The Conservatives are entering panic mode. You can see it in Kemi Badenoch’s eyes at Prime Minister’s Questions, flashing terror and boredom in rapid rotation. In her time as party leader she’s made little impression on the party’s devastating polling. Insiders worry they’re edging into wipeout territory but feel paralysed to do anything.

Badenoch has many problems as leader, but the greatest might be this: she appears to have no idea where her remaining core vote is, or how to appeal to it. While voting patterns have become increasingly unpredictable, one demographic is unmoving: women over the age of 55 are still supporting the Tories.

This pattern is true across nations, with centre right parties holding on to older women, but this understanding appears to have been drowned out by the well publicised broader trend of female voters leaning left while men are turning more strongly to the right. Here in the UK, the clamour over the surge in popularity for Nigel Farage’s Reform has also distracted from the desires of older women – but they are simply not being tempted away by populism.

Rosie Shorrocks, senior lecturer in politics at the University of Manchester and an expert in demographic polling trends, says older women are a “forgotten base” for the Conservatives. “They don’t take it for granted; they don’t even realise that this is what their base is,” she says. “I don’t see any evidence that they are aware that this is a group that is strongly voting for them and has done through periods of high levels of political change from 2010 onwards.”

According to Shorrocks, part of the reason that older women are sticking with their allegiances is due to their past habitual voting patterns: they have always voted Conservative (or have done for at least two decades) so they now feel a personal identification with the party.

Although they are being ignored now, that hasn’t always been the case. “The Conservatives, prior to the last few years, did put a lot of effort into retaining that group. Especially when you look at the 2010 and 2015 elections, they were very successfully talking about protecting pensions and becoming more convincing on the NHS. What happened then is that the political debate moved away from those things. It moved onto things, such as immigration, that older women cared less about – but that also meant they were less likely to attract their vote.”

In last year’s general election, 29 per cent of women aged between 50 and 64, and 42 per cent of women aged 65 or over, voted Tory. Shorrocks expects these polling rates to hold up despite the damaging local election results in early May. “We can’t just decide all these people have deserted the Tories,” she says. Although recent analysis seems to suggest Gen X women (born between 1965 and 1980) are being successfully courted by Reform, if you look at votes of those over 55 that trend is not replicated.

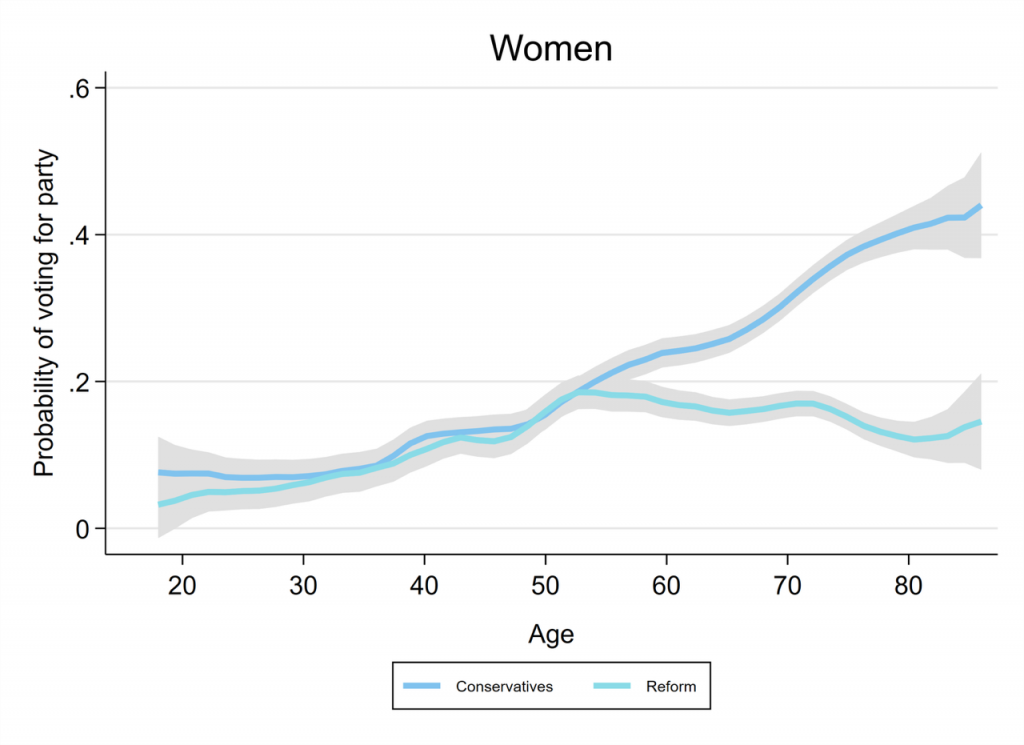

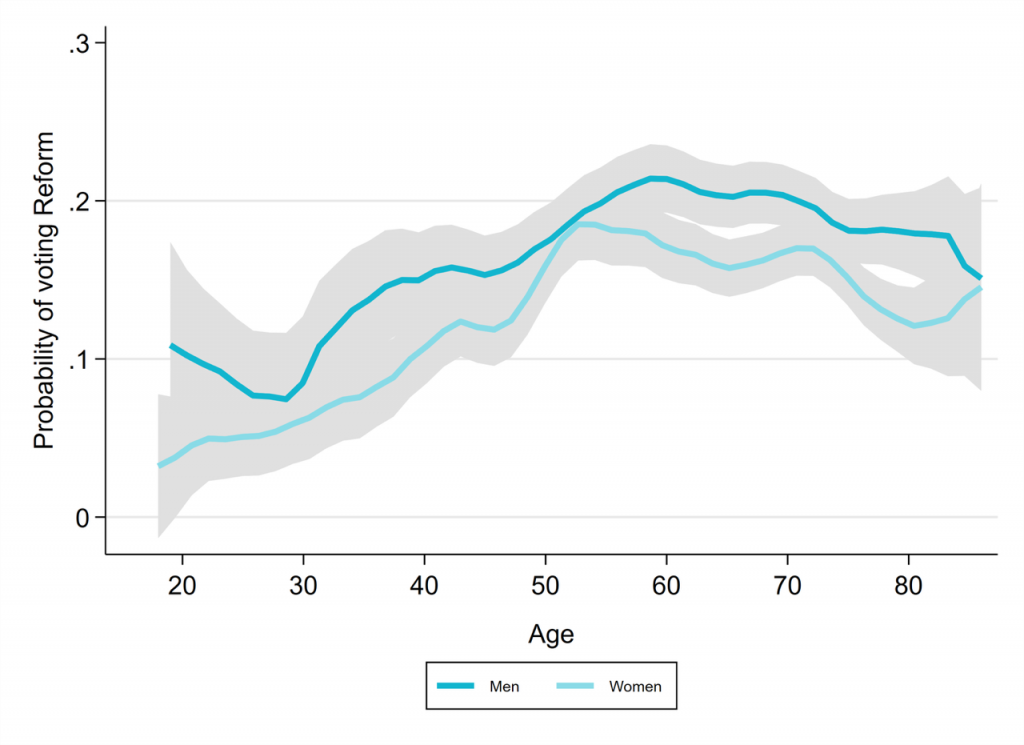

Older men, however, are less likely to stick with the Conservatives. Data from the British Election Study tracking the likelihood of moving from a former party to Reform shows a significant gap opening up between men and women in their propensity to support Farage’s insurgent party. Although the probability of voting Conservative or Reform is equally matched between the sexes up until age 50, at this point there is a divergence right up until the age of 80, when it equalises again. After the age of 50 women are much more likely to vote Conservative than Reform, and that trend continues to widen until the end of life.

There are a number of reasons for this gap. Global studies show that this pattern is repeated across nations (including Europe and Canada) due to older women’s greater likelihood to have a faith and vote in accordance with religious values. Here at home, the lack of interest from Reform in issues that women say matter to them – the NHS, social care and pensions – and the increasing radicalism of the political language used both by Farage’s party and the modern Conservatives mean that women are simply unmoving.

Mid-cycle fence-sitting, and election day turnout rates, also play a part. Research shows that women are more likely to be undecided in their vote choice, but as likely to turn out to vote. Turnout is higher among older people in general, with a very steep age gradient noted in recent elections, and it is also known that Conservatives are older in general, with an average age of over 70.

“I put all these things together and come up with the theory that Conservative women are disproportionately undecided, disproportionately less likely to back Reform over the Conservatives, but as likely to vote, so I think they may have swung behind the Tories, and might have been less responsive to pollsters,” says Jane Green, director of the Nuffield Political Research Centre at the University of Oxford.

So what can the Tories do to consolidate and build on this support? The first is to change their rhetoric. Issues such as the Supreme Court verdict over trans women’s rights, which Badenoch used as an opportunity to attack the prime minister aggressively, are a red herring. Older women may hold more gender critical views, but they are more traditional in their values which means they are also not basing their voting decisions on those issues. “The more time you spend on those things and sounding very passionate about it, the less time you’re spending talking about the things that really matter to them,” says Shorrocks.

The NHS is the obvious policy focus for Badenoch if she wants to consolidate her base. Health is both a practical and emotional concern for older women. A third of older women say their health has worsened in the past year, compared to only a quarter of men, according to Age UK research published in March. Older women also feel less confident than their male counterparts that their health will improve in future.

Social care is also an important policy area for older women. They may need it themselves, they may still be caring for very elderly parents and relatives too, and they may wish to prevent such a burden being passed onto their own children. As Cardiff University politics lecturer Emmy Ekhlund puts it: “Women are on the receiving end of the policy choices of Reform, which makes it not a desirable choice.” The political message “Burn it all down” is not one that attracts older women. Once it’s been destroyed, who will rebuild it? Women know it falls to them.

With Starmer chasing down Reform over immigration, and changing his political language in the process, now is the perfect time for Badenoch to capitalise and build on the Tory reputation among older women as a moderate voice on the right. She’ll need to execute a handbrake turn to take advantage of it.