The slogans on Sarajevo’s billboards and big screens urged passers-by to “Remember Srebrenica”. Very large crowds attended the 30th anniversary commemoration of the genocide, which took more than 8,000 lives in and around this tiny town in eastern Bosnia. But the people who live there feel they are largely forgotten for the rest of the year.

The Srebrenica Memorial Centre welcomes more visitors on July 11 than on the other 364 days of the year put together. The crowds arrive by car and bus, but there are also organised groups of motorbikes, quad bikes and plain old push bikes, each with their own police escort. Nearly 7,000 arrive by foot, after taking part in the annual, three-day peace march.

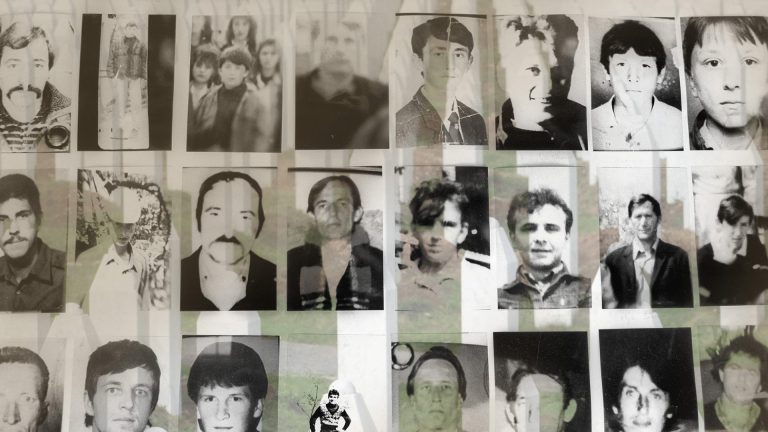

The Srebrenica-Potocari Cemetery – now with almost 7,000 white obelisk gravestones – is on one side of the road. On the other side, the grey, utilitarian blocks which once served as a base for UN peacekeepers now form the Srebrenica Memorial Centre. Neither are equipped for the summer festival-sized crowd which descends every July.

On the day of the commemoration, volunteers from Islamic Relief handed out water bottles to pilgrims wilting in Bosnia’s fierce summer heat. A kiosk opposite the cemetery gates was disconcertingly topped with a sign proclaiming “SOUVENIRS” and was doing a roaring trade in espresso from a domestic bean-to-cup machine for a euro a shot.

I ducked into the administration building next to the museum where dignitaries ranging from European Council President Antonio Costa to the Duchess of Edinburgh were delivering the usual promises that the world should neither forget nor repeat the horror of Srebrenica. And, as luck would have it, I bumped into an old acquaintance.

Hasan Hasanovic remembered our conversation from 10 years earlier, under the shade of the trees near Srebrenica’s mosque – as did I, vividly. He had told me how he, his father, Aziz, and twin brother, Husein, had attempted to escape from the town in July 1995. Along with thousands of others, they made their way through the forests, under fire from Bosnian-Serb forces. In the chaos, Hasan became separated from his brother and father. He never saw them again.

Suggested Reading

Bosnia’s enduring pain

Hasan has offered his testimony many times over the past 30 years. But now, as head of the Oral History project at the Memorial Centre, he focuses on gathering the stories of other survivors. He has interviewed more than 700 people, adding their accounts to the centre’s ever-growing archive.

Over coffee in his office, Hasan was also keen to talk about the present. He told me that Srebrenica was “only on the radar once a year”.

“It feels like this is the end of the world,” he said. “Either you’re stuck here, or you move and never come back.”

“So much has been done in terms of memorialising the genocide – but when you see how the town, the municipality is recovering, it’s not going well. I had hoped that here, the world would make more efforts to show that life is possible after genocide, that reconciliation is possible. If we don’t show that life is possible here, where life was basically destroyed, then I am very worried for the future.”

Srebrenica, with its quiet streets, feels like a place in decline. Fewer than 3,000 people now live in the town itself – and that number shrinks further as young people leave to seek a better life elsewhere.

Still in her 20s, Mirela Osmanovic is one of those who has stayed – but as I spoke to her at the Memorial Centre, she lamented the “specific” atmosphere which meant her neighbours included “potential perpetrators, genocide deniers and those who glorify war criminals”.

“I am the proof that the reconciliation process hasn’t even started,” she told me. “If I feel the consequences of something that began and ended before I was born, something is wrong.”

Indeed, Bosnia and Herzegovina remains in a state of frozen conflict. The Dayton Peace Agreement brought the fighting to an end in 1995. But it also divided the country on ethnic grounds, splitting it into two so-called “entities” which hold more power than the weak state-level government. Ever since, ethno-nationalist politicians have delighted in the opportunity to divide, rule and profit – with ordinary people paying the price.

Guy De Launey is an award-winning Balkans correspondent