She was one of the most daring, subversive and distinctive photographers of the 20th century. A creative dynamo with a tricksy, surrealist eye; a photojournalist who documented the horrors of the Nazi death camps of Dachau and Buchenwald; the creator of an idiosyncratic record of the people, places and events that shaped her lifetime.

Tate Britain’s retrospective is the biggest exhibition dedicated to Lee Miller ever staged in this country, and brings together well over 200 vintage and modern prints, from early collaborations with Man Ray to the equally surrealist fashion shoots for Vogue in the early years of the second world war. Shortages of everything – apart from hats, which were not rationed – demanded all her talents for fun and invention, and in one shot, never published, she finds glamour in the bombed ruins of London’s Middle Temple.

The extraordinary, deeply unsettling image of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, made with the assistance of her colleague David Scherman after the seizure of the Munich apartment by the US Army, is now more famous than ever following Kate Winslet’s turn as the war-hardened correspondent in the 2023 film Lee. In another of Miller’s better-known, and characteristically mischievous war pictures, it’s the ever-helpful Scherman again, posing in his gas mask with his camera.

Miller created quantities of photographs that are genuinely worthy of the description “iconic”, and yet the number of lesser-known pictures, some of which are on display here for the first time, is a reminder that the Lee Miller Archive is an immense, ongoing project.

In his 1985 biography of Miller, the photographer’s son Anthony Penrose reintroduced the world to a more or less forgotten figure. Traumatised by the war, and her rape at the age of seven, Miller’s final 20 years were plagued by depression and alcoholism.

“Her disparagement of her own achievements was so intense that everyone was convinced that she had done little or no work of significance,” wrote Penrose. It was only after her death in 1977 that he began to piece together the truth about his distant, difficult mother, from the negatives and prints he found abandoned around her East Sussex home.

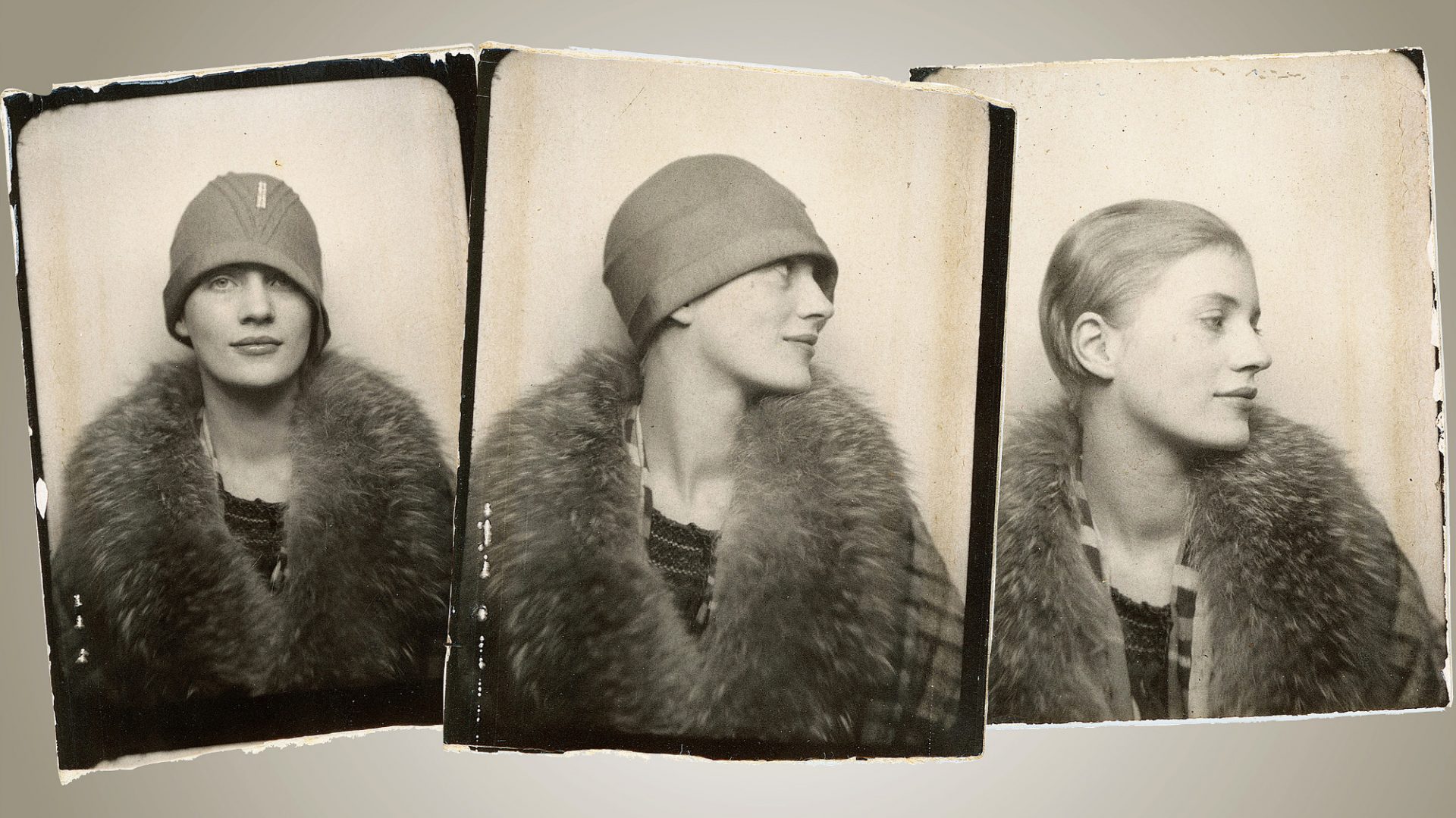

On show for the first time is a photobooth strip, that, taken in 1927, soon after the invention of Photomaton booths in 1925, is Miller’s earliest known self-portrait. Her love of new technologies was lifelong, and in the 1940s she experimented with colour, studying technicolour films at the cinema to understand, she explained, “what these millionaire film companies have learned the hard way about it all.”

She shot her first colour cover for British Vogue (Brogue, as it was nicknamed), in April 1944, which is here as part of a colour-saturated display entirely at odds with the monochrome gloom that pervades the wartorn London of the popular imagination.

A trove of pictures taken during the five years Miller spent in Cairo before the war makes sense of a period often understood as a hiatus, when her marriage to the Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey installed her in a life of idle luxury at the heart of the city’s “black satin and pearls set”.

Miller had been running a commercial studio in New York when she met, and soon after married, Eloui in the summer of 1934, throwing it all up to start afresh in Cairo, just as Vanity Fair recognised her as one of “the most distinguished living photographers”. It was a characteristically risky move, writes Penrose: “She wanted to take pictures and to travel, and being born neither rich nor a man she could achieve this only through others, such as Aziz.”

Still, according to the exhibition’s co-curator, Saskia Flower, “Miller had renounced photography on leaving New York,” her interest revived by a trip to Jerusalem which was followed by frequent trips into the desert, made with friends, among them the writer and poet Robin Fedden, and Bernard Burrows, then an official at the British Embassy in Cairo, and with whom Miller undertook a 900-mile tour of Egypt’s western desert.

Freed from the commercial constraints of a studio, Miller could take the pictures she wanted, and she pursued her fascination with the desert landscape, and sunlight of such ferocious intensity that her reflection could be caught in a dusty hubcap. The strangeness of the desert suited her surrealist imagination: bleached snail shells cling like fossilised berries to the desiccated branches of a desert shrub; shadows falling across the Colossus of Ramesses II, at Memphis, Egypt, give the semblance of life, even of sensuality, to this evidently lifeless, ancient sculpture.

Ultimately, Miller’s desert adventures were not enough to distract her from a life to which she was hopelessly ill-suited, and in the summer of 1937 she escaped to Europe where in Paris, Cornwall and the south of France, she was reunited with her surrealist friends including Picasso, Man Ray and Eileen Agar. It was on this trip that she met the British artist and curator Roland Penrose, who would later become her second husband.

Suggested Reading

A tragic radical’s search for meaning

Made in 1937, after her return to Egypt, Portrait of Space is Miller’s best-known photograph from this period. An extended meditation on space and enclosure, freedom and constraint, it is often interpreted as a cry of longing for Europe and her new love, anticipating her final split with Eloui in 1939, when she returned to Europe at the beginning of the war.

Seen here alongside so many other desert pictures, it can no longer be understood as the rekindling of a long extinguished flame, though its sophistication and artistic intent remain clear.

In the summer of 1938, Miller and Penrose travelled again through a Romania apparently untouched by the 20th century. Despite its unrelenting rusticity, Miller imbues it with strangeness, finding surreal elements in a pile of shoes made from old car tyres, or the head of a slaughtered cow in a cart.

Miller returned to Romania, in the aftermath of Hitler’s defeat, on a desperate tour of Europe that was principally an exercise in delaying the inevitable, anticlimactic return to peacetime and normal life. But first, there was the war.

Lee Miller is at Tate Britain until February 15