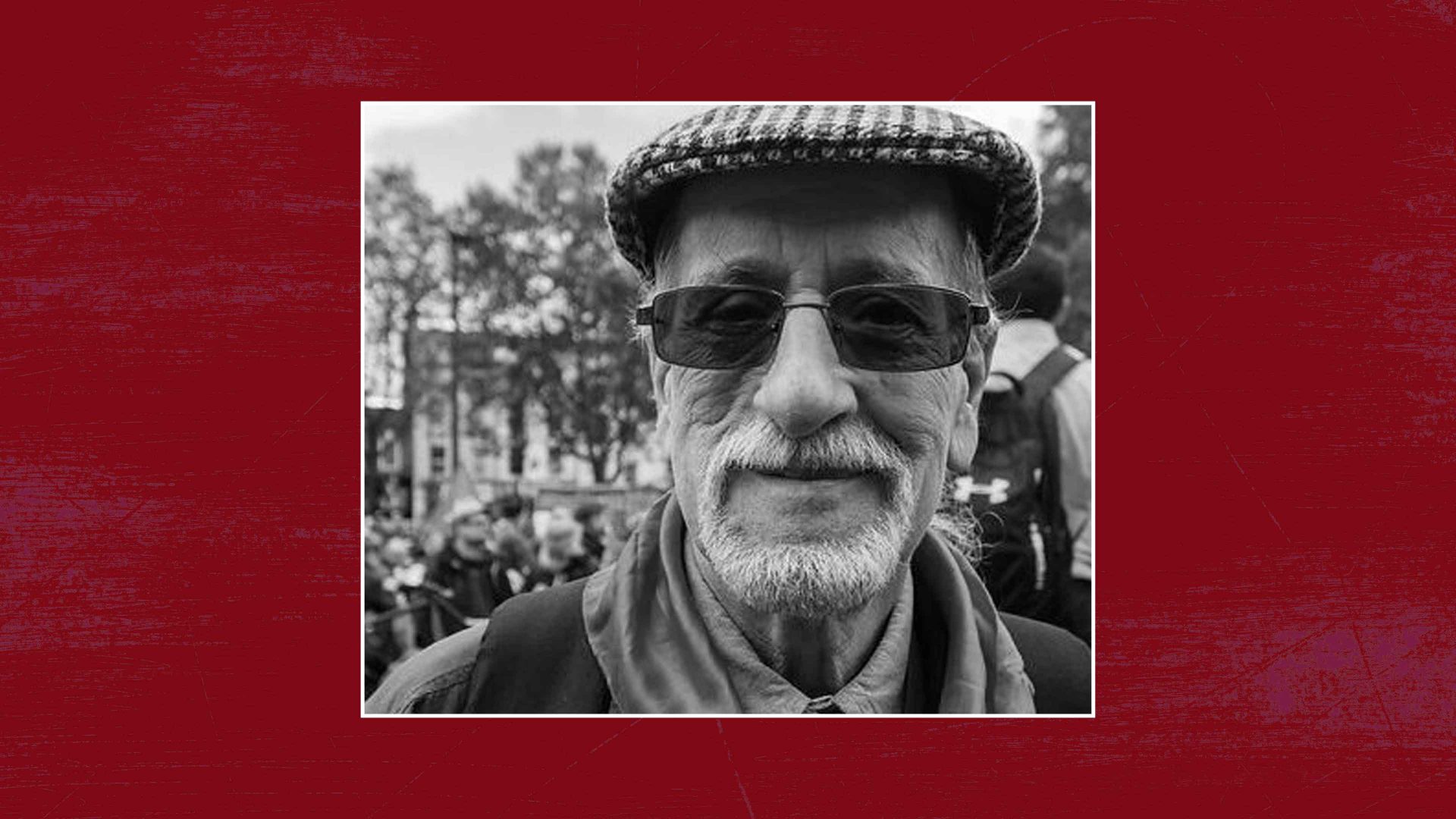

The anti-racism campaigner Gerry Gable died on January 3, but the evils he fought are more mainstream now than at any time since the war.

The first time I spoke to him, Gerry was doing something he did very seldom: apologising. It was 2015, and I was working on my biography of my father, an infamous inter-war fascist called John Beckett. My research took me to a dinner in a central London hotel, held by the Friends of Oswald Mosley. I wrote a long colour piece about it for the Independent on Sunday.

Gable’s anti-fascist paper Searchlight was also there, but undercover, and his reporter wrote a furious piece about my betrayal in reporting on fascists openly and with their knowledge. I felt I ought to have been asked for comment, and he agreed. He showed up to my book launch a few months later.

That conviction, that you spy on fascists, that you harass them, that you never just chat politely to them, ran through his whole life and work. Born in the East End of London in 1937 to a Jewish mother and an Anglican father, as a child he admired the 43 Group – a group of Jewish ex-servicemen set up in 1946 to stifle a resurgence of fascism and antisemitism, largely by breaking up meetings.

As a young man, he joined the Communist Party, eventually leaving it because it opposed Israel, though he remained on the left all his life. Those were the days when support for Israel came largely from the left, which viewed the country as a model of social democracy. The far right’s fervent embrace of Israel is more recent.

As a new wave of racism hit the streets in the 1960s, Gable helped found the 62 Group, largely modelled on the 43 Group, to prevent fascists and racists from organising. He gathered information for the group, and this led to the formation of the anti-fascist magazine Searchlight, with which Gable’s name will always be associated. It had a brief life in the mid-60s, but was relaunched in 1975, and is with us still.

It was, he wrote in his last article in March last year, “a response to the worrying growth of the National Front and a desire to put the intelligence-gathering expertise of the 62 Group at the service of the local anti-fascist groups which were springing up all over the country.”

The National Front was doing alarmingly well in local elections, and, wrote playwright David Edgar, Searchlight exposed “the openly Nazi (and criminal) pasts of the NF leaders, their links to more overt organisations, and – buoyed in confidence by their electoral successes – the Front’s increasingly open espousal of overtly Nazi ideas.”

Suggested Reading

The ex-Nazis who got away with their past

Gable believed he could not afford to be squeamish about his methods. Infiltrators and spies were on his books, and a little light burglary was all in a day’s work.

He was often right, but not always. He lost a libel case to Neil Hamilton and Gerald Howarth, costing the BBC £40,000, and Private Eye’s false allegation that a member of the military police had plotted to murder Gable cost the magazine “substantial” damages.

Few people would deny his courage, his determination, and his genuine loathing of racism. His methods, he would argue, were unlovely but necessary. As he wrote last year:

“The battle against right wing extremism must be fought on all fronts. Campaigning and demonstrating against them is vital but not sufficient. We also need to wage an intelligence war which informs us about their plans and crimes which we can use to disrupt their activities.”

But the world has changed. Today Tommy Robinson’s protection comes, not from a few like-minded thugs, but from the world’s richest man. Baseless claims that foreign migrants are eating the King’s swans come not from fanatics on street corners, but from a man who might be our next prime minister. The president of the United States routinely uses racist taunts.

Gerry Gable never confronted a world where fascism and racism were mainstream. I wonder what he would have made of it.

Francis Beckett is a playwright and biographer. His most recent play is Make England Great Again