“You’re moving where?”

“Colombia, mum,” I repeat.

“Ain’t that dangerous?” she asks.

It’s a fair question. In the early 1990s, Medellín was considered the world’s most violent city. Mum makes it clear she wishes I’d stay in safer Buenos Aires. But I want to escape the Argentinian winter.

“Medellín isn’t as violent as it once was. The whole country isn’t,” I say, trying to reassure her.

“Medellín?!” she asks. Isn’t that where Pablo Escobar…”

It is, I tell her, but he’s a long time dead.

Escobar’s brand of brutal, murderous narco cartel violence, coupled with that of armed guerilla groups, while not dead, has reduced enough for the city to welcome tourists over the past decade or so.

It’s been a concerted effort by Colombia and Medellín’s political class, to completely rebrand the country and its famous city. They achieved it by signing a peace deal with the leading Marxist rebel group, FARC, in 2016, creating a more peaceful environment into which remote workers like me could enter without giving our mothers heart attacks.

It’s surprising this is even possible. The violence, gangland killings and political assassinations all seem so recent. The rapid transition has been alliteratively termed the “Medellín miracle”.

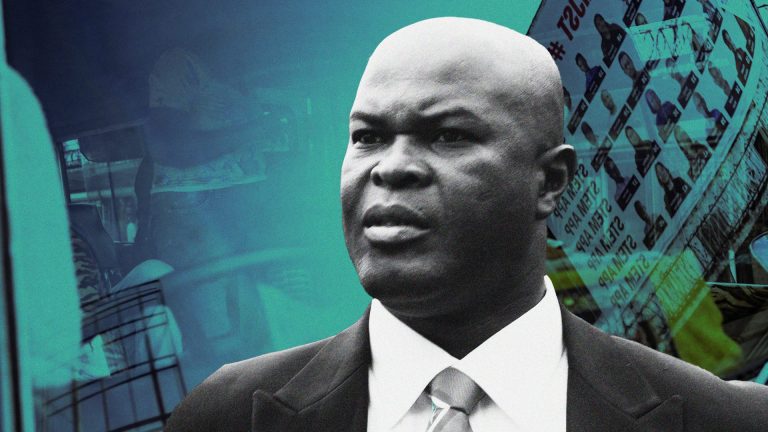

And then it happened. An assassination attempt on right wing senator and potential candidate in next year’s presidential election, Miguel Uribe Turbay. He was shot twice in the head while giving a speech in the capital, Bogotá, the bloody details of which were captured on smartphone. The suspect is just 15. He has pleaded not guilty.

There’s nervousness that, should he die, paramilitary groups could re-arm, and the situation here could again start to slide out of control. Turbay saw that in his lifetime: his mother, Diana Turbay – one of the country’s best-known journalists – was killed in 1991 in a botched rescue attempt after she’d been kidnapped by Escobar’s Medellín cartel. She was 38. Turbay (and his mother) are very much from Colombia’s political class. His grandfather was the country’s president from 1978 to 1982, during a period of intense guerrilla violence. Now, the grandson remains in critical condition in hospital following brain surgery.

Suggested Reading

Bigi Bravo is set for 20 years in power

Juan Esteban Agudelo, 35, lives in Bogotá. “As a Colombian who grew up in the late 80s,” he said, “the assassination attempt on a presidential candidate, along with some other violent guerrilla acts, do seem like a flashback to that period.”

The other violent guerilla acts refer to a rise in kidnappings, displacement and violence, mostly in the countryside and smaller cities. Uribe has argued for a hardline approach to the country’s armed groups, in contrast to Colombia’s leftist president, Gustavo Petro, who has promised to strike peace deals with them. Opponents are getting impatient.

“Even though it’s not equally comparable in magnitude,” Agudelo said. “It does seem like we’re experiencing a setback in national security.”

Unlike Turbay’s mother, journalists like me can today write without fear. When Turbay was four, people like her were picked out by Escobar’s Medellín cartel because he was targeting people “from the so-called high society,” to protest the extradition of Colombians to the United States.

Speaking to me from Medellín where she grew up, Pollyanna Zapata, 39, said: “Violence in Colombia has decreased rather than ceased. We were once one of the most violent cities but now there’s tourism (the good and the bad that brings). The economy is moving and people have found ways to confront the past with new strategies.”

She’s dubious it’ll last. “Before next year’s presidential elections, I believe attacks and chaos will once again reign on our streets. That’s the only way the right can regain what it lost with the change of government.”

Violence was once a common political tool in Colombia – between 1986 and 1990, five presidential candidates were murdered. The country’s last high-profile political assassinations were in 1995.

Meanwhile, in Poblado, where I’m living, the Medellín miracle continues. It’s digital nomad central here. People seem blissfully oblivious as they stare into their Apple Macs and sip flat whites. I wonder if they realise the real miracle is democracy itself – fragile in 2025 in countries where we thought it was a permanent resident.

Gary Nunn is a freelance journalist.