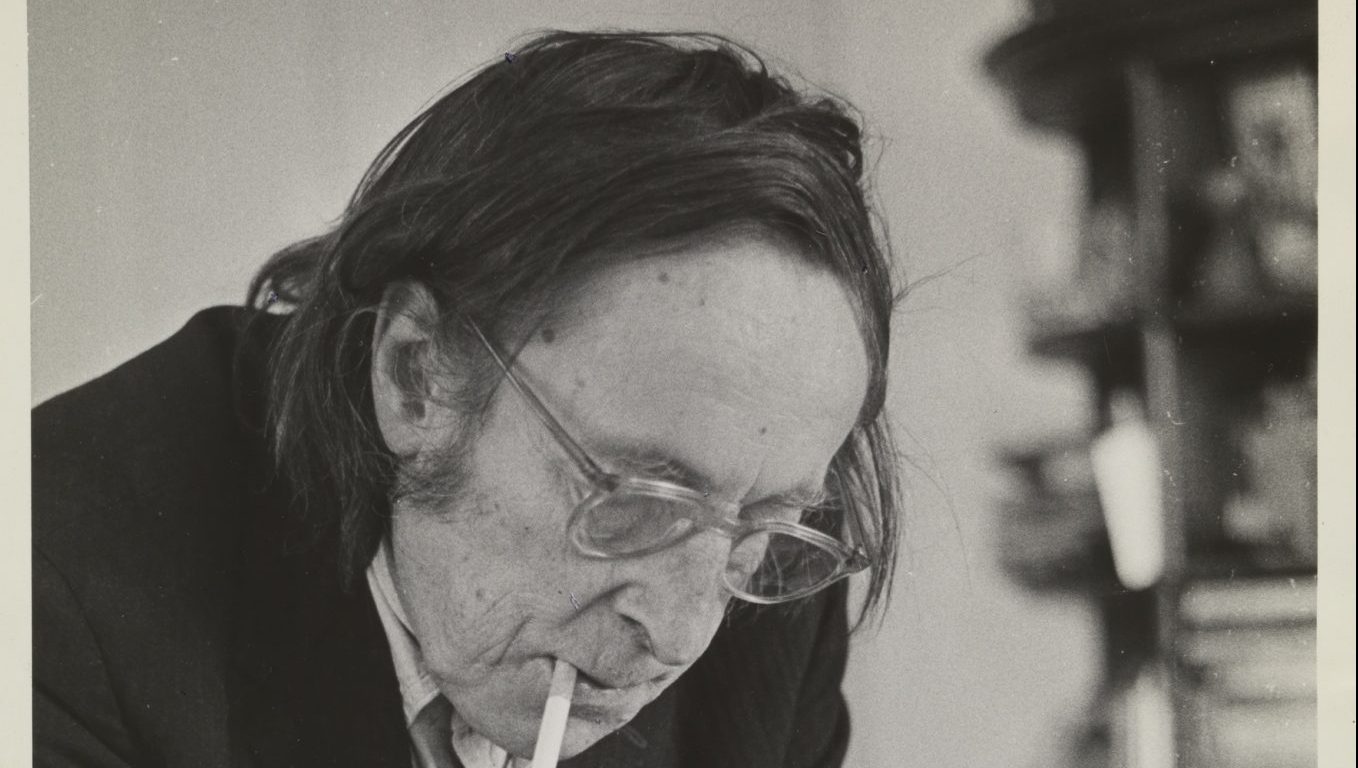

“I never tell anyone anything… I don’t see that it matters.” There’s a reason the English painter Edward Burra (1905-1976) has remained an enigmatic figure, despite the filmed interview that elicited this particularly gnarly response in 1972, four years before his death.

Commissioned by the Arts Council, the interview coincided with the Tate Gallery’s 1973 Edward Burra retrospective, which, according to the artist’s friend, the photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer, he attended grudgingly, walking through “almost without pausing or appearing to look right or left… saying as he left ‘very nice’”.

Now, Tate Britain has staged the most comprehensive exhibition to date, a thrilling immersion in the dark corners and sinister back alleys of the 20th century. From cities gripped in the ecstatic hedonism of the 1920s and 1930s, in Harlem jazz bars, and Paris nightclubs, to surreal, nightmarish imaginings of wartorn Europe, to the landscapes of postwar Britain, Burra’s paintings are simultaneously unique and familiar.

Burra painted Marseille and Toulon long before he ever visited them, peopling his French Scene of 1925-6 with friends and family. These imaginative flights were a respite from crippling rheumatoid arthritis, complicated by an inherited form of anaemia. His formal education ended at the age of 12 when he was sent home from boarding school following a bout of pneumonia, after which his education was largely his own business.

Painting became a necessity: “The only time I don’t feel any pain is when I’m working. I become completely unaware,” he said. It wasn’t all work. He loved music, drinking, and the raucous, seamy nightlife that was the refuge of the marginalised, from queers to crooks.

At home in his astonishingly untidy room at Springfield Lodge, the large, comfortable house where he lived with his parents, jazz on the gramophone, Burra could conjure up a night in a club, filling a sheet with vividly remembered details, recalled without reference to notes or sketches.

He lived at the house in Playden, near Rye in East Sussex, until 1953, when he moved with his parents into Rye itself, a place he disdainfully tagged as “Tinkerbelle Towne”, “a morgue” that he compared to “a kind of overblown gifte shoppe”.

The thrill of New York, and countless other new places, is conveyed in paintings from the 1920s and 1930s. You can easily become lost among the curious customers in his painting Minuit Chanson, 1931. Typical of Burra’s style is his use of watercolour to achieve subtly graded, opaque tonalities, and graphic blocks of colour, and there is a hint of the surreal in the dancing doll seen over the shoulder of the Black man in the foreground, and the white-framed spectacles that give a googly-eyed appearance to the bowler-hatted man on the left.

Suggested Reading

Hear the paintings sing: the art of Emily Kam Kngwarray

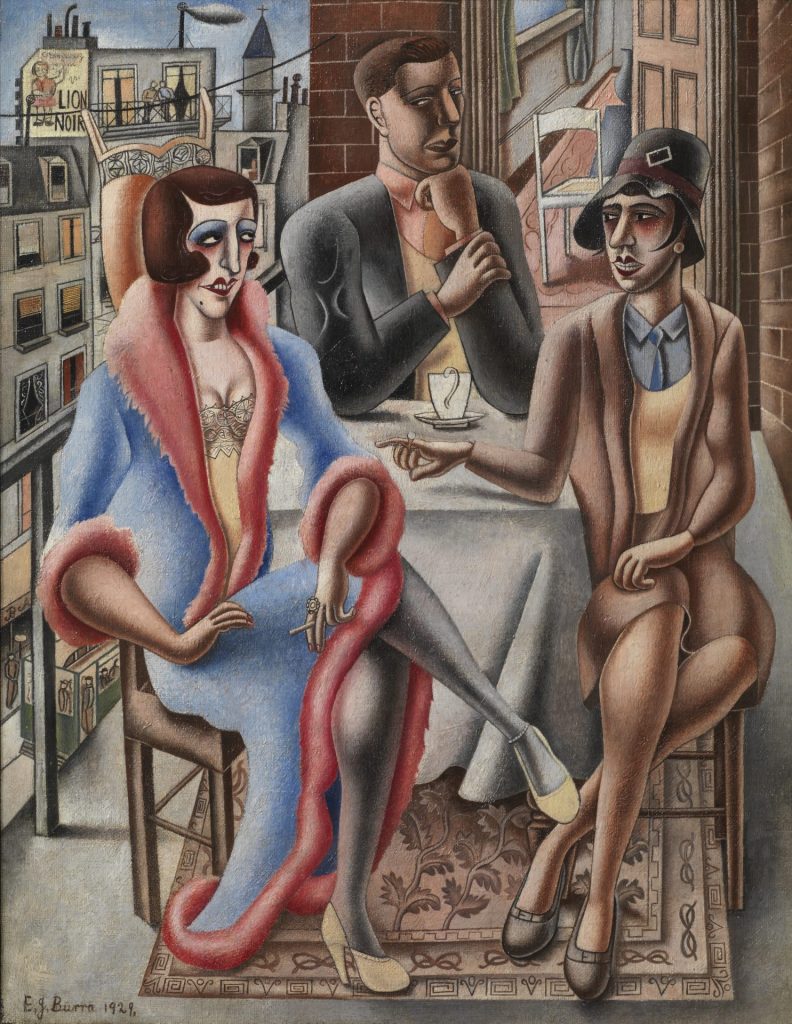

The boundary between fantasy and memory is blurred still further in The Tea-Shop, 1929. Though its title evokes the kind of genteel establishment familiar in Rye, the goings-on belong more to the Folies-Bergère, where Burra had seen Josephine Baker and others perform. Sitting at tables waited on by naked dancers are a bizarre collection of customers, one of whom is having tea poured over her head.

If Burra’s camp aesthetics and humour, and his fondness for sailors in tight trousers, suggest that he was gay, his sexuality is entirely mysterious, and according to his biographer Jane Stevenson, he claimed that his only erection occurred while watching Mae West.

Burra’s passion for Spain began long before his first visit in 1933. The grotesque and surreal character of stereotypical Spanish culture appealed to him, and bullfighting and flamenco, as well as the grandmotherly figure of the duenna feature heavily in his work, which would later include stage designs for Bizet’s opera Carmen, and the ballets Don Juan and Don Quixote.

In contrast to the Republican sympathies of most artists and writers, Burra claimed to support Franco, a position that seems more in line with his contrarian nature than any genuine fascist sympathies. In any case, his shock and distress are clear in comments he made in 1942 to John Rothenstein, then director of the Tate Gallery: “It was terrifying”, he said. “Constant strikes, churches on fire, and pent-up hatred everywhere. Everyone knew that something appalling was about to happen.”

The paintings that followed in the late 1930s were of an entirely new character to the bitchy social satires. In Bal des Pendus, (Ball of the Hanged Men) 1937, anonymous figures in hoods and carnival masks swing from a scaffold, overseen by a leering Beelzebub. High up on a rampart, faceless figures look on. It’s a horrible, sinister image drenched in paranoia and violence, and draws on surrealist cityscapes to convey the discombobulating horror of a war in which once familiar, even beloved people, streets and landscapes become estranged and distorted by violence and distrust.

The size of these pictures is striking, and show Burra’s refusal to be limited by the conventions of watercolour, a medium that he favoured in large part because it allowed him to work comfortably at a table.

Burra’s paintings become less populated later on, but he never lost his wicked humour. Burra relishes his soldiers’ muscled physiques, just as in Picking a Quarrel, 1968-9, the trucks and diggers carving up the English landscape might be caught up in a pub brawl.

Burra himself was increasingly frail as he got older, and relied on his sister to drive him around; there are fewer people in these unfolding landscapes, but their immersive character is as absorbing as the heaving bars and clubs of his youth.

The Edward Burra exhibition runs at Tate Britain until October 19, 2025