In 1908, there were so many Australian women artists in London that they got their own exhibition, staged as part of the Franco-British Exhibition to celebrate the signing of the Entente Cordiale four years earlier. Awards were given, with “Miss Thea Proctor and Miss Frances Hodgkins equal for the first award, valued at £50, and these ladies divide the first and second awards between them.”

Proctor and Hodgkins are among the best known of the 50 artists featured in Dangerously Modern, a major exhibition opening at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney on October 11, having debuted earlier this year at the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide.

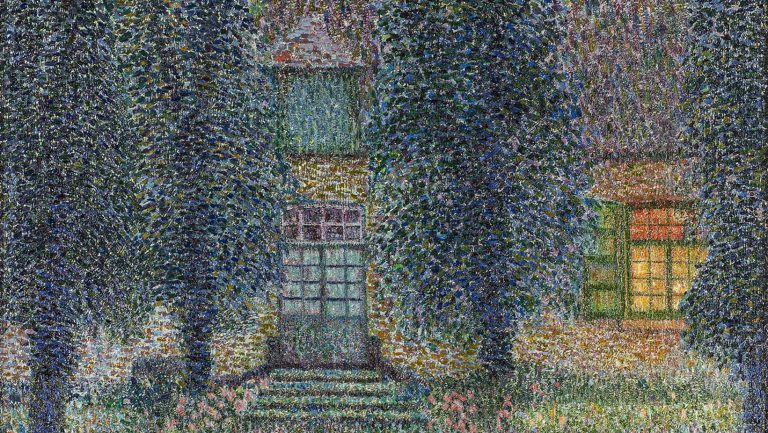

The exhibition spans the half-century between 1890 and 1940 through around 200 pieces of art, from paintings and sculpture to ceramics and textiles, exploring the lives and work of artists – many of them barely known today – who were a significant strand in modernism’s global story, with many of them duly recognised in their lifetimes.

Frances Hodgkins (1869-1947) is one of several New Zealanders included, often with little differentiation between the two nationalities, a decision, write curators Elle Freak, and Tracey Lock, of the Art Gallery of South Australia, and Wayne Tunnicliffe, of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, that recognises “these artists’ interconnectedness with those from Australia through friendship, teaching and travel, and the shared colonial histories of the two Australasian countries”.

The exhibition’s title was coined by Thea Proctor (1879-1966) who on returning to Sydney after the first world war, wrote that in Australia, her work was considered “dangerously modern.” This outsider status was intractable, because in London, and Paris they were similarly out on a limb – “nobody’s darlings”, according to a Melbourne newspaper report, marked out as different by their colonial roots and ways.

Still, the “call of Europe” was irresistible, and particularly to women: at the turn of the 20th century, Australian and New Zealand women in London significantly outnumbered men. They weren’t only artists, but for those with ambitions in that vein, the promise of life at the beating heart of the art world was irresistible.

This was especially true of Paris, not only “the nerve-centre of the arts, but the happy meeting-place of all those questioning foreigners who had succeeded in throwing off the shackles and prejudices of their home towns and had not yet wearied of an aimless freedom,” reflected the painter and writer Stella Bowen (1893-1947), in 1941.

Women made up a consistently high proportion of the Australian artists participating in the Paris Salons in the decades before the second world war. Though Bowen makes much of the freedoms enjoyed there; getting to Europe in the first place must have required considerable independence and resilience.

These were characteristics fostered by their experiences as settlers, says curator Wayne Tunnicliffe. “Women had often participated side by side with men in establishing themselves here, so there were freedoms in colonial society you didn’t necessarily have in London or France during that period”, he explains.

Suggested Reading

Helene Kröller-Müller, the heiress who bought the future

Consequently, women travelling to Europe from the southern hemisphere would have encountered unfamiliar curbs on their freedom: European women were still denied the right to vote decades after their South Australian and New Zealand sisters, who were granted suffrage in 1894 and 1893 respectively, though crucially, this was restricted to women of European descent.

Though women in Australia had opportunities to train as artists, and sometimes to exhibit their work, the art scene was nothing like those of Paris or London. In the late 19th century, it was dominated by the creation of the national identity, a thoroughly masculine endeavour typified by Tom Roberts’s A Break Away!, 1891, now in the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), in which an Impressionist style projects a distinctive image of a resourceful, hard-working population shaped by its intimate connection to the land.

“The women were not really participating in that national landscape tradition,” says Tunnicliffe. “There are women landscape painters, but they tend to paint more intimate themes, populated by women and children, rather than images of masculine labour in the landscape, which was the dominant Australian mode.”

Partly because they didn’t fit readily into European class structures, Australasian women were especially well placed to reimagine their identities and work. The British artist John Piper implied as much in his praise of Frances Hodgkins, whose identity as an artist was what defined her. She had, he said, “no parish, country, climate or anything else attached to her. She was just herself.”

Agnes Goodsir (1864-1939) explores similar ideas in Girl with Cigarette, 1925, whose self-confidence is wholly modern and projects intellectual as well as sexual freedom. “In Paris… art is something more than a polite hobby… it is an absorbing life work for many, and to many more it is the subject near their hearts and one that is discussed everywhere.” she told Adelaide’s the Advertiser.

Even so, domestic subjects from still life to interiors, to intimate female nudes feature heavily in the work of these artists, from Gladys Reynell’s Pensiveness, c.1913, to Alison Rehfisch’s Oranges and Lemons, c.1934, a painting that acknowledges Cézanne while prioritising design and geometry.

Just as surprising is the vivid colour that characterises so much of the work by Australasian painters, but that often only emerged after they had been to Europe, where encounters with the work of Matisse and Van Gogh made a permanent impact on the work of Grace Cossington Smith (1892-1984) for example.

Many artists stayed put, Frances Hodgkins in Britain, where she died in 1947, and Agnes Goodsir in Paris, where she died in 1939. Cossington Smith was among the many who returned home, where the effects of her time in Paris and London emerged gradually, and in response to the artistic environment of Sydney, so that – though inflected with the vibrant colour combinations of Van Gogh and the Fauves – her paintings are in a category of their own.

Grace Crowley’s 1930 portrait of Miss Gwen Ridley is similarly elusive, painted, in a style that the curators note, “could have been painted in any studio around the world”. It’s this that was judged to be so “dangerously modern”: unlike their male counterparts, occupied with the creation of a new nation, these pioneering women were erasing traditional measures of identity and belonging, that had as much to do with gender as with geography.

Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890-1940 is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney until February 1, 2026