Shortly before he died at the age of 24, James Dean said: “If a man can bridge the gap between life and death. I mean, if he can live on after he has died, then maybe he was a great man. To me the only success, the only greatness, is immortality.” By his own reckoning, in the 70 years since his death, James Dean has become a great man.

In a tiny town called Cholame in the foothills of the California desert, there really is nothing at all. A closed-down cafe, a disused road that has been bypassed with a new highway, crinkly rolling hills, brittle-dry grass, and an unrelenting sun. Behind the cafe in a small grassy patch are the brick foundations of a garage. It was knocked down long ago.

It was in this garage, 70 years ago, where the crumpled remains of a silver Porsche 550 Spyder and a Ford Custom were winched and towed from the site of a fatal crash that had occurred just down the road. In a layby in front of the cafe is an oddly disjointed modern sculpture, silver and angular. It curves around a tree bearing the inscription “James Dean 1931 Feb 8 – 1955 Sept 30 pm5.59.” The figure 8 is missing, just a shadowy outline where it used to be.

The sculpture, commissioned and erected by a Japanese Dean fan called Seita Ohnishi, was once mirror-like. The purpose was to reflect an intersection about half a mile up the road, the exact place where James Dean died in a crash.

This intersection where Route 46 meets Route 41 even today is known as “Blood Alley” because of the number of accidents that occur there. Ominously, the San Andreas fault runs right beneath the road, and the dry-bed creek shows signs of the shifting plates with alarming surface ruptures.

As Route 46 whizzes from Los Angeles to the coast, at Cholame, Route 41 veers off sharply to Fresno. To make the turn, you have to cross into the oncoming traffic. This is what a young student, Donald Turnupseed, attempted to do on the evening of September 30, 1955.

The unrelenting sun was finally falling in the sky and the glassy updraught from the road made visibility difficult. As he made the turn on to Route 41, he failed to see the small silver Porsche driven by James Dean speeding down the hill towards the junction. The colour of the car, the time of day, the speed of both drivers, the road layout, all contributed to the collision.

Dean, although young, was becoming an experienced racing-car driver – that is why he was on the road from West Hollywood to a race in Salinas the next day. He realised the Ford Custom had not seen him and pulled a manoeuvre to avoid the car. Turnupseed, less experienced, instead of stopping, continued driving into the junction and Dean was not able to prevent the collision. He died almost instantly from a broken neck and internal injuries.

The actual site of the crash has become a pilgrimage site for James Dean fans. And what you find there is both moving and uplifting. It is neither ghoulish nor depressing, but rather an affectionate celebration and a point of remembrance.

Last summer, during a trip to LA, I decided that I wanted to do the full pilgrimage, driving from West Hollywood to the dry, scorched intersection at Cholame, following Dean on his final drive. This is no small feat.

For a start, it is very hot and is quite a long way — a good eight-hour round trip. Second, I don’t drive. Luckily, I found a partner in crime, which not only meant that I could be in charge of routes and stopping-off points, like secular stations of the cross, but it also gave me plenty of time to dwell on what occurs during such a pilgrimage and why they are carried out.

First of all, the car is important. James Dean loved cars and he loved racing. He would noisily whizz around studio lots on his motorbike or in vehicles, resulting in studio boss Jack Warner calling him the “little bastard”. Dean had this name written on the trunk of his new Porsche Spyder, words that would poignantly survive the crash.

We hired a bright-red Mustang and left West Hollywood early one June morning, roof down, ready for an exciting drive to Cholame. Less than half a mile from the apartment, we ground to a halt in Laurel Canyon traffic. This was the road where Dean would race up and down, usually pulling out on to Sunset Boulevard without looking.

Immediately I realised that the whole trip was going to take place in some sort of temporal parallel reality. Me, here and now; Dean, there and then. But then maybe that is the nature of all pilgrimages; you experience the journey in real time alongside daydreams of what was. For it to work you have to imagine a time you could never experience.

The first stop is in Sherman Oaks, where Dean filled up his Porsche at the Mobil gas station on Ventura Boulevard. The site is now a Whole Foods store, though there is a beautiful Cadillac building across the street, still intact, which features in Sanford Roth’s photographs of Dean taken on his final day.

I stand as close as I can to where the petrol pumps would have been, but of course they are not there and have not been for many years. Sometimes on pilgrimages of this nature even your imagination fails faced with modern, concrete reality.

From this point, though, the drive grows more exciting as Los Angeles becomes a shimmering mirage in the rear-view mirror and the highway starts to cut between hilly passes. The landscape changes quite suddenly from urban to rural. It becomes drier and the hills become not quite moonscape but very wrinkled. The view cinematically opens up, with vast horizons and a slight, otherworldly light.

A couple of hours pass in these hypnotic mountains, where my thoughts drift to the daydreamy nature of such pilgrimages. There is something uncanny taking place, something that transcends ordinary life, something that takes you out of time to a place that is hard to define. In fact, I am completely out of place.

This merging of the here and now with the there and then also takes in my own history watching East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause and Giant, wondering how a vital 24-year-old can suddenly be snuffed out in seconds. The astonishing fragility of life. Those seconds have taken on some sort of monumental quality, meaning that a pilgrimage of this sort is often trying to make sense of the meaninglessness of death, taking time to remember and mourn.

The miles pass and the roads are strewn with telegraph poles. Either side of the highway rise those dry, scrubby mountains. You see cars in the distance that seem to take an age to reach you. Everything is hazy in the heat.

The next stop is a telegraph pole on a flat road in a place called Wheeler Ridge. This marks the spot where Dean was pulled over for speeding. In this parallel world of pilgrimage you have to pull off the current road to find the old one, which is narrow and not quite dirt, but easily could be.

A dedicated fan has worked out where Dean was stopped and hammered into the pole the letters JDLD (James Dean Last Drive). It is one of the many “if only” moments. If only he had not been stopped for speeding, he would have cleared the junction at Cholame before Turnupseed arrived.

More miles pass through the odd lunar landscape, and straight roads run alongside occasional fields of oil derricks. The heat haze grows stronger as the afternoon boils to 117 degrees. There is no shade on these desert roads.

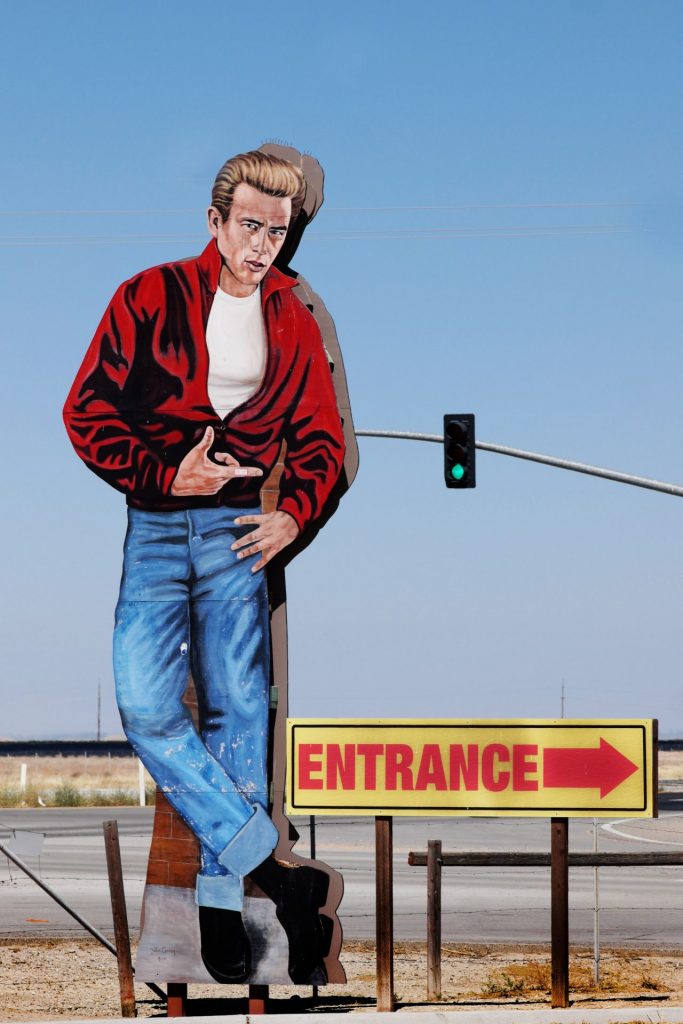

Next is Blackwell’s Corner. You cannot miss it for there is an enormous James Dean cutout sign with his finger pointing the way. He is wearing his red jacket from Rebel Without a Cause. Here, in the small gas station, he bought a Coca-Cola and an apple before his final push to Salinas. Now the place where Dean would have stopped has been knocked down and the existing petrol pumps cover the shack where he bought his snacks.

Blackwell’s Corner exists in affectionate remembrance to Dean. A sign on the door asks you to buy something to keep the place afloat and, frankly, it would be impossible not to buy anything. Inside is the Forever Young Diner with a mural featuring Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, John Steinbeck (who was born down the road) and some other people I couldn’t quite identify.

A model of Marilyn in her famous white dress sits flirtatiously at the diner’s counter. There is the East of Eden Fudge Counter and a large shelf full of bottles of James Dean Hot Sauce. At the back of the store, behind bullet-proof glass, is a pair of Dean’s orange driving goggles.

Suggested Reading

When will Quentin Tarantino shut the f*** up?

According to the information provided, they were swiped from the crash scene by a woman who initially tried to take a hub cap from the mangled Porsche until her husband told her that was unethical, so she took the goggles instead. Although this stop-off sounds exploitative, it isn’t. The whole place is done with taste and respect and knows it exists because of a chance moment in history where someone half an hour from their death stopped for an apple and a Coke.

From here it is a clear run, only about half an hour, to the crash site. Armed with my James Dean fridge magnet bought from Blackwell’s Corner, it is a moving experience driving those last minutes.

The road now is slightly different to the one Dean drove, but only just. He would have taken the old Route 466, which is metres away from the existing Route 46. At certain points you can see the old road, and I instruct my long-suffering companion to pull over so I can take a look at this ghostly track that emerges from the rubble.

At the top of the Antelope Pass the current road smoothly curves down to the fatal junction, but the old Route 466 waves and humps its way down. I uncover a dirt track bordered with dry scrub and piss off a startled rattlesnake as I follow the fragments of a 1950s road. Bits of tarmac appear from the earth until eventually spectral white lines emerge in the middle of the road and I can see it bumping its way down to the intersection.

The crash site itself is in the middle of nowhere. The road is busy but the fence, roughly where Dean’s car would have landed, is full of offerings – flags, underwear, beer cans, statues, cigarettes, rosary beads, pictures, notes, and now my fridge magnet.

The traffic whizzes by this melancholic celebration, those two seconds in 1955 that are anaesthetised in time. It is a place to stand and remember. It is a place for shedding time, where chronology is messed up, and the past flares to life, just for a moment. James Dean is dead but powerfully alive.

The drive back to LA is muted. Reversing the route should feel like reanimating Dean, but instead it feels like the drive that he should have taken but never did.

Stopping off in Sherman Oaks for pizza and wine, the night has turned chilly. The restaurant has an indoor fire pit behind glass. I reflect on the day and what has occurred, the boundaries of time and space that have been crossed, the remembrance, James Dean. The palm trees outside are flickering with neon and the lovely, darkening, magenta sky of a Los Angeles evening.

Dr Gail Crowther is the author of Dorothy Parker in Hollywood (2024) and Marilyn and Her Books: The Literary Life of Marilyn Monroe (forthcoming, 2026). Kevin Cummins’s latest book is Oasis: The Masterplan