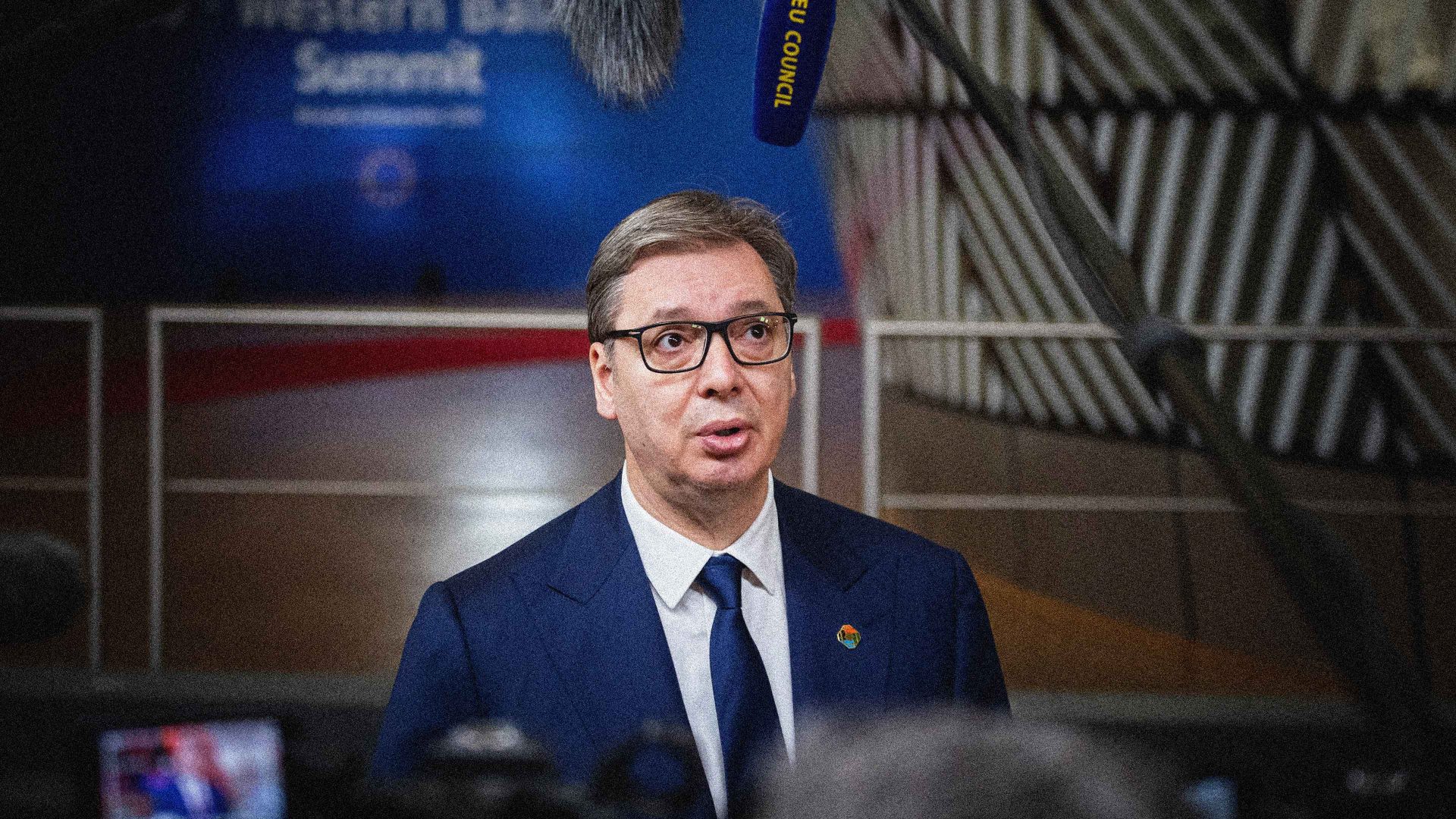

When president Aleksandar Vucic inaugurated a railway station in the Serbian city of Novi Sad in 2022, it was meant to signal his country’s move towards a brighter future. “This is our way to modern Europe – our way to a better, progressive Serbia,” he told the BBC.

In November of last year, just months after the station was completed, the concrete awning collapsed and killed 16 people. Student-led protests demanding justice that started in Novi Sad soon spread to the rest of the country, pulling in people from across society, with at times hundreds of thousands taking to the streets. Ten months on from the collapse, the protests are escalating.

Some demands have been met, including the resignation of the prime minister, Milos Vucevic, and some high profile arrests. Vucic, whose party has been in power since 2012, remains president. After experiencing years of corruption and the weakening of democratic institutions, Serbians want a reinstatement of the rule of law. But unlike in other recent European pro-democracy protests movements, such as in Georgia and Slovakia, many Serbs see the EU as part of the problem. Instead of being an antidote to the erosion of democratic freedoms, the EU has fuelled frustration – it is widely perceived as having been too apathetic or supportive of Vucic.

Brussels was slow to respond to the protests. It wasn’t until April, five months after they started, that the EU put out a proper statement supporting the protesters. Marta Kos, the European commissioner for enlargement, said the EU’s demands for democratic reforms in Serbia were very similar to the protesters. But apart from a smattering of comments the bloc has publicly taken a hands off approach to initiating change.

In the past, Serbian opposition politicians have accused the EU of ignoring democratic backsliding under Vucic, during whose presidency Serbia became a candidate for the EU, in exchange for security in the region. In October 2024, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, praised Vucic for his commitment to delivering reforms on the rule of law and democracy. A subsequent European Commission report found that political pressure on the judiciary was high and that, among other issues, there were increasing concerns for the safety of journalists.

“The EU missed a million opportunities to be more vocal about some issues, or to do more about them,” said Nikola Burazer, programme director at the Centre for Contemporary Politics. “If it really does care about enlargement, if it does really care about its own values being defended in this region, then it should have had different approaches to the situation in Serbia,” he said.

In August there were widespread reports of police brutality against protesters. David Slavkovic, 36, an editor at a music magazine, was filming someone being attacked by police when he was targeted. The assault left him with thick bruises on his back and a wound to the head. Slavkovic got involved in activism a few years ago after becoming frustrated with sewage leaking onto his street, a result of bad infrastructure due to corrupt local planning regulations.

Suggested Reading

Bring on the United States of Europe

“The canopy fall was just a tip of the iceberg of what’s happening,” he told me, referring to the Novi Sad disaster. “And that’s why we’re rebelling, not because we want to, it’s because nobody listens.”

Slavkovic has been frustrated with the EU’s “lukewarm” response to the protests. “It seems like they have more interest in just keeping this corrupt government in place,” he told me. The EU has done long term damage to its reputation and trust in Serbia is low. In Slavkovic’s view, that started with the bloc’s backing of Rio Tinto’s lithium mine in the Jadar Valley.

The EU sees the mining project as a crucial opportunity to source more of the crucial ingredient needed for lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles, at a time when China dominates the market for EVs. But locals are concerned about the project’s impact on the environment and agricultural communities, accusing Brussels of prioritising the EU’s needs over their own.

Florian Bieber, professor of politics and history at the University of Graz told me that the mining deal has fuelled a widespread perception inside Serbia that the EU treats the western Balkans as a colony. “There’s this traditional scepticism towards the west, which feeds into all of that,” he said.

Serbia’s tensions with Europe have roots in the 1999 Nato bombings, a response to ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. Frustration has been compounded by the fact that Kosovo, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008, is recognised by most EU states as being independent and is considered a potential candidate for EU membership. The eurozone crisis, the migrant crisis and Brexit have all added to skepticism about the EU’s capabilities.

Less than half the population in Serbia support joining the EU. Recent analysis of student protesters in Belgrade found that only 40% would vote to join the bloc, while a third were undecided. The researchers observed that after witnessing Brussels wade through crisis after crisis, the students, who are divided between liberals and conservatives two to one, doubt Brussels’s readiness to foster democracy in the region.

Student protester Anja Desopotovic, 25, told me that it is not a question of whether protesters support EU membership, because they are “under no illusion that Serbia is anywhere close to achieving it”. They are adamant the bloc is the only international actor who has the leverage to ensure a fair democratic process in Serbia, which is why they have been so “surprised and disappointed by the lack of concrete support from the EU”.

Vucic has claimed the protests are part of a foreign plot to overthrow his government. While he did not specify who he thought was behind the plot, Russia has hinted at western involvement. Foreign minister Sergey Lavrov warned western nations against supporting a colour revolution in Serbia, a reference to popular uprisings against former Soviet states. Moscow has continued its support for Vucic’s government.

According to Vuc Vuksanovic, senior researcher at Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, some protesters are more frustrated with Brussels than Moscow because Russia does not talk frequently about democracy and human rights in the same way the EU does. The EU is being judged on a different set of standards and Brussels’s hypocrisy frustrates people, he said.

Vucic may go. The EU’s ever growing list of tensions with Serbia will not disappear. Neither will Russia. For now Moscow is backing Vucic. But as was the case with former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic, Russia has a long history of backing allies to the bitter end and then when they finally fall quickly fostering relations with their successors. For the EU it’s hard to be optimistic. The bloc will need to do a lot to build trust in Serbia again. That will take years.

Frankie Vetch is a London based journalist. He covers European security, foreign policy and human rights