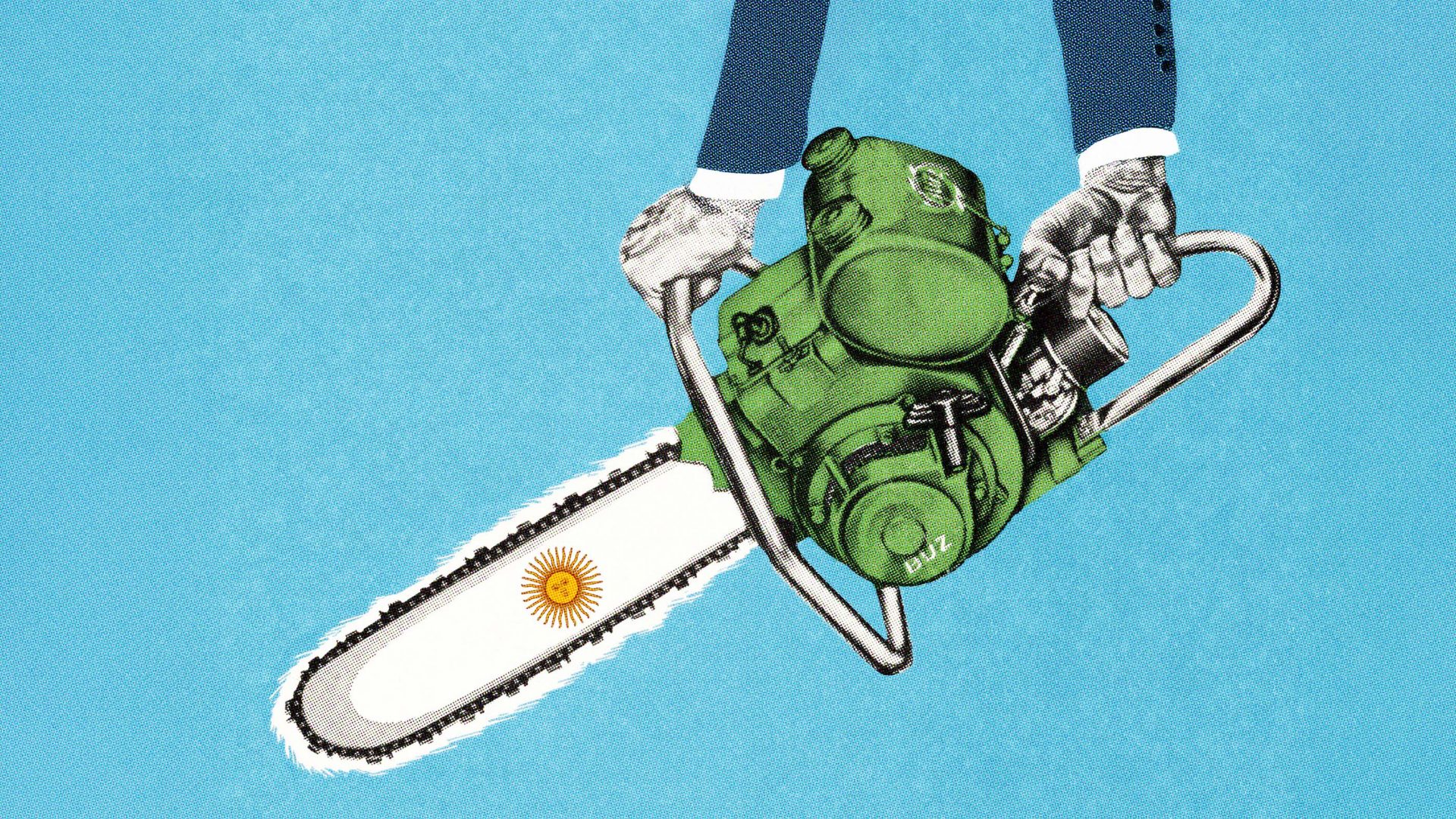

Javier Milei never sugarcoated what would happen. The former TV pundit and political outsider was elected as Argentina’s president on promises to take a chainsaw to the “bloated” state, “blow up” the central bank, and bury triple-digit inflation. After years of extreme economic volatility and rising poverty, Milei campaigned promising radical change, and in the November 2023 presidential runoff, he was rewarded with 56% of the vote. It was the highest percentage share since democracy returned to Argentina in 1983.

From the start he warned voters that it would be painful. In his inauguration speech, the self-described “anarcho-capitalist” told the crowd: “There is no money. There is no alternative to austerity and shock [measures]. It will have a negative impact on activity, employment, the number of poor and extreme poor.” The president – known by his critics as El Loco (the madman) – has been proved correct.

In his first 18 months, Milei has implemented a brutal austerity drive. He has slashed public spending and has cut tens of thousands of government jobs, public infrastructure projects and energy and transportation subsidies. Poverty rates have surged, and unemployment has continued to rise – it is now just under 8%.

And yet, despite all this hardship, Milei’s popularity has held firm. In June 2025, polling showed that 44% of Argentinians approved of his performance. Considering the extremity of his policies, it is a remarkable figure.

The reason? He has delivered on Argentina’s biggest problem: inflation. When he took office, inflation was running at a rate of 25.5% – per month. By May 2025, that monthly rate had dropped to 1.5% – its lowest level in more than five years.

That’s obviously good news for consumers, but the country still has an annual inflation rate of 39.4%, with prices rising 15.1% in the first half of the year. It’s pretty bad – yet better than the days when the price of groceries would change twice in a single day.

Which means the country is in a strange state of political suspension. People really don’t like Milei as a person. He is aggressive, rude and generally pretty odd. But there is an unmissable feeling here in Argentina that, despite it all, his policies seem to be working.

He has also managed to pull off a huge deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Argentina is known as a serial defaulter – in other words, it doesn’t pay its debts – and it has received more IMF bailouts over the years than any other nation.

Yet, in April, Milei somehow managed to squeeze an additional $20bn out of the IMF, even though the fund is wary of lending more money to Argentina.

Milei’s position as Donald Trump’s “favourite president” helped sway Washington’s support. That loan was enough to prop up Milei, which in turn allowed him to push ahead with his austerity drive.

All of which means that Milei appears to be outperforming all expectations, much to his opponents’ dismay, especially now in the run-up to October’s mid-term elections. But can he keep up the momentum?

For generations, Argentina has remained trapped between two political alternatives, both of them destructive: populist left governments have printed too many pesos and simply given them to the poor; and the populist right leaders have handed out cheap dollars to the elite. Both of these alternatives have traditionally ended in economic disaster. Milei, who paints himself as a political outsider with radically different ideas, is essentially taking the latter course.

Suggested Reading

How Javier Milei brought hatred to Argentina

His gamble is that he can kill off inflation by boosting the value of the currency. The worry is that this strategy has been tried – and has failed – before: in the 1970s, 1990s, and under the presidency of Mauricio Macri in 2015-19. While Milei’s attempt seems to be going well, the overvalued currency still poses systemic risks.

Marcelo Garcia of geopolitical risk firm Horizon Engage pointed out the flimsiness of the situation. “In the first quarter of this year, the country spent more dollars in foreign tourism – this is Argentines sipping caipirinhas in Rio de Janeiro – than it made from Vaca Muerta oil exports,” he said. “That’s a big problem. Milei is cruising [towards a] wall of overindebtedness and eventual default. Unless he corrects, he will crash into a crisis.”

A stronger currency means you can buy more from abroad, and that surge in imports means your domestic small businesses and manufacturers face new competition and begin to struggle. The textile industry, for example, is experiencing its worst period in the last 25 years, according to Marco Meloni, president of the textile firm Italcolore SA. “Activity is at 40%, less than half of what it was in 2023.”

It’s also worth noting that the IMF deal didn’t please everyone. Argentina had racked up 22 IMF loans since 1958, and already owed the IMF more than $40bn. Critics complain that IMF funds have been used to repay the lender itself, and blame the IMF for the country’s economic implosion and the debt default in 2001. Why, they asked, was the country taking on even more debt?

Politically that’s a very, very awkward question. But perhaps the biggest problem of all is that the current economic programme is not what Milei promised. He promised to “dollarise” the economy, to shut down the Central Bank and cut ties with China. None of these things have happened.

Meanwhile, inequality is deepening – he didn’t promise that either. While poverty was already high before Milei took power, in his first year, public spending was slashed, wages depressed, rations to food banks stopped, and free medicines cut back. The healthcare budget has fallen by 48%, with millions of dollars of free cancer drugs halted, while the education sector has also been gutted, and inflation adjustments for pensions cut.

“There’s a very high social cost that we are paying,” said Luna Miguens, of Argentina’s pro-democracy thinktank, the Center for Legal and Social Studies. “It’s been really brutal, and it’s not a neutral adjustment. It is affecting vulnerable people with low incomes and especially retired people.”

An estimated 800,000 people no longer have their medicines covered by the public system, Miguens said. There is certainly a travel and shopping boom, but it is only enjoyed by a privileged minority. The less well-off are already cutting back on spending. The economist Federico Pastrana calculated that real wages have fallen every month since January, amounting to a total decline so far this year of 5.5%.

And then there’s the ideological “anti-wokery” line. Milei has been accused of using Trumpian, authoritarian tactics to wield his power, suppressing the right to protest, and attacking press freedoms. He has drastically defunded gender-based violence programmes, halted the delivery of abortion medication, and sought to remove environmental protections.

Milei seems to think that Argentinians voted for him so he could completely overhaul the country, turning it into, as Garcia says, “a country that has less government, fewer unions, less solidarity, less federalism. Pretty much like Thatcher in Britain. And I believe he’s wrong – Argentines didn’t vote him in for that.”

Milei is currently expected to do well at the mid-term elections – like his fellow populist president up north in the US, he is still adept at sucking up all of the media’s attention, denying the oxygen of publicity to his opponents. There’s no doubt he has delivered economic improvements. But he has also brought a new callousness into modern Argentinian politics.

Milei doesn’t care about the old, the poor, the disabled, the unwell – or at least, he embodies a style of politics that has nothing to offer these people. It is not clear that Argentinians like that approach. In the long run, there is a strong chance that, for Milei, simply fixing inflation will not be enough.

Harriet Barber is a freelance journalist based in South America