When 39-year-old Abdul Qadeer Khan walked out of his office in June 1975, no one thought much about it. It was a lovely summer’s evening in the Netherlands, and he gave a friendly wave to the security guard as he mounted his bicycle for the ride home.

Little did his employers know that he had just committed one of the most consequential acts of espionage in world history, one that has taken on a chilling significance in the light of Israel’s attack on Iran, and India and Pakistan’s recent exchange of fire across the border. The offices that Khan left behind belonged to Urenco, a British-Dutch-German multibillion-dollar operation delivering enriched uranium and plutonium to 130 of the world’s 410 nuclear power plants.

In the briefcase strapped to his bike on that day were secret papers that would provide Khan’s homeland of Pakistan with the nuclear bomb. Those plans would also provide Iran with the nuclear enrichment programme that Israel has now set out to destroy. There is a direct line between the contents of that briefcase and the Israeli strikes on Tehran.

The information he stole would set him up in business as the ultimate “merchant of death”. Khan had taken his first steps to becoming the “father” of the Iranian, Pakistani, North Korean and Libyan nuclear weapons programmes.

Khan was born in pre-partition India into a devout Muslim family. When he turned 16, he followed his older siblings across the border into Pakistan where he studied engineering, first at the University of Karachi, from there moving as a scholarship student to Germany and then on to the Netherlands. He earned his doctorate from Leuven University, which led to the job at Urenco.

At Urenco, Khan was given the task of improving centrifuges, machines that spin at high speeds to separate different isotopes of uranium from one another. In the nuclear industry, centrifuges are essential to the process of enriching nuclear fuel.

Most deposits of uranium are made up of uranium-238, a stable form of the element that is not suitable for making nuclear fuel. But contained within these deposits are trace amounts of uranium-235, a highly fissile isotope that can be used in both nuclear reactors and weapons.

Uranium hexafluoride gas is fed into the chain of centrifuges, which spin at high speed. The U235 will concentrate in certain parts of the centrifuge, and this more concentrated gas is then passed into the next centrifuge where the process is repeated, and as the gas moves down the cascade, the concentration of U235 increases. This is enrichment. Uranium used in nuclear power plants is typically enriched to a level of around 3-5% U235. Weapons-grade uranium is enriched to over 90%.

On May 18, 1974, India exploded its first nuclear device, and Khan immediately went to the Pakistan embassy in The Hague and offered his services. He would help Pakistan to develop its own bomb. He was told to wait. At the end of 1975, Khan was refused a promotion at Urenco and he immediately wrote to the Pakistani prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, offering his services. Bhutto told him to come home.

It is now known that western intelligence was aware of Khan’s thefts before he left for Pakistan. One of his colleagues, Frits Veerman, noticed secret documents in Khan’s home and alerted the Urenco management. Veerman’s whistle-blowing activities got back to the Dutch Security Service (BVD), and they shared this information with the CIA. But according to the former Dutch prime minister, Ruud Lubbers, the Dutch were told by Washington: “Do not arrest the man; just let him go ahead… we will have him followed and gain more information.”

In 1983, the Dutch government tried Khan in absentia for nuclear espionage. He was convicted. But even then, higher priorities intervened. The conviction was overturned on a technicality in 1985, and Lubbers later revealed that in 1986 the Netherlands again refrained from further action at the CIA’s request. It was the height of the cold war. The Soviets were in Afghanistan, and Pakistan was an important ally. Washington seemed more interested in quietly tracking Khan than in stopping him outright. But letting Khan walk was a grave mistake. Over the next three decades, AQ Khan became responsible for a global wave of nuclear proliferation.

Suggested Reading

Israel strikes as the sheriff leaves town

Back in Pakistan, he joined the nuclear weapons programme headed by Munir Ahmad Khan. The undertaking, codenamed Project 206, had been in operation since January 1972 and aimed to develop a nuclear weapon using plutonium. At a meeting between Bhutto, Abdul Qadeer Khan and Munir Ahmad Khan, AQ Khan persuaded the prime minister that the better route lay with enriching uranium using the centrifuge technology he had stolen in the Netherlands.

Throughout the 1980s, Washington supplied billions in aid to Islamabad, which was transferred across the border into Afghanistan to support the war against the Soviets. This continued even as evidence mounted that Pakistan was secretly building a nuclear bomb. Cold war imperatives were so important that successive administrations were not even deterred by the 1985 Pressler Amendment, which banned most aid to Pakistan unless the president certified annually that “Pakistan does not possess a nuclear device…”

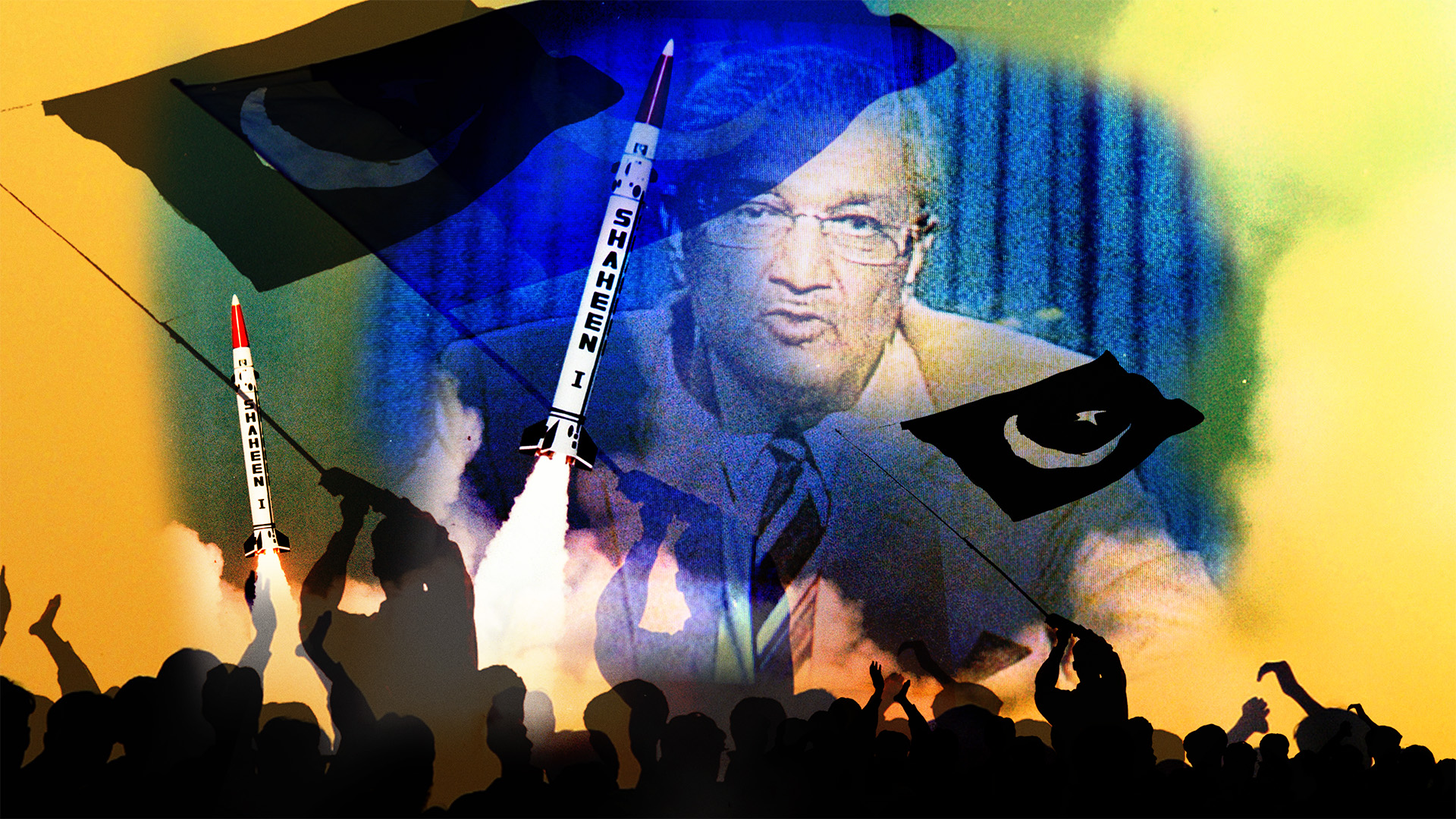

US aid remained in place until the Soviets left Afghanistan. Then in 1990, president George HW Bush refused to certify aid under the Pressler Amendment. (It was not restored until the attacks of September 11, 2001 when Pakistan again became a major ally and base of operations for Nato actions in Afghanistan.) In the meantime, Khan and his team worked away with their centrifuges, protected by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Agency. On May 28, 1998, Pakistan exploded its first nuclear device high in the hills of Balochistan.

But Khan had wider ambitions. Even by the late 1980s – well before Pakistan’s first nuclear tests – he was investigating the sale of nuclear weapons technology to other nations. Now beginning to grasp the commercial potential of the information he possessed, Khan established an elaborate network of shell companies and middlemen in over 20 countries.

Khan’s first customer was Iran. In 1987, he offered Tehran the centrifuge designs he had stolen in Europe along with a starter kit of components, all for $3m. This deal jump-started what would become Iran’s nuclear programme. Iran built its first enrichment machines based on Khan’s design, and later received drawings for a more advanced form of centrifuge.

Western intelligence gradually caught on. By 1989 the CIA had learned of Khan’s 1987 sale to Iran. However, US analysts at the time believed this was a one-off or that the episode, though worrying, had led nowhere, especially after the 1990s brought Iran new nuclear contacts with Russia. In reality, according to later International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) investigations, Khan remained Iran’s primary nuclear supplier throughout the 1990s.

At around the same time, Khan cultivated another client: North Korea. Starting in the late 1980s and accelerating in the 90s, Pakistan and North Korea entered into a secret barter arrangement, often described as “missiles for nukes”. North Korea had ballistic missile technology that Pakistan’s military desired, and Khan had enrichment expertise that Pyongyang needed.

Western intelligence agencies strongly suspected the Khan-North Korea connection, but struggled to prove it. US satellites tracked unusual flights and Pakistan-North Korea military contacts, and by the late 1990s and early 2000s, fragments of evidence including intercepted shipments and statements from defectors pointed to a clandestine enrichment programme in North Korea. Still, Pakistan’s government vehemently denied any nuclear cooperation. It was only later that the proof emerged.

Khan was no longer the patriotic head of Pakistan’s nuclear programme, but had become the chief executive of a profit-driven international nuclear proliferation network. As well as Iran and North Korea, Khan tried and failed to sell his bomb factories to Syria and Iraq. Then he struck what he thought was gold. In 1997, Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader, agreed to pay Khan $100m for a uranium enrichment plant. It was in effect a bomb factory.

This massive project entailed thousands of centrifuges, designs for a nuclear warhead and technical support. To fulfill Libya’s order, Khan had to broaden his network beyond its original scope. More people meant more risk, and the Libya deal soon began attracting attention.

Intelligence agencies from multiple countries were on Khan’s tail as his fingerprints turned up on one proliferation case after another. Starting in around 2000, the CIA and MI6 mounted an intensive operation to penetrate Khan’s network from within. British and American intelligence officers, working closely together, recruited informants and encouraged some of Khan’s trusted associates to inform on him. They monitored Khan’s international travels and placed his communications under surveillance, secretly listening to phone calls and following the money flows.

“We were inside his residence, inside his facilities, inside his rooms,” one CIA official later remarked, describing how deeply the agencies managed to infiltrate Khan’s circle. Key figures in the network who had been co-opted by western intelligence included a British member of Khan’s supply team, an engineer named Peter Griffin, who reportedly cooperated with investigators. A family of Swiss technicians, Friedrich Tinner and his sons, began assisting the CIA, providing critical information on Khan’s shipments.

By 2002, these efforts were bearing fruit. Western intelligence had mapped out much of Khan’s network – from manufacturing sites to front companies and shipping routes. Realising that an intelligence net was tightening around them, Khan’s operatives grew nervous. In mid-2002, they began shredding documents and deleting emails in large volumes to cover their tracks. Despite this destruction of evidence, enough information had been gathered by the CIA, MI6, and their partners to move in for the kill. The climax came in October 2003, when a pivotal sting operation was executed on the high seas.

In October 2003, a German-flagged freighter called the BBC China was intercepted en route to Libya. Acting on intelligence tips, agents from the CIA and MI6 – with help from German and Italian authorities – seized the ship and discovered a cargo of sophisticated centrifuge parts packed in containers for delivery to Tripoli. Khan had been caught red-handed.

Gaddafi now faced the stark revelation that his nuclear secret was out. Within weeks, Libya contacted the US and Britain to negotiate the surrender of its weapons of mass destruction, and in a clandestine meeting in early December 2003, Libyan officials hosted CIA and MI6 officers and revealed everything. They handed over detailed documentation of their dealings with Khan.

The unravelling of Libya’s nuclear programme gave Washington and London the leverage they needed to confront Pakistan. Faced with incontrovertible proof of Khan’s operations, president Pervez Musharraf was forced to arrest him. He made a full confession on Pakistani television. The next day he was pardoned, but remained under house arrest.

For many in Pakistan, Abdul Qadeer Khan remained a national hero. He died on October 10, 2021, a victim of the Covid pandemic. He was given a state funeral.

Khan’s legacy is a network of nuclear-armed states that now stretches from the far east of Asia, across the subcontinent and into the Gulf and to the smoking buildings in Tehran. It is because of AQ Khan that Israel launched its strikes on Iran, taking the region – and the world – towards war. If Iran now races for the bomb, their ability to do so will derive directly from the plans he stole. It is why, when India and Pakistan begin launching missiles at one another, the world confronts the real possibility of a slide into nuclear war.

That is all down to one man, and his decision to get on his bike one day with a case of secret documents, to leave work and never return. Once he had made that decision, there was no going back.

Greg Treverton was chair of the National Intelligence Council in the Obama administration. Tom Arms is the author of The Encyclopaedia of the Cold War and writes the weekly world affairs blog Observations of an Expat on Substack.com