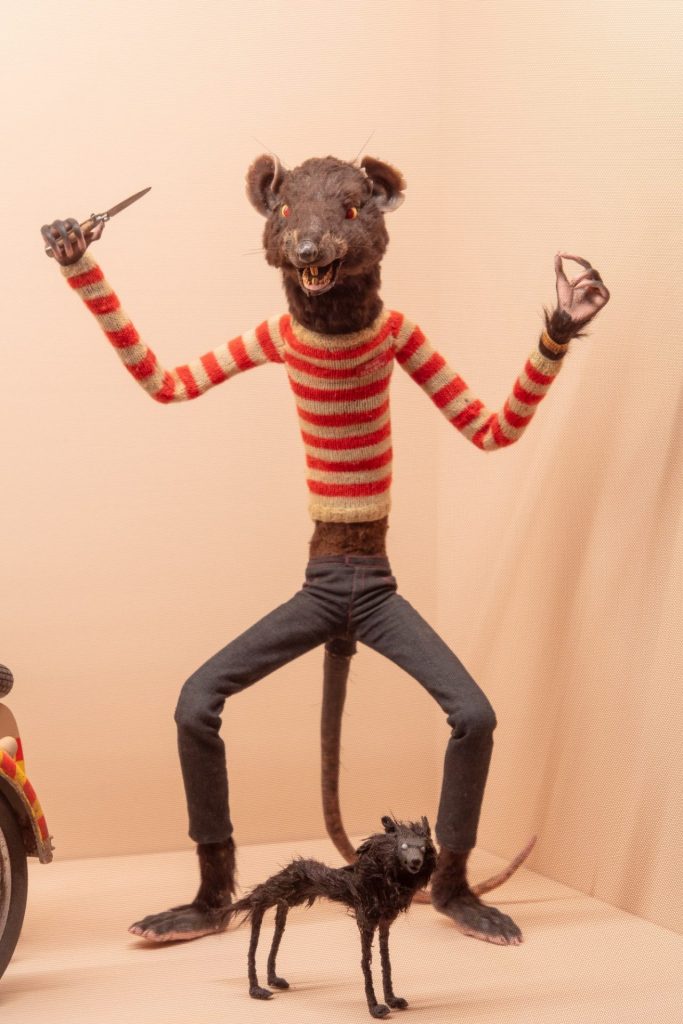

Of all the treasures in film-maker Wes Anderson’s archive – a choice selection of which is currently on show at the Design Museum in London – it’s the tiny sets and models for stop-motion masterpieces, including Fantastic Mr. Fox, that are its stand-out delights. Wondrously and meticulously detailed, and reproduced at multiple scales to allow for both close-ups and long shots, they represent a degree of artistic commitment to bring tears to the eyes.

Perhaps you’ve never stopped to wonder about Mr Fox’s brown corduroy suit – it’s by Savile Row tailor Scabal. Maybe you assumed that the family home in The Royal Tenenbaums was a set? Not a bit of it – the address is fictional enough, but 111 Archer Avenue was genuine New York bricks and mortar, decorated and furnished for

the film.

Such unpredictable blurring of real and imagined is one of the great pleasures of this retrospective exhibition, and the films that map a roughly chronological route through Anderson’s career.

Though heavily and unmistakably shaped by influences from French New Wave auteurs Jacques Demy and François Truffaut, to Belle Époque photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue, the films occupy worlds that are entirely Anderson’s own.

Reality intervenes in unlikely ways, but so does artifice: the impossibly vast pink façade of the Grand Budapest Hotel, which features only briefly in the eponymous film’s opening sequence, is in fact a miniature set, like the front of a particularly magnificent doll’s house.

“Whatever the scale, Anderson’s is a dollhouse world,” writes Glenn Adamson in the accompanying book. “He is especially attracted to environments where he can control all the action.”

The London exhibition, which runs until late July, is not the only place where Wesophiles can get their fill. At Bar Luce, the fully functioning cafe Anderson designed for the Fondazione Prada in Milan, the director’s influence is inevitably curtailed, though entering it is still very much like walking inside someone else’s imagination – and it seems quite likely that patrons become a bit more Wes Anderson with their caffè or Campari.

The tiny set of The Grand Budapest Hotel

But since Anderson’s way is to present reality with the volume turned up, Bar Luce, with its formica furniture, hard dark lines, and ice-cream colours, is never just a classic mid-20th century Milanese bar.

Anderson has said that he took a different approach to the bar than he would to a film set: he set out to create “a space for real life with numerous good spots for eating, drinking, talking, reading, etc. While I do think it would make a pretty good movie set, I think it would be an even better place to write a movie. I tried to make it a bar I would want to spend my own non-fictional afternoons in.”

It’s in Anderson’s “non-fictional afternoons” – the spaces in which his imagination roams beyond the very specific demands of his current screenplay – that the seeds of his enclosed, choreographed worlds are sown.

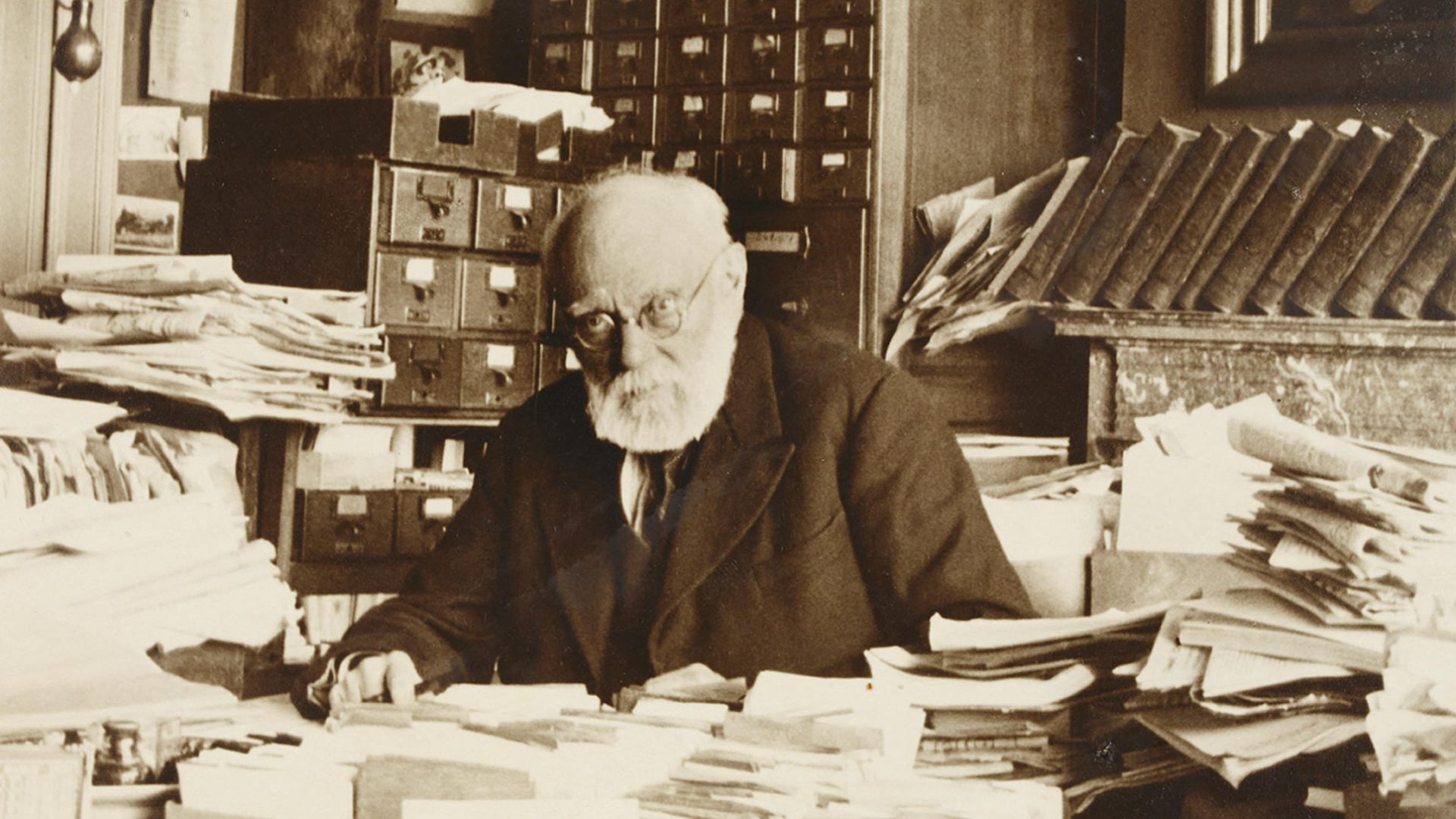

In Paris until March 14, you can see the kaleidoscope of Anderson’s visual worlds unfurling in the window of Gagosian gallery on the rue de Castiglione, where he has recreated the New York studio of the artist Joseph Cornell.

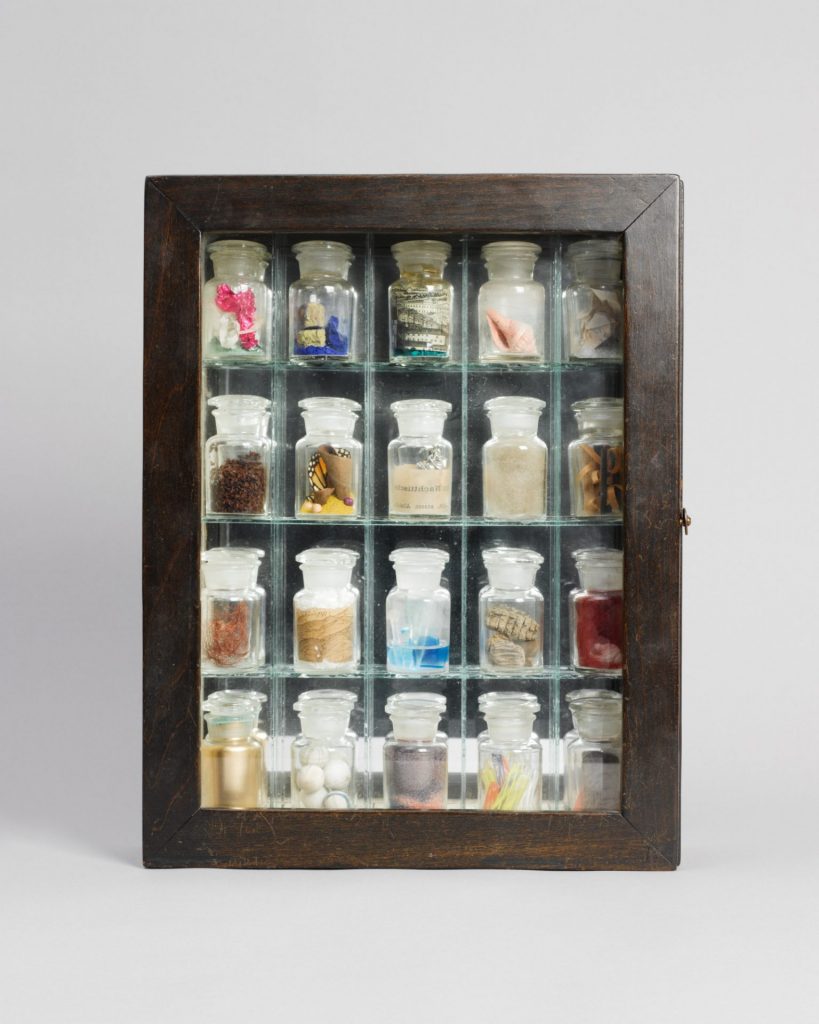

Cornell (1903-72) is famous for the miniature worlds he created inside glass-fronted boxes, made from materials gathered on his walks around Manhattan’s junk shops and book stores.

He lived with, and cared for, his mother and disabled brother in the family home in Flushing, Queen’s, on the wonderfully Andersonian Utopia Parkway. Here, in the basement, he made his studio, which fellow Cornell enthusiasts Anderson and curator Jasper Sharp have recreated in Paris, in a glass-fronted gallery space just like one of Cornell’s shadow boxes.

Anderson first discovered Cornell in the Menil Collection in Houston, where he grew up. The collection includes Palace (1943), its grand classical façade, viewed head-on inside its case, the very seed of the Grand Budapest Hotel. It’s not just the architecture that is strikingly similar, but the flat, head-on viewpoint that would become a distinguishing feature of Anderson’s films.

Suggested Reading

Mary Kelly’s countdown to catastrophe

When Sharp and Anderson installed The House on Utopia Parkway: Joseph Cornell’s Studio Re-Created by Wes Anderson (2025), it was Anderson who insisted on once again marrying his vision with Cornell’s, bringing the objects up to the glass to direct and contain the viewer’s gaze, just as Cornell does with his boxes, and Anderson does with his films.

The curious irony is that while Cornell and Anderson both exert such control over the experiences they create, they also find uncommon freedom in doing so. Writing in the Gagosian Quarterly, Sharp describes Cornell’s fascination with Paris, a city he never visited – he never left New York – but “dreamed of his entire life”.

Early on in his friendship with Marcel Duchamp, the pair talked of Paris, walking its streets together in their mind’s eye. “Only at the end of the conversation did Cornell mention that he had never in fact visited the city,” writes Sharp, “an admission that left Duchamp speechless.”

Anderson’s exhibition at the Design Museum is full of souvenirs from the many places he has visited in his films, and thus his dreams. Here, displayed for us to look at, the Issue-in-Progress Board from The French Dispatch, and even the identical yellow spiral-bound notebooks in which each film is conceived, are an echo of Cornell’s shadow boxes, seeds waiting to be sown in a new generation of creative minds.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is at The Design Museum, London until July 26. The House on Utopia Parkway: Joseph Cornell’s Studio Re-Created by Wes Anderson is at the Gagosian, Paris until March 14